Florida Manatee

The Florida manatee, a subspecies of the West Indian manatee, is a large, slow-moving marine mammal with an elongated, round body and paddle-shaped flippers and tail. Manatees are herbivores, feeding solely on seagrass, algae and other vegetation in freshwater and estuarine systems in the southeastern United States. Florida manatees can be found as far west as Texas and as far north as Massachusetts during summer months, but during the winter, manatees congregate in Florida, as they require warm-water habitats to survive. Abundance of the subspecies has increased over the last 30 years, which prompted the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to downlist the West Indian manatee from endangered to threatened in 2017. However, due to their slow speed and relatively high buoyancy, manatees are often struck by vessels, which is the primary cause of human-related deaths of the species. Additionally, manatees continue to be threatened by loss of warm-water habitat and periodic die-offs from red tides and unusually cold weather events. Florida manatees are managed jointly by both FWS and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC).

Florida manatees at Three Sisters Spring, Crystal River, Florida. (Cynthia Taylor, Sea to Shore Alliance)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

The most recent state-wide abundance estimate is 9,790 manatees. That includes approximately 4,630 manatees on the west coast of Florida and 5,160 manatees on the east coast. Those estimates are based on aerial surveys that were conducted in 2021 and 2022 and represent an increase from the last state-wide abundance estimate of 8,810, despite the unusual mortality event that was declared on the east coast in 2021.

Florida manatees have been divided into four regional management units: the Atlantic Coast, Upper St. Johns River, Northwest, and Southwest. The 2021 estimate on the west coast is similar to the estimate from 2015, however, estimates of individual management units reflect a potential shift in distribution between surveys. On the east coast, the Upper St. Johns River estimates were similar in 2016 and 2022, while the abundance of the Atlantic coast management unit unexpectedly increased during that time.

Distribution

The Florida manatee occurs only in coastal and inland waters of the southeastern United States, where it occupies the northern limit of the species’ range. Because prolonged exposure to water temperatures below 18°C (65°F) can be lethal to manatees, Florida manatees are confined largely to the southern two-thirds of the Florida Peninsula in winter. There they aggregate at warm-water springs and thermal outfalls from power plants, or remain along the edge of the Everglades at the southern tip of the state. As water temperatures rise in spring and summer, Florida manatees disperse throughout the state and into neighboring states.

