Threats to Hawaiian Monk Seals

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Food Limitation

Variable juvenile survival strongly influences monk seal population trends. This has been noted since the late 1980s, when survival of young seals began to decrease in the largest monk seal subpopulation at French Frigate Shoals. Although a variety of factors affect juvenile survival, underweight and starving pups and juveniles with no evidence of underlying disease indicate that low prey availability is a significant threat to their survival. Efforts to mitigate impacts of food limitation on survival through rehabilitation began in the 1980s and continued until 1995, when the program was halted after 11 pup contracted an eye disease of unknown etiology and became blind. The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) made just a few efforts to rehabilitate seals during the almost 20 years that followed. In 2014, a new monk seal hospital, built by The Marine Mammal Center opened, allowing rehabilitation efforts to resume. The facility has successfully treated and released more than 40 underweight young seals, demonstrating that, with appropriate care, rehabilitation offers a potentially significant contribution to recovery for this species.

Translocations (movement of seals from one part of their range to another) have also been used by NMFS for various reasons, including food limitation, and have proven to be a successful tool in Hawaiian monk seal conservation (Baker et al. 2011, Baker et al. 2021).

Shark Predation

In the mid-1990s, shark predation on monk seal pups increased sharply at French Frigate Shoals. Nearly a third of all pups born at the atoll in 1996 were either known or suspected to have been killed by sharks (Harting 2010).

Such predation is believed to have killed 24 percent of the pups born at this atoll between 1997 and 2010. By comparison, pup deaths attributed to sharks at Laysan and Lisianski Islands over the same period amounted to just 2 percent and 4 percent, respectively. Shark predation has remained substantially higher at French Frigate Shoals than at other NWHI sites. In 2013 a third of all pups there were known or suspected to have died of shark attacks. All observed shark attacks at French Frigate Shoals since 1997 have been by Galapagos sharks. It is believed that a small number of sharks have learned to patrol pupping beaches to catch unwary pups. To reduce such deaths, NMFS field teams have moved newly weaned pups to other islets within the atoll where shark predation is less common. This intra-atoll translocation practice is ongoing and to date more than 350 pups have been translocated within the French Frigate Shoals.

To further mitigate shark predation, NMFS has pursued efforts to remove individual Galapagos sharks that prey upon seal pups. NMFS has tested various shark deterrents (Gobush and Farry 2010), but those methods proved ineffective. Studies of shark movements at French Frigate shoals indicate that only about 20-30 of the estimated 600 Galapagos sharks at the atoll patrolled waters near monk seal pupping beaches. Catching the sharks that prey on monk seal pups has continued to prove very challenging, and predation continues to account for a large portion of pup mortality at French Frigate Shoals.

Entanglement in Marine Debris

Since 1982, NMFS field teams have documented more than 400 seals entangled in marine debris, including derelict fishing gear. Huge amounts of marine debris are transported to Hawaii from throughout the North Pacific by ocean currents. The total number of seals that drown at sea or die of entanglement-caused wounds when biologists are not present is unknown. Most entangled seals are weaned pups. Nearly all known entanglements have occurred in the NWHI, with relatively few in the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI).

In addition to disentangling animals, field crews have been removing hazardous debris from NWHI beaches since the early 1980s. In 1996, work also began to remove net debris from shallow waters around NWHI atolls. Debris removal is now coordinated by multiple agencies and non-governmental groups. Since 1996 more than 1100 metric tons of netting and other debris have been removed.

