Energy Development in the Arctic

The Arctic has been an area of great global interest for oil and gas development. However, offshore oil and gas activities in the Arctic present risks to marine mammals and to the Alaska Native communities that depend on them for subsistence and cultural purposes. Those risks come from, among other things, sound generated by seismic surveys, drilling operations, and vessel and aircraft support activities; contamination from drilling and oil spills; and disruption of bottom habitats from temporary or permanent mooring or pipe-laying activities. The greatest risk to marine mammals and the marine environment is from oil spills, whether from drilling or ship-related accidents. Difficulties of responding to and cleaning up a major spill are heightened by the Arctic’s remoteness, harsh conditions, and relative lack of infrastructure, trained personnel, and response equipment.

Hypothetical oil platform in the Arctic Ocean. (Shutterstock)

What the Commission Is Doing

The Commission regularly reviews and comments on the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s (BOEM) proposed oil and gas leasing and development activities in the Arctic and on proposed Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) incidental take authorizations issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) for oil and gas exploration, construction, and operations. We also comment on and promote environmental studies to better understand the potential effects of oil and gas activities on Arctic marine mammals, and facilitate efforts to identify and address priority information needs through convening of workshops and meetings.

The Commission has commented specifically on the need for better information on the long-term and cumulative effects of oil and gas exploration, particularly exposure to sound from seismic surveys, drilling, and other activities; whether bowhead whales and other marine mammals are showing signs of habituation to sound; and whether animals are altering migration routes and foraging patterns to avoid exposure to sound-related disturbance or in response to changing climate conditions. Also needed is the continued incorporation of Indigenous Knowledge in assessments of distribution, seasonal movements, behavior, and health of marine mammals as well as subsistence use patterns. Such information is critical for federal and state agency decision-making processes.

U.S. Arctic Leasing Activities, 2012 to Present

BOEM’s 2012-2017 five-year leasing program had two lease sales scheduled in the U.S. Arctic—one in the Chukchi Sea in 2016 and one in the Beaufort Sea in 2017. The Commission submitted comments to BOEM on each of the two proposed lease sales (see letters section below). In October 2015, the Department of the Interior cancelled both lease sales citing market conditions and low industry interest.

In January 2015, President Barack Obama withdrew large portions of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas from new offshore oil and gas drilling, under authority of Section 12(a) of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act. In December 2016, the President signed Executive Order 13754 on Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience, which excluded from oil and gas leasing portions of the Bering Sea planning areas (the Norton Basin Planning Area and lease blocks within the St. Matthew-Hall Planning Area lying with 25 nautical miles of St. Lawrence Island). That same month, the President expanded the 2015 withdrawal to include nearly all of the Chukchi and Beaufort Sea planning areas. The 2017-2022 leasing program was approved in January 2017 and did not include any lease sales in the Arctic, consistent with President Obama’s directive.

In April 2017, President Donald Trump issued an Executive Order directing the Secretary of the Interior to consider revising the schedule of oil and gas lease sales for 2017-2022 to include those areas within the Beaufort and Chukchi Sea that had been previously withdrawn from leasing, among other directives. BOEM subsequently initiated the development of a new five-year National OCS oil and gas leasing program for 2019-2024 that considered leasing in all but one of the Alaska planning areas. That program was never implemented due to litigation.

On 20 January 2021, President Joseph Biden signed Executive Order 13990 reinstating Executive Order 13754 on Northern Bering Sea Climate Resilience and the 20 December 2016 Presidential Memorandum, which restored the withdrawal of the Chukchi Sea, portions of the Beaufort Sea, and portions of the Bering Sea from oil and gas leasing. In the Executive Order, the President also called for a temporary moratorium on all Federal activities related to the implementation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program in order to conduct a review, and as appropriate, a new comprehensive analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the oil and gas program. That review was initiated in June 2021 by DOI Secretarial Order 3401. In November 2024, BOEM released a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to the 2019 Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program EIS to provide a comprehensive analysis of the potential environmental impacts of the program, including addressing the deficiencies identified in Secretary’s Order 3401.

More information regarding oil and gas leasing on the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf, as well as links to relevant Commission comment letters, can be found on the Commission’s Oil and Gas Development and Marine Mammals webpage.

Exploration and Development of Oil and Gas Resources in U.S. Arctic Waters

Oil and gas exploration activities in the Arctic substantially increased in the early 2000’s. Interest was spurred in part by estimates of significant reserves in offshore waters of the U.S. Arctic Outer Continental Shelf (OCS). BOEM estimates of undiscovered technically recoverable resources of oil and gas in the Arctic in 2021 underscore the significance of the U.S. Arctic for potential oil and gas development, with 35 percent of the total U.S. potential offshore oil and gas resources contained in Arctic planning areas (27 percent in the Chukchi Sea and 8 percent in the Beaufort Sea).

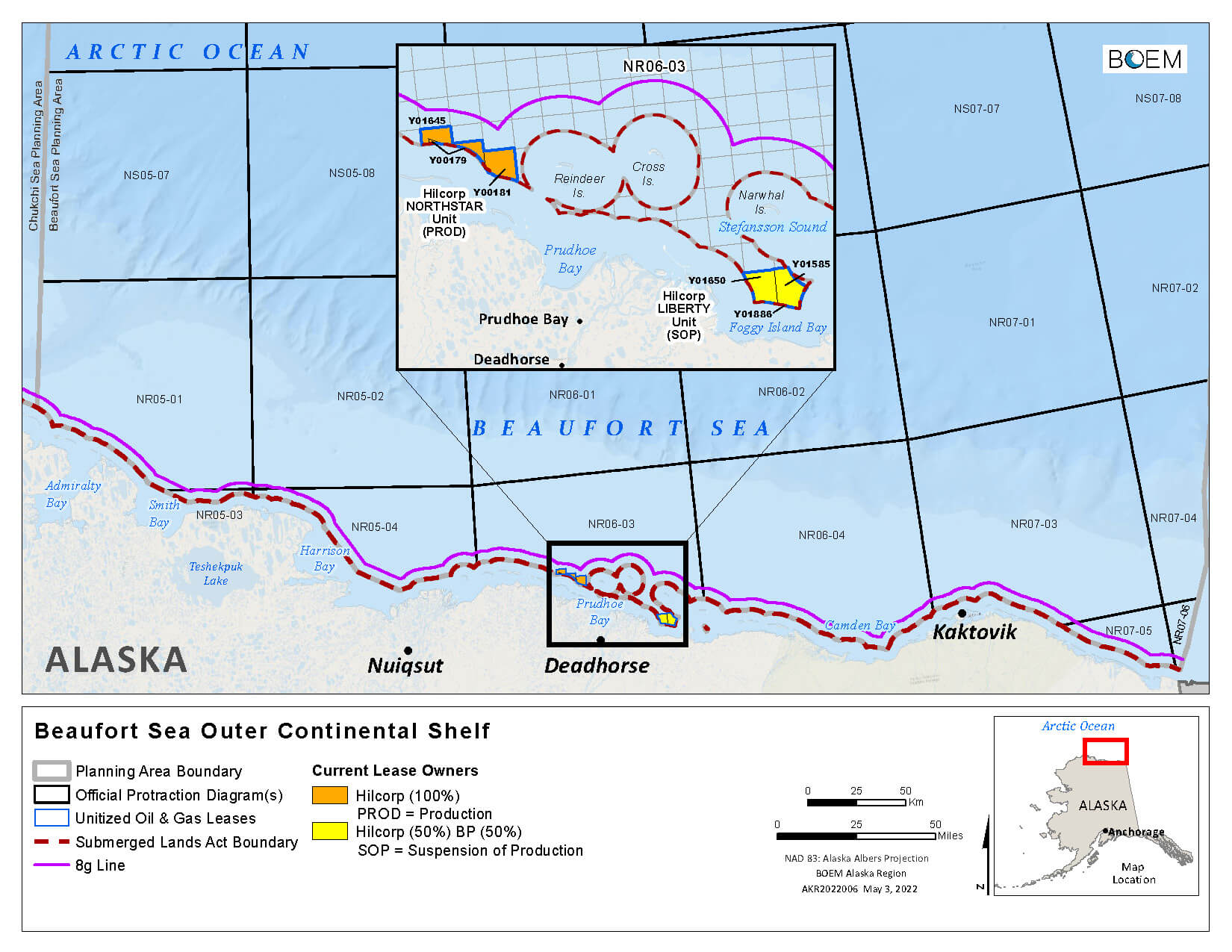

Map of active leases in the Beaufort Sea, Alaska, as of May 2022. (BOEM)

Exploration activities in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas since the most recent Arctic lease sale in 2008 have included seismic surveys, shallow hazards site surveys, and limited exploratory drilling. In 2012, Shell attempted to drill exploratory wells in both the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas, but was unsuccessful. In 2015, Shell drilled an exploratory well in the Chukchi Sea but failed to find any meaningful quantities of oil or natural gas. Shell subsequently announced that it would halt exploration efforts in the Arctic. All remaining leases in the Chukchi Sea have since been relinquished by Shell and others.

In July 2017, BOEM approved plans for Eni US Operating Co. Inc. to conduct exploratory drilling in federal waters from its Spy Island drill site, an existing man-made island in Alaska state waters. The drill site is north of the Nikaitchuq oil field, about three miles off Oliktok Point, in the Beaufort Sea. In April 2018, BOEM approved a revision to Eni’s exploration plan that allowed for drilling in Summer 2018. Eni initiated drilling a well at Nikaitchuq North in 2018 but suspended drilling operations in April 2019. BOEM has since notified Eni that its leases in Harrison Bay have expired.

Production drilling in U.S. Arctic federal waters is currently limited to the Northstar facility in the Beaufort Sea, which began producing in 2001. Northstar is a joint federal/state of Alaska project originally operated by BP Exploration Alaska Inc., but now operated by Hilcorp Alaska LLC. It is located about 12 miles northwest of Prudhoe Bay.

A new offshore production facility was approved for construction in 2018 at Hilcorp Alaska LLC’s Liberty oil field, also in the Beaufort Sea. BOEM finalized its Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) analyzing the potential impacts of Liberty’s Development and Production Plan in August 2018. However, a legal challenge to stop the project was approved by the Ninth Circuit in December 2020, citing BOEM’s failure to quantify emissions resulting from foreign oil consumption in its EIS and the Fish and Wildlife Service’s failure to account for non-lethal takes of polar bears in its ESA biological opinion. Hilcorp is currently updating its Oil Spill Response Plan for Liberty, which, once approved, would likely result in Liberty amending its Development and Production Plan. BOEM would then be obligated to prepare a new or supplemental EIS to reflect Liberty’s changes to the plan and to address shortcomings in the original EIS.

In July 2016, the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE) and BOEM issued a final rule governing exploratory drilling activities on the U.S. Arctic Outer Continental Shelf. The regulations were intended to ensure that exploratory drilling activities in the Arctic Ocean are conducted in a safe and responsible manner, while protecting marine, coastal, and human environments, and Alaska Natives’ cultural traditions and access to subsistence resources. In December 2020, BSEE proposed revisions to weaken the 2016 Arctic drilling rule, but the proposed revisions were withdrawn in June 2021.

Seismic surveys and drilling activities have the potential to harm marine mammals. Learn more about stages of oil and gas development and potential impacts to marine mammals.

Impacts of Oil and Gas Exploration on Alaska Native Subsistence

Oil and gas exploration in the Arctic (i.e., seismic surveys and drilling) has the potential to affect the availability of marine mammals to Alaska Natives for subsistence. Section 101(b) of the MMPA provides for the taking (harvest) of marine mammals “by any Indian, Aleut, or Eskimo who resides in Alaska and who dwells on the coast of the North Pacific Ocean or the Arctic Ocean if such taking is for subsistence purposes or for the purpose of creating and selling authentic native articles of handicrafts and clothing”, and “is not accomplished in a wasteful manner.”

Oil and gas exploration in the Arctic has the potential to significantly disrupt Alaska Native subsistence practices. Unless effectively managed, exploration activities, including drilling and seismic surveys, can directly interfere with hunting activities or disturb marine mammals through increased human presence and noise. The increased vessel traffic associated with these operations raises the risk of ship strikes, oil spills, and other forms of pollution, all of which pose threats to the health of marine mammals hunted for subsistence.

The Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission have jointly entered into annual Conflict Avoidance Agreements (CAAs) with oil and gas companies and seismic operators to minimize disturbance of the spring and fall bowhead whale subsistence hunts. The agreements specify areas and times that industry must not operate so as to avoid disturbing marine mammals before a hunt. The agreements also require the use of village-based communication centers to relay information between hunters and industry regarding planned operations and marine mammal presence and movements. The CAAs have generally been considered successful in minimizing impacts on subsistence activities, and hunters have recommended that future agreements be expanded to include other species besides bowhead whales and also to address other potentially harmful activities, such as shipping and fishing. They noted the agreements must also be enforceable by the federal government.

NMFS regulations require that applicants for incidental harassment authorizations prepare a Plan of Cooperation (POC) that identifies measures that have or will be taken to minimize adverse effects on the availability of marine mammals for subsistence purposes. Although POCs are not structured as “consensus” agreements (as are CAAs), they are enforceable.

Oil Spill Response Capabilities in the U.S. Arctic

In 2014, the National Research Council’s report, Responding to Oil Spills in the U.S. Arctic Marine Environment, highlighted the lack of adequate oil spill response tools, capabilities, and infrastructure for any large spill that might occur in the U.S. Arctic. The report, sponsored in part by the Commission, called for testing of current and emerging technologies in realistic conditions, using carefully controlled field experiments. The report recommended the use of a rigorous decision process, such as the Net Environmental Benefits Analysis, to evaluate different response options and associated environmental impacts that may result. Response options identified for the Arctic include biodegradation, chemical dispersants, oil herding agents, in situ burning, and mechanical containment and recovery (learn more about potential impacts of response activities on marine mammals); however, additional research is needed to inform decision-making regarding response options under various scenarios. The severe shortage of housing, fresh water, food, sewage handling and garbage removal facilities, communications infrastructure, supplies, and hospitals and medical support were cited as a major limitation in launching an effective response effort in the Arctic. The report noted that better communication and planning is needed among the various federal and state agencies that would be involved in oil spill response and with international partners, such as Canada and Russia. Also needed is oil spill training for local communities and integration of local traditional knowledge of ice and ocean conditions and marine life to enhance the effectiveness of oil spill response.

BSEE has increased efforts to conduct oil spill response research after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and has funded efforts to expand research on response equipment and methods in icy conditions, such as the effectiveness of dispersants in ice, in situ burning in ice conditions, and remote sensing of oil in and under ice. BSEE has also finalized drilling regulations for the Arctic to prevent an oil spill, and is developing stronger analytical capabilities to model spill trajectories and worst case discharge scenarios and to conduct training and drills in the event of a spill.

The oil and gas industry also has significant responsibilities to enhance oil spill response capabilities in Arctic conditions. Currently, the majority of resources and trained personnel for oil spill response in the Arctic are located in the Beaufort Sea, near Prudhoe Bay. However, additional capabilities are under development on the Northwest Coast of Alaska, along the Chukchi Sea coast. A number of international oil and gas companies have launched a collaborative effort to enhance Arctic oil and gas capabilities globally as part of the Arctic Oil Spill Response Technology Joint Industry Programme.

In 2013 the Arctic Council’s Working Group on Emergency Prevention Preparedness and Response (EPPR) developed an Agreement on Cooperation on Marine Oil Pollution, Preparedness and Response in the Arctic. The voluntary agreement, signed by the United States and several other Arctic nations, is intended to strengthen cooperation, coordination, and mutual assistance among the signatories on oil pollution preparedness and response in the Arctic. In 2017, EPPR and BSEE convened a workshop to share information and discuss the latest advances in oil spill response technology and best practices relevant to the Arctic region. A follow-up workshop to discuss next steps specific to international collaboration on oil spill response research was held in 2019 in Norway; a link to the report of that workshop is available here.

Marine Exchange Alaska’s AIS Receiver and Transmitter Stations

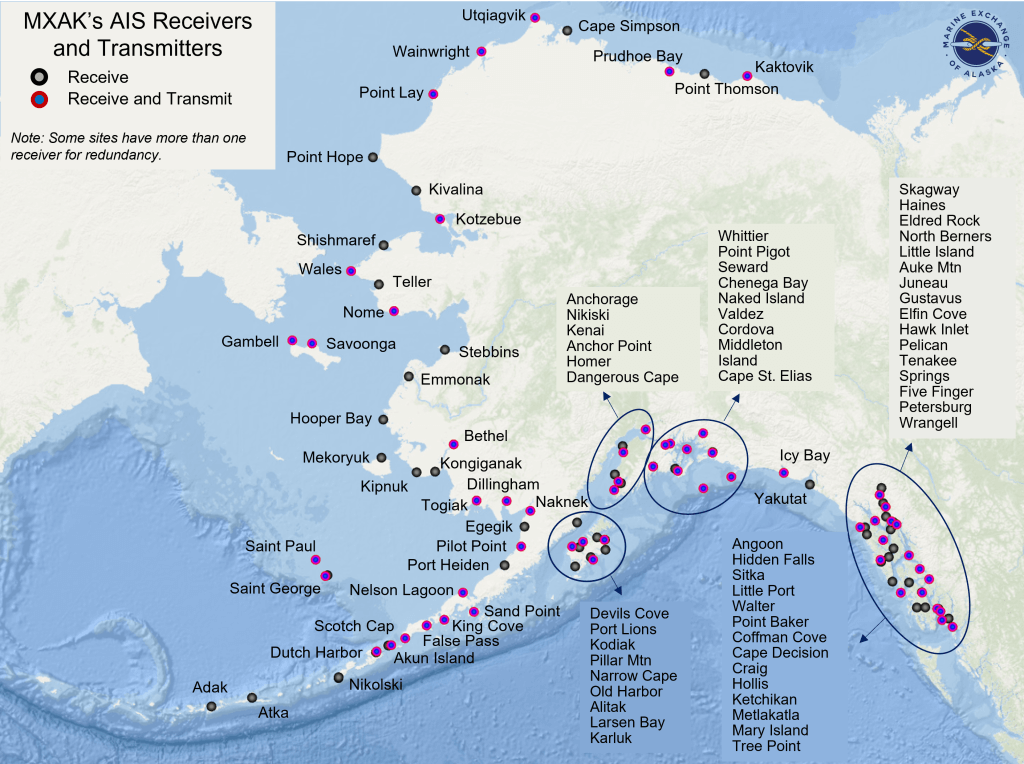

Recognizing that oil spill prevention and avoidance of maritime accidents are much more cost-effective than oil spill response and clean-up, the non-profit Marine Exchange of Alaska (MXAK) has developed an expansive vessel tracking system in Alaska with over 125 Automatic Identification System (AIS) receiving stations to aid safe, secure, efficient and environmentally sound maritime operations. Vessel owners, operators, ports, the Coast Guard, the State of Alaska and other authorized users may view vessels’ locations via MXAK’s secure system. MXAK staff track vessel movements to provide valuable safety, navigational and logistics information to the maritime community and to provide a virtual “Safety Net” that also contributes to the efficiency of maritime operations.

Marine Mammal Response in the Event of an Oil Spill

Responsibility for responding to Arctic marine mammals in the event of a spill requires a coordinated effort among federal, state, and local agencies, Tribes, industry partners, and contracted Oil Spill Removal Organizations. These entities follow response protocols as prescribed in the Wildlife Protection Guidelines for Oil Spill Response in Alaska.

Partly in response to the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill both FWS and NMFS have developed marine mammal-specific oil spill response guidelines, and have conducted training, workshops, and drills for their designated marine mammal stranding response organizations and veterinarians. For example, NMFS’s Pinniped and Cetacean Oil Spill Response Guidelines and Arctic Marine Mammal Disaster Response Guidelines provides information and guidance on communications with other responders and the public, documentation of injuries (including sample data collection forms), care and rehabilitation of oiled animals, and making informed decisions for appropriate response during an oil spill event to supplement existing guidance in the Alaska Area Contingency Plans and the NMFS Pinniped and Cetacean Oil Spill Response Guidelines.