Northern Sea Otter

Sea otters live in shallow coastal waters off the northern Pacific. In the U.S., there are two distinct sea otter subspecies, the Northern sea otter and the Southern (or California) sea otter. Northern sea otters live in the waters off south Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington State.

Sea otters. Photo taken under U.S. FWS permit #MA-043219. (Ryan Wolt)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

Historically, an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 sea otters occurred in coastal waters of the North Pacific Ocean. These populations were decimated by almost two centuries of commercial hunting. Since the 1980s, most northern sea otter populations have continued to recover.

In Alaska there are three stocks of northern sea otters—the Southwest stock, the Southcentral stock, and the Southeast stock. The Southwest stock, which includes otters in the Aleutian Archipelago, the Alaska Peninsula, and Kodiak Island, is listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). The Southcentral and Southeast Alaska stocks continue to grow or have stabilized and are not listed under the ESA. All three stocks in Alaska are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA).

The overall sea otter population size of the Southwest Alaska stock has declined by more than 50% since the mid-1980s. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed the Southwest Alaska stock as threatened in 2005 and designated critical habitat for the population in 2009. That designation includes waters out to either 100 meters from shore or out to the 20 fathom isobaths in most areas within the population’s range. FWS finalized a recovery plan for the Southwest Alaska sea otter in 2013. The most recent population estimate for this stock is 51,935 otters and is reported in the 2023 stock assessment report. It is believed that the overall population trend has stabilized in recent years. The abundance of Southwest Alaska sea otters in the western and central Aleutian Islands, however, declined by nearly 90 percent between the early 1990s and 2005. A less precipitous decline occurred over that same period in the eastern Aleutian Islands. One theory for the observed population declines in these areas is an increase in predation by killer whales. Other theories suggest that the observed declines are attributable to oceanographic changes or fisheries effects. Currently, the population trend in the South Alaska Peninsula is still in decline, while the other populations in Southwest Alaska are stable or increasing.

In contrast to the Southwest Alaska stock, the numbers of otters in the Southcentral and Southeast Alaska stocks have increased or stabilized despite thousands of sea otters from the Southcentral Alaska stock having died in Prince William Sound as a result of the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill. Rebuilding the population took about 25 years. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) published a 2014 report concluding that the population had recovered to pre-spill levels. Population levels in the Southcentral stock have now stabilized and may be increasing; there are estimated to be around 21,600 animals.

The stock of sea otters in southeastern Alaska has grown exponentially since their reintroduction in the late 1960s and have nearly doubled since the early 2000s. This growth, coupled with concern that sea otters are competing with commercial fisheries for sea urchins, sea cucumbers, crabs, and clams has led to calls from Alaska State officials and some fisheries groups for a cull of the population. Although there are now more than 22,000 sea otters in southeast Alaska, the population continues to increase and remains below the region’s estimated carrying capacity of 48,083 sea otters.

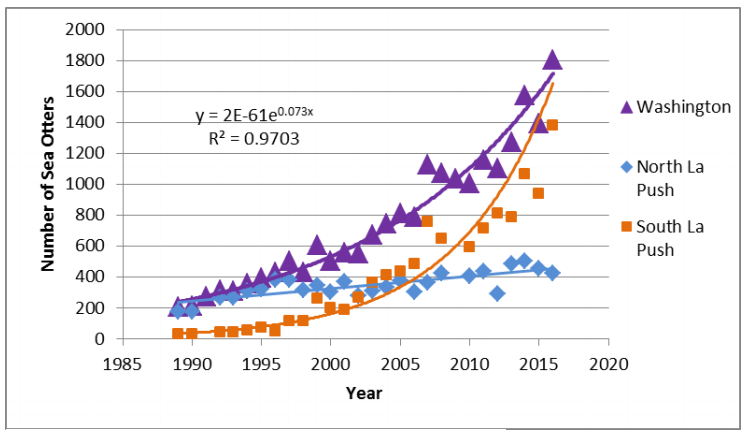

In Washington, sea otters were extirpated by the early 1900s. Around 1970, 59 otters were captured from Amchitka Island in Alaska and released along the outer coast of the Olympic Peninsula. Many of these translocated otters did not survive, but eventually, the population began increasing. The otter population north of La Push appears to be reaching equilibrium density, however the portion of the stock south of La Push has been increasing at approximately 22% per year since 1989. Survey counts in 2016 reported 1,380 otters south of La Push and 426 otters to the north.

Figure Credit: USFWS, “Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris kenyoni): Washington Stock” Stock Assessment Report, 2018 / Jeffries et al. 2016. Washington sea otter growth patterns from 1989 to 2016.

Distribution

Before commercial hunting began in the mid-1700s, an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 sea otters occurred in coastal waters throughout the rim of the North Pacific Ocean from northern Japan to Baja California, Mexico. In 1911, hunting was prohibited under the terms of an international treaty for the protection of North Pacific fur seals and sea otters signed by the United States, Japan, Great Britain (for Canada), and Russia. By then, only a few thousand otters remained. The survivors were scattered among small colonies in remote areas of Russia, Alaska, British Columbia, and central California.

Since the prohibition on commercial hunting in 1911, northern sea otters have recolonized or have been reintroduced into much of their historic range. By the time the MMPA was enacted in 1972, remnant groups in Alaska had grown considerably and, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, several hundred otters were moved from Amchitka Island and Prince William Sound to try to reestablish populations in southeast Alaska and the outer coasts of Washington and Oregon. Historically, the Washington sea otter stock ranged along the Olympic Peninsula coast south to the Columbia River. Currently, these otters are found along the Olympic Peninsula from Pillar Point in the Strait of Juan de Fuca south to Point Grenville on the outer coast.

Oil Spill Impacts

Based on the limited range of the southern sea otter, the threat posed by oil spill prompted this stock to be listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act in 1977. While northern sea otters did not receive a similar listing, oil spills are also a significant threat to these animals; the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 demonstrated the severe and long-lasting impacts of oil spills on this species. Southcentral Alaskan sea otters near Prince William Sound were severely impacted by the Exxon Valdez oil spill. It was estimated that 1,000 to 5,500 sea otters died in the first few months after the spill. In some of the most heavily impacted areas, sea otter mortality approached 90%. While sea otters in this area have rebounded since the spill, long-term spill effects were observed for decades. Based on sea otter diving behavior, a study by the USGS suggested that sea otters in the most heavily impacted areas were still being exposed to oil on a regular basis, resulting in delayed recovery and continued early mortality through 2009. This population of otters was finally determined to be recovered to pre-spill abundance in 2013 (24 years post-spill) and it was concluded that any continued exposure to lingering oil was no longer of biological significance.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Commission is closely following work being done by the FWS, USGS, and others to monitor the status of the Alaska population stocks. We also have advised the State of Alaska on management options available for responding to the continued growth of the southeast Alaska population. The Commission reviewed updated draft stock assessment reports for the three Alaskan northern sea otter stocks in 2023.

Commission Reports and Publications

For more information on Southern sea otters, see the Commission’s 2012 annual report.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| May 8, 2023 | |

| July 24, 2019 | |

| April 18, 2019 | Letter to FWS regarding an incidental take authorization for oil and gas activities in Cook Inlet |

| April 17, 2018 | |

| June 13, 2016 | Letter to FWS regarding an incidental take authorization for oil and gas activities in Cook Inlet |

| September 29, 2014 | Letter to FWS regarding an incidental take authorization for oil and gas activities in Cook Inlet |

| July 17, 2013 | |

| May 17, 2013 |

Learn More

Threats

Northern sea otters face a variety of threats throughout their range. In the western Aleutian Islands, killer whale predation, restricted habitat use, and possibly a decline in the number of otters this habitat can support due to ecosystem-level changes are primary concerns. Elsewhere in Alaska, competition with commercial shellfish fisheries, entanglement in commercial fishing gear, oil spills, disease outbreaks, contaminants, and subsistence harvests are the primary threats.

Current Conservation Efforts

Ongoing conservation efforts are directed at monitoring changes in abundance and distribution of northern sea otters and trying to ascertain the causes of declines in southwestern Alaska. Future actions to conserve the threatened southwest Alaska sea otter population will depend on the results of planned abundance surveys and additional research into the cause or causes of observed declines.

Researchers completed an analysis of carrying capacity for the growing Southeast Alaska stock in 2019 and estimated the carrying capacity for the entire southeast Alaska region to be 74,650 sea otters. The results of this study are expected to inform a determination of the stock’s status relative to its optimum sustainable population level, which in turn will dictate what management options might be available under the MMPA.

In addition, during fiscal year 2021, Congress directed FWS to study the feasibility and cost of re-establishing sea otters where they were once hunted to near-extinction along the Pacific coast in Oregon and Washington. The report is available on the FWS website. FWS determined that reintroduction is feasible, but additional information and stakeholder input are necessary. The Elakha Alliance, a nonprofit group with a mission to restore a healthy population of sea otters to the Oregon coast, is looking to the Congressional request to aid their efforts. The Elakha Alliance believes that the re-introduction of sea otters would make Oregon’s marine and coastