Hawaiian Monk Seal

The Hawaiian monk seal is the most endangered pinniped in U.S. waters and one of the most endangered seals worldwide. Most Hawaiian monk seals live in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI) where their numbers have declined since the 1950s. Since the 1990s, a small population in the main Hawaiian islands (MHI) has increased significantly in size and now represents a quarter of the species’ total population size.

The name monk seal is believed to come from the resemblance of folds of skin around the neck to the cowl of a monk’s hood. The Hawaiian name for the monk seal is Ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua, meaning dog running in the rough seas. Monk seals feed primarily on a wide array of small fishes, squids, octopuses, and crustaceans, found on the sea floor on sand flats, outer reef slopes, offshore banks and coral reefs. The dives of most seals are to 60 meters or less, although some seals have been recorded diving to depths of more than 500 meters.

Monk seal on rocky beach in the French Frigate Shoals, NWHI. (Brenda Becker, NOAA)

Species Status

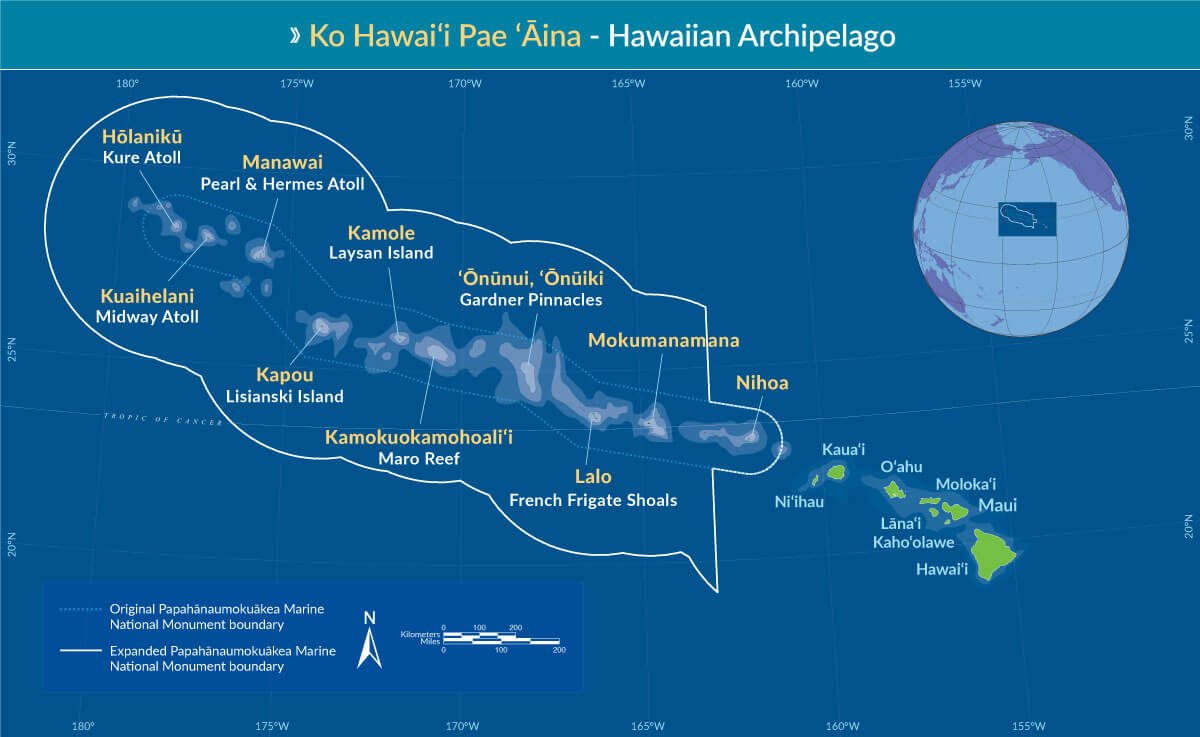

Hawaiian monk seals occur almost exclusively in the Hawaiian Archipelago, with occasional sightings at Johnston Atoll. Most monk seals are found at eight primary sites: Necker Island, Nihoa Island, French Frigate Shoals, Laysan Island, Lisianski Island, Pearl and Hermes Reef, Midway Atoll, and Kure Atoll) in the remote, largely uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI). All of these islands are now part of the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument. Along with the Mediterranean monk seal, the Hawaiian species is one of only two remaining monk seal species. A third species, the Caribbean monk seal, went extinct in the 1950s.

Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument (https://www.papahanaumokuakea.gov)

Hawaiian monk seals were apparently extirpated from the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) after Polynesians arrived. In the late 19th century, hunting in the NWHI pushed the species to the brink of extinction. Their numbers had rebounded substantially by the late 1950s. Subsequently the population declined again over the next 50 years to a level 70% lower than that of the late 1950s. This decline is not fully explained but was likely due to multiple factors, including variable oceanographic productivity and human disturbance. Fortunately, beginning in 2013 the total population of Hawaiian monk seals throughout their range began to increase (Baker et al 2016); a hopeful sign.

Threats to the species differ substantially between the NWHI (where they are now well protected from direct human interactions), and the MHI (where human-related impacts pose a significant and growing challenge) (Baker et al. 2011). In the NWHI, the major threats include entanglement in marine debris (particularly abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG)), starvation due to limited prey availability, shark predation, attacks on pups and females by aggressive adult male seals, and loss of pupping beaches due to rising sea levels. In the MHI, threats include fishery interactions (hookings and drowning in gillnets), toxoplasmosis (an infectious disease spread by cats), and intentional killing by people (Harting et al. 2021).

Learn more about Threats to Hawaiian Monk Seals.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is the lead agency responsible for monk seal research and management but it relies on partnerships with other agencies (e.g., the State of Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, U.S. Coast Guard, and U.S. Navy), non-governmental groups (e.g., The Marine Mammal Center, Hawaii Marine Animal Response), and volunteers. NMFS adopted a recovery plan for Hawaiian monk seals in 1983 that was updated in 2007, and designated revised critical habitat in 2015.

In January 2016, NMFS released a new Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan. The management plan is an important step toward successfully managing the MHI monk seal population, preparing to address emerging challenges, and fostering co-existence between humans and seals.

What the Commission Is Doing

We have participated in and attended meetings of the NMFS Hawaiian monk seal Recovery Team and have convened Hawaiian monk seal program reviews. We have also organized and supported workshops on priority research and management needs, and interventions such as vaccination and seal rehabilitation. We support monk seal research and conservation projects, including a recently published analysis of demographic patterns in monk seal entanglement (Baker et al. 2025) and an ongoing collaboration with NOAA and The Marine Mammal Center to elucidate factors that influence the efficacy of rehabilitation and release of young, undernourished monk seals.

Commission Reports and Publications

See Hawaiian Monk Seal sections in chapters on Species of Special Concern in past Annual Reports to Congress.

Lowry, Lloyd F., Laist, David W., Gilmartin, William G, and Antonelis, George A. 2011. Recovery of the Hawaiian monk seal: a review of conservation efforts, 1972 to 2010, and thoughts for the future

2002. Final Report: Workshop on Management of Hawaiian Monk Seals on Beaches in the Main Hawaiian Islands

Laist, D., Reynolds, J.E. III, Boness, D.J., Gale, N., Gerrodette, T., Lowry, L.F., and Ragen, T.J. 2002. Hawaii monk seal program review. A report to the Marine Mammal Commission, 33 pp

Reports prepared for the Marine Mammal Commission:

Lowry, Lloyd, Laist, David W., and Taylor, Elizabeth. 2007. Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. Waters – A Review of Species Classification Systems and Listed Species

Weber, Michael L. and Laist, David W. 2007. The Status of Protection Programs for Endangered, Threatened, and Depleted Marine Mammals in U.S. waters

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| November 17, 2011 | |

| October 24, 2011 | Letter to NMFS on proposed activities to enhance monk seal recovery |

| August 5, 2011 | Letter to NMFS on proposed rules to expand monk seal critical habitat |

Learn More

Threats

Hawaiian monk seals face a variety of threats, including entanglement, prey limitation, shark predation, fishery interaction, intentional killing, loss of terrestrial habitat to rising sea levels, and disease. For more, visit our Threats to Hawaiian Monk Seals page.

Current Conservation Efforts

Enhancing Hawaiian monk seal recovery

Numerous recovery activities covered by a 2014 final programmatic environmental impact statement (PEIS) have been conducted, including pup translocations to improve survival, vaccination of wild monk seals to prevent or mitigate morbillivirus outbreaks, behavioral modification measures to enhance seal and public safety in the MHI, and the use of uncrewed aerial vehicles and new devices for studying seal movements and behavior. In 2025, NMFS obtained a 5-year permit, which allows continued research and conservation actions. Rehabilitation of seals in poor health is undertaken under the authority of NMFS’ Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program. A previous study found that between 17 and 24 percent of all seals alive in 2012 had either benefited directly from conservation interventions or were descendants of seals that had benefited from such interventions between 1980 and 2012 (Harting et al. 2014).

Monk Seals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Each year, NMFS’ Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center sends field teams to most of the major subpopulations in the NWHI to monitor seal abundance, survival, and pup production, and to mitigate factors likely to cause monk seal deaths. Teams disentangle seals, and a large-scale effort to remove marine debris from the seals’ habitat has reduced entanglement risk according to a recent paper published in Science. Other conservation measures include efforts to mitigate shark predation, reunite or foster unpaired pups with mothers, intervene to deter attacks by aggressive male seals on other seals, and move pups from sites with low survival to sites with higher survival. Regarding the latter, a study found that the survival of 19 weaned pups was greatly improved by moving them between subpopulations during 2012-2014 (Baker et al. 2020). NMFS also works with The Marine Mammal Center to treat seals for injuries, rehabilitate undernourished pups and juveniles and release them back to the wild.

Monk Seals in the Main Hawaiian Islands

Hawaiian monk seal numbers in the MHI have increased substantially from at least the early 1990s and continue to grow. While this has been a bright spot for the species status, it has raised many new and difficult research and management challenges, including the mitigation of interactions between seals and nearshore fisheries, beachgoers, swimmers, and divers, and disease transmission to Hawaiian monk seals from domestic and feral animals. For example, toxoplasmosis, a protozoal disease spread to monk seals and other native Hawaiian wildlife through the feces of cats has resulted in the documented deaths of monk seals (Barbieri et al 2016). There are hundreds of thousands of outdoor cats in the MHI.

Monk Seal Health Care Facilities

In 2014, The Marine Mammal Center of Sausalito, California, a non-profit veterinary research and rehabilitation center for injured and sick marine mammals, opened a new health care center for monk seals. Located on land owned by Natural Energy Laboratory Hawaii Authority in Kailua-Kona on the Island of Hawaii, the $3.2 million facility was funded entirely with private donations raised by the Center. Named Ke Kai Ola, meaning “healing sea,” the monk seal hospital holding pools are able to provide long-term care for up to ten seals. The hospital also includes pens to hold seals in isolation when needed, a medical building with a laboratory and food preparation area, and an open-air education pavilion for visitors.

Since early July 2014, Ke Kai Ola operations have included nursing undernourished seals (primarily yearlings and pups) from the NWHI back to health before their transport and release back in the NWHI. The majority of seals rehabilitated thus far have been females, which could markedly increase the reproductive potential of the wild population.

Also in February 2014, a monk seal holding and care facility dedicated to monk seals became operational at NOAA’s Inouye Research Center at Pearl Harbor on Oahu. This facility includes four above ground pools, a complete necropsy laboratory, and a state-of-the-art veterinary laboratory for surgical and other veterinary procedures. The facility has been used to perform several monk seal dehookings and emergency surgeries, and to provide outpatient care for seals prior to their release back into the wild.

Additional Resources

NMFS – Hawaiian Monk Seal Updates

A Substantial Reduction in Seal Entanglement

From Past Patients to New Moms

Frequent Questions: Hawaiian Monk Seal Mothers and Pups

NMFS – 2023 Hawaiian Monk Seal Stock Assessment Report

Hawaiian Monk Seal Population Surpasses 1,500!

NMFS – 2016 Main Hawaiian Islands Monk Seal Management Plan

NMFS – Hawaiian Monk Seal – Conservation and Management

NMFS – Hawaiian Monk Seal – Science