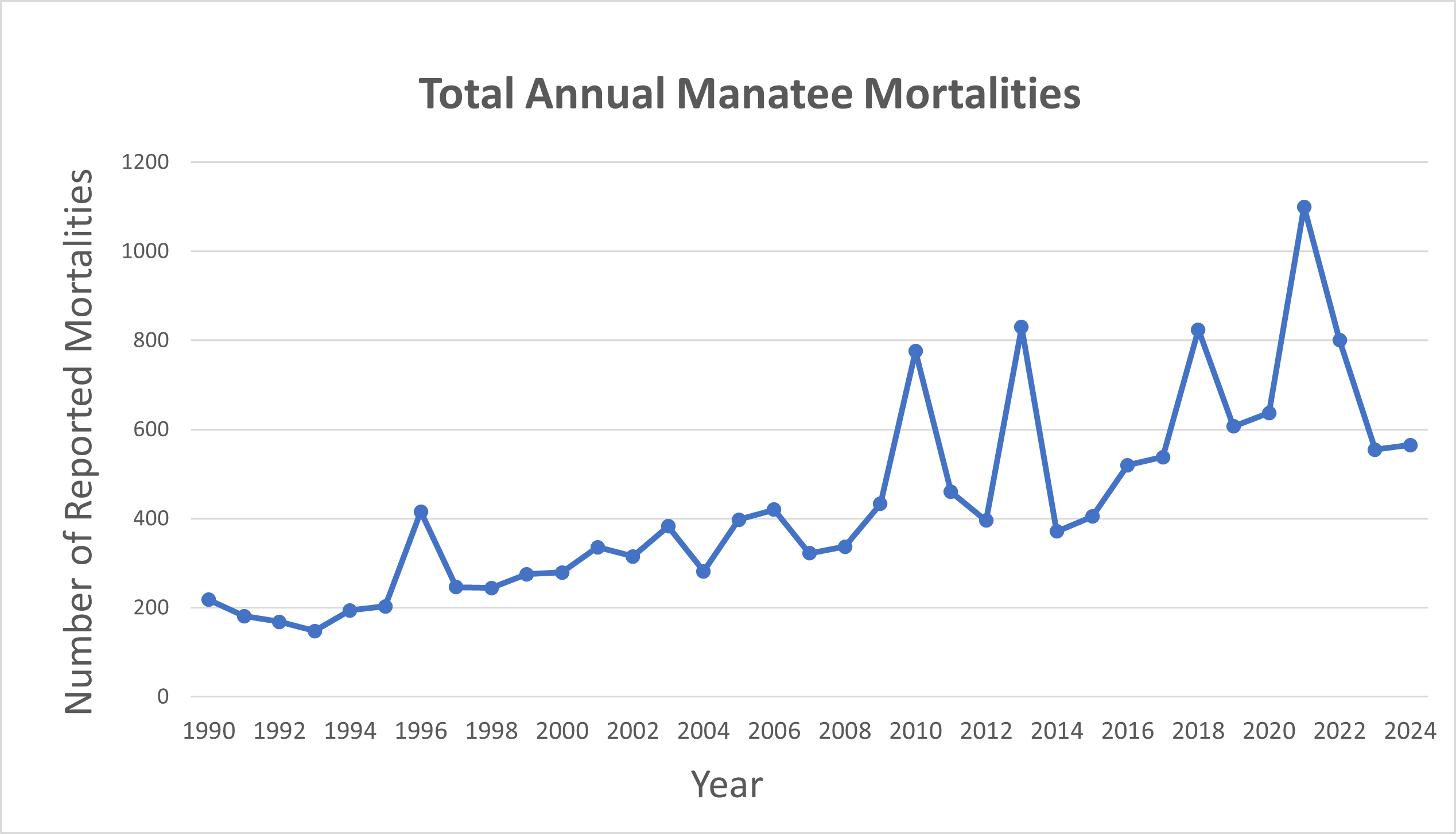

Total number of reported manatee mortalities, 1990 to 2024.