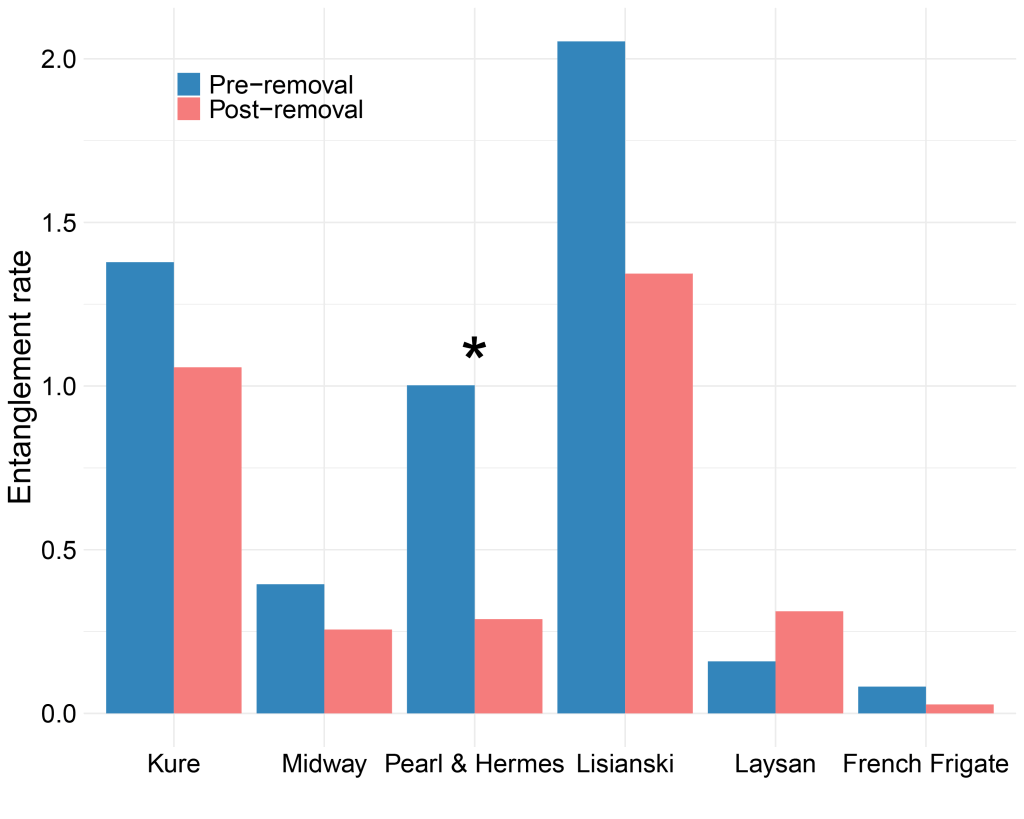

Weaned Hawaiian monk seal entanglement rate (per 1000 observed weaned pup exposure days) before and after initiation of large-scale marine debris removal. Subpopulations are ordered left to right in accordance with their relative location from northwest to southeast. A statistically significant decline in entanglement rates occurred after marine debris removal began at Pearl and Hermes Reef (indicated with an asterisk).

This has likely prevented the death and injury of monk seals, as well as sea turtles, seabirds, fish, crabs, and corals. Since 2020, a non-profit organization, The Papahānaumokuākea Marine Debris Project (PMDP), has been actively removing debris from the Monument. A 2024 study published in the journal Science demonstrated that this large-scale and sustained removal effort has reduced monk seal entanglement risk (figure to the right).

Loss of Terrestrial Habitat

Monk seals require terrestrial habitat to give birth to and nurse their pups. These habitats also provide a space to rest, safe from aquatic predators such as sharks. Loss of suitable habitat for these critical life functions could have a devastating impact on the population. Rising sea levels and increasing erosive impacts of storms are significant threats to these habitats. This has been particularly evident at French Frigate Shoals, where several islets have already been greatly diminished or completely washed away. Efforts to preserve, and ideally restore, terrestrial habitat will likely be essential to ensure the French Frigate Shoals monk seal population remains viable and contributes to the species ultimate recovery (Baker et al 2020).

Main Hawaiian Islands

Deliberate Killing

Since 2009, at least 14 monk seals have been deliberately killed on the MHI. Some additional suspicious cases could not be conclusively attributed to intentional killing. In 2021, at least three monk seals were shot or bludgeoned to death on Molokaʻi. Unfortunately, people killing seals on purpose is one of the top three threats affecting MHI monk seal recovery.

Hookings

In the MHI, monk seals are injured and sometimes die from hooking when taking bait or fish from the lines of nearshore fishermen. NMFS has intervened in dozens of hooking cases with surgeries sometimes required to successfully remove the hook(s). Several animals have had to be handled more than once to remove hooks. This indicates a need for community engagement and increased communication with fisherman to minimize seal-fisher interactions and find alternative solutions, while continuing the de-hooking activities, to reduce this threat.

Disease

Monk seals are vulnerable to infectious diseases spread by pets, feral cats and dogs, rodents, livestock, insects and other vectors introduced into the MHI but not found in the NWHI. Among those of particular concern for monk seals are distemper viruses, Toxoplasma gondii, West Nile Virus, and Leptospira spp. Toxoplasmosis is proving to be a particularly significant threat to monk seals—a disease caused by a parasite shed in cat feces. Since 2004 toxoplasmosis has caused the deaths of more than a dozen monk seals in the MHI. Monk seals are being vaccinated against canine distemper virus with the aim of achieving herd immunity in order to prevent a potential outbreak.

Non-lethal Human Interactions

Beachgoers as well as their pet dogs can disturb seals that haul out on beaches to rest, molt, and rear pups. Such disturbance can force seals into the water interfering with these necessary seal behaviors. In some cases, people have fed seals or otherwise encouraged direct interactions with seals, resulting in their acclimation to people. This, in turn, can increase the possibility of seals approaching and harming people. In the interest of public safety, the seals involved in these interactions are sometimes caught and translocated to areas where they will not interact with people.

At times these interactions have been malicious. In 2016, a man was arrested for approaching a pregnant female monk seal resting on a Kauai beach and striking it in head several times with his fist. Video of the attack was recorded by a passerby on a cell phone and the man was charged with violating MMPA provisions prohibiting harassment of marine mammals. NMFS staff and its partners frequently respond in cases that require seals to be displaced to protect human safety (e.g., seals in semi-enclosed areas with high levels of human activity, particularly involving children) or seal safety (e.g. seals on boat ramps or in polluted canals).

Interventions

As noted above, monk seal research and management staff and their partners undertake a number of interventions each year to address various life threatening or hazardous situations (e.g., dehookings, disentanglement, entrapped animals, clipping umbilical cords, reuniting mothers and pups, treating abscesses, deworming, and hazing animals away from hazardous situations). Between 1980 and 2016, 1,165 interventions were made, including 38 in 2016. Analyses of those cases indicate that about 75 percent of those cases (885 interventions) have probably or likely improved the involved animals’ survival chances. From subsequent information on the survival and reproduction of treated animals, NMFS estimates that up to 28% of the current population has benefited from interventions.