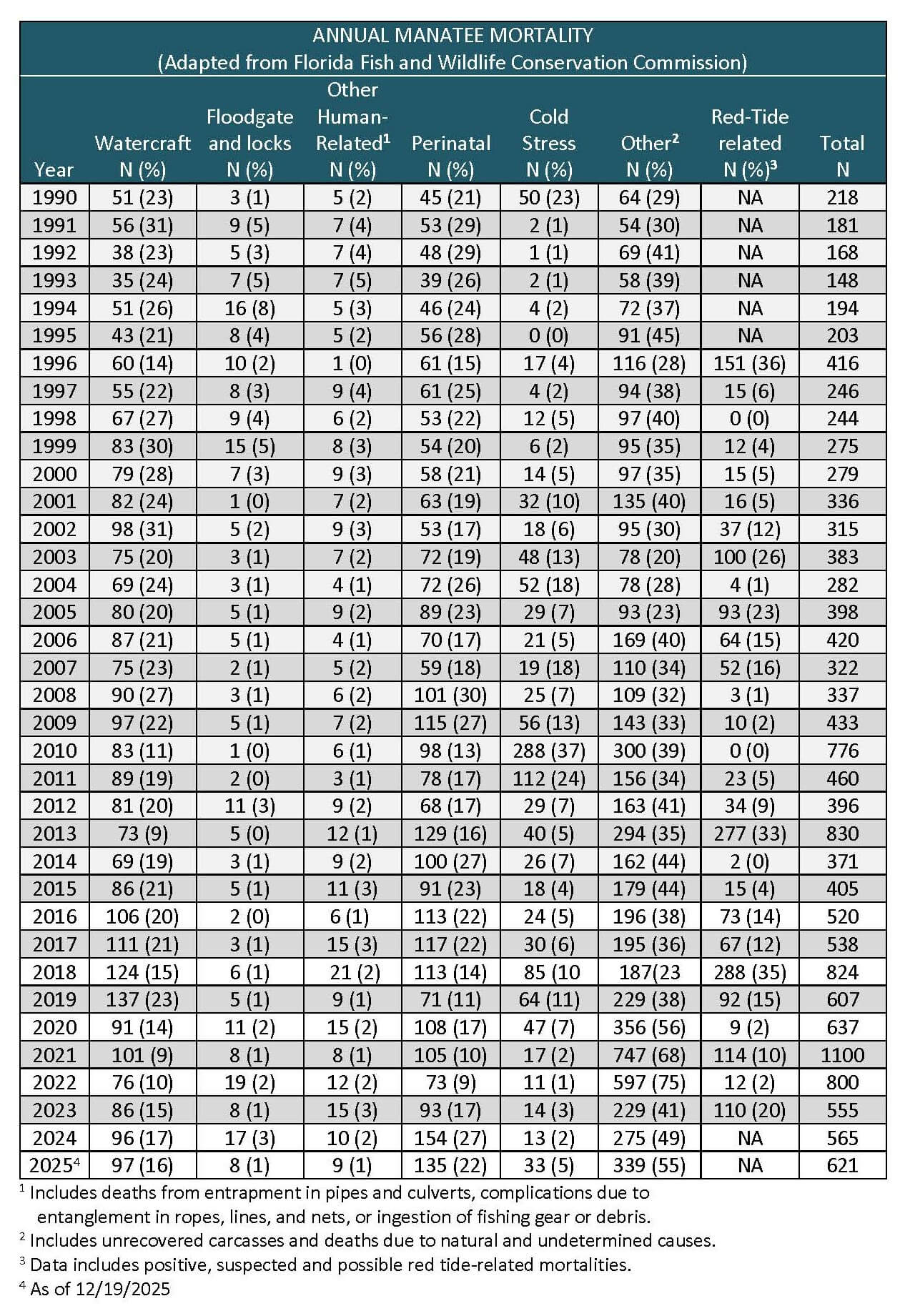

Unusual Mortality Event: 2020 to 2022

Beginning in December 2020, a drastic uptick in carcasses and manatees requiring rescue was observed along the Atlantic coast of Florida. The increased number of stranded and dead manatees led FWS to declare an unusual mortality event (UME) in March 2021 that lasted until April 2022. FWC recorded a total of 1,255 mortalities during the period of the UME. Agencies and partners from the Manatee Rescue and Rehabilitation Partnership also helped to rescue 137 manatees statewide. The UME was officially closed on March 14, 2025.

The high mortality was caused by starvation due to lack of forage in the Indian River Lagoon (IRL) where, for over a decade, phytoplankton blooms fueled by excess nutrient loading have led to extensive seagrass losses. The IRL provides vital habitat for manatees in all seasons and is central in manatee migration on the Atlantic coast. Consequently, malnourished manatees were documented well beyond the IRL all along Florida’s Atlantic coast. Colder temperatures added extra health stressors to manatees already compromised by chronic malnutrition.

In December 2021, several environmental organizations announced their intent to sue the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for failing to reinitiate consultation with FWS under the section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, specifically regarding inadequate water quality standards set by EPA that now adversely affect manatees. The Commission sent a letter to FWS in December 2021 recommending that FWS increase the capacity of rehabilitation and other facilities to house manatees, approve contingency sites for the temporary holding of manatees, incorporate expert findings into any supplemental feeding program, and continue to work closely with FWC and other members of the Manatee Rescue and Rehabilitation Partnership to obtain funding to increase facility capacity and to respond to and rehabilitate live-stranded manatees.

During the winter months, the impacts of seagrass loss are most severe, as manatees rely on warm-water sites to maintain their body temperature. FWS implemented a pilot supplemental feeding program in the winter of 2021-2022 in Indian River Lagoon to help sustain manatees through the cold months until warmer temperatures allowed animals to disperse and find alternative foraging sites. The supplemental feeding trial continued during the winter of 2022-2023, with over 399,000 pounds of romaine lettuce fed to the manatees at a single site. The supplemental feeding program was discontinued in the 2023/2024 winter season because seagrass monitoring efforts indicated adequate foraging resources.

FWS and FWC, in collaboration with the Manatee Rescue and Rehabilitation Partnership, continue to prioritize responding to and rehabilitating live animals in distress. In the long-term, efforts are underway to restore seagrass beds and natural warm-water habitat for manatees.

Endangered Species Act listing

The Florida manatee is a subspecies of the West Indian manatee, which, until 2017, was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). However, in 2012, FWS received a petition requesting that all West Indian manatees, including Florida manatees and the second subspecies, Antillean manatees, be reclassified from endangered to threatened under the ESA. In April 2017, FWS officially downlisted the species. In its final rule, the agency cited that the West Indian manatee had met the downlisting criteria established in the 2001 Florida Manatee Recovery Plan and thus warranted reclassification from endangered to threatened.

Given the extreme number of manatee mortalities along the Atlantic coast during the UME, there was growing support for uplisting the species to endangered once again. FWS initiated a five-year status review of the West Indian manatee in July 2021. The purpose of the review was to assess ongoing conservation efforts and ensure that listed species are appropriately classified under the ESA. In November 2022, FWS received a petition requesting that the West Indian manatee be reclassified as endangered. FWS found that the petition presented substantial information and announced their intent to complete a status review in October 2023. In January 2025, FWS announced the completion of their 5-year review of the West Indian manatee and, based on their findings, they issued a proposed rule to amend the listing of the West Indian manatee by replacing it with two separate listings for each subspecies, the Florida manatee and the Antillean manatee. The rule proposes to retain the threatened status for the Florida manatee and uplist the Antillean manatee to endangered.

In 2024, FWS announced their intention to revise the critical habitat designation for the Florida manatee, which was originally designated in 1976. They also plan to designate critical habitat for the Antillean manatee in Puerto Rico.

More Information

What the Commission Is Doing

Legal Protection

In response to the 2016 proposed listing change of the West Indian Manatee by FWS, the Commission submitted a letter recommending that the two subspecies, the Florida manatee and the Antillean manatee, be considered separately. The Commission noted that despite an increase in the population size of Florida manatees, the growth of the population over the past 30 years has remained slow while manatee mortalities continue to reach record highs. The Commission also expressed concern with the loss of warm-water habitat due to eventual retirements of power plants over the next 30 to 40 years. This could threaten the future manatee population in Florida and reverse past recovery progress.

In addition, the Commission opposed changing the listing status for Antillean manatees, which, outside of Puerto Rico, continue to face considerable threats from habitat loss and degradation, hunting, fisheries bycatch, pollution, and human disturbance. The Sirenia Specialist Group of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimates that only about 2,500 mature Antillean manatees remain and projected that the subspecies would decline by 20 percent over the next two generations (40 years) in the absence of effective responses to current and projected anthropogenic threats.

FWS downlisted the West Indian manatee from endangered to threatened on 5 April 2017. However, the January 2025 proposed rule, if finalized, would amend the listing such that the Florida manatee remains listed as threatened and the Antillean manatee be uplisted to endangered. The Commission submitted a letter in response to this proposal, supporting the proposal to list the two subspecies separately, and recommending that FWS reconsider uplisting the Florida manatee to endangered, given the impacts of the UME and ongoing stressors including cold stress, harmful algal bloom events, loss of seagrass, and impacts from power plant closures.

The Commission remains committed to engaging with federal, state, and local authorities to ensure adequate protections continue for the species and regularly participates in stakeholder meetings hosted by FWC. We continue to support an assessment of the potential harmful impact on manatees of a reduction in warm-water refuges through the retirement of power plants, as well as the effectiveness of boat speed restrictions.

Manatee Harassment

The Commission has also been concerned about the harassment of manatees by swimmers, divers, and kayakers at the Kings Bay warm-water refuge in the town of Crystal River, and particularly at Three Sisters Springs, the site’s largest spring. Parts of Kings Bay, including Three Sisters Spring, are managed as part of the FWS’s Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge. In August 2014, the Save the Manatee Club petitioned the FWS to close Three Sisters to human access during the winter manatee season. In response, the Commission wrote to the FWS in November 2014 noting the urgent need for further steps to reduce harassment in the spring and repeated past recommendations that the FWS adopt a no-touch policy and a minimum approach distance for swimmers.

In early 2015, the Commission conducted a site visit to Crystal River and met with involved federal, state, and local officials as well as local citizens and environmental group representatives to review manatee management efforts and plans at Crystal River. These matters were further considered during the Commission’s 2015 annual meeting. During the winter of 2014-15, Refuge staff temporarily closed Three Sisters Spring to human access on several occasions when high numbers of manatees were present in the spring. In 2017, FWS released an updated management plan for Three Sisters Spring, which includes guidelines to close the spring to public access when water temperatures in the region drop to 17 degrees Celsius.

Commission Reports and Publications

See Florida manatee sections in chapters on Species of Special Concern in past Annual Reports to Congress.

Laist, David W., Taylor, Cynthia, and Reynolds, John E. III. 2013. Winter Habitat Preferences for Florida Manatees and Vulnerability to Cold.

Laist, David W. and Shaw, Cameron. 2006. Preliminary Evidence that Boat Speed Restrictions Reduce Deaths of Florida Manatees.

Laist, David W. and Reynolds, John E. III. 2005. Influence of Power Plants and Other Warm-Water Refuges on Florida Manatees.

Laist, David W. and Reynolds, John E. III. 2005. Florida Manatees, Warm-Water Refuges, and an Uncertain Future.

Lowry, Lloyd, Laist, David W., and Taylor, Elizabeth. 2007. Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters.

Taylor, Cynthia R. 2006. A Survey of Florida Springs to Determine Accessibility to Florida Manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris): Developing a Sustainable Thermal Network.

Weber, Michael L. and Laist, David W. 2007. The Status of Protection Programs for Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| March 14, 2025 | |

| December 13, 2022 | |

| December 2, 2021 | |

| April 8, 2016 | Letter to FWS on proposed reclassification of the West Indian manatee from endangered to threatened |

| November 24, 2015 | |

| September 28, 2015 | |

| September 4, 2015 | |

| December 30, 2014 | Letter to FWS on proposed measures for manatee viewing at the Crystal River National Wildlife Refuge |

| November 3, 2014 | Letter to FWS on a petition to designate Three Sisters Spring as a manatee sanctuary |

| September 2, 2014 | Letter to FWS_on a petition to reclassify West Indian manatees from endangered to threatened |

| September 21, 2011 | |

| August 22, 2011 | Letter to FWS on a proposed rule to establish a manatee refuge in Kings Bay, Florida |

| April 26, 2010 | Letter to FWS on reconvening the manatee recovery team and warm water task force |

| January 14, 2010 | Letter to FWC on a draft final endangered and threatened species listing process rule |

| October 29, 2009 | |

| September 10, 2009 |

Learn More

Threats

Along the east coast of Florida, loss of seagrass, an important food source for manatees, may pose the greatest threat to the species and was considered the driving factor of the Unusual Mortality Event (UME) from 2020 to 2022. A 95% reduction of seagrass since 2011 has largely been attributed to increasing harmful algal blooms and reduced water quality.

Cold stress poses another threat to manatees and was likely a contributing factor to the increase in manatee mortalities in 2021. As manatees continue to lose warm-water habitat from the destruction of natural springs and the closure of power plants, full recovery of the species becomes more difficult.

In addition, collisions with boats are a frequent and increasing cause of human-related deaths, as propellers and boat hulls can inflict serious or mortal wounds. Vessel-related deaths reached a new peak in 2019, with 137 manatees stuck and killed by boats, which tops the previous record of 124 vessel-inflicted mortalities set in 2018.

Manatees can also be killed by neurotoxins associated with red tides that occur most often in southwest Florida. These toxins can be inhaled when they surface to breathe in affected areas, or ingested when they eat sea grass encrusted with tunicates that accumulate the toxins. In 2018, an unprecedented number of manatees died from a large and persistent red tide outbreak in southwest Florida. Harmful algal blooms are also thought to be a contributing factor to the loss of seagrass in estuaries along the Florida coasts.

Instances of manatee harassment are also a problem in areas of naturally occurring warm-water springs. When humans disturb manatees, it can alter their natural behaviors important for survival.

Annual Florida manatee mortality from 1990 to 2025. Annual number and percentage (in parentheses) of known Florida manatee deaths in the southeastern United States (excluding Puerto Rico).

Current Conservation Efforts

On-the-ground manatee conservation efforts coordinated jointly by FWS and FWC are geared toward continuing to recover manatees and mitigating the impacts of ongoing threats. Such activities include assessing the abundance of the Florida manatee population, tracking manatee movements through photo-identification and satellite-linked radio telemetry, developing a Warm-Water Habitat Action Plan to provide guidance for research and management of warm-water habitats into the future, including improving manatee access to natural warm-water systems, rescuing and rehabilitating distressed manatees, responding to and investigating manatee mortalities, responding to reports of manatee carcasses, enforcing site-specific boat speed zones, and strengthening management efforts to prevent harassment by divers at Crystal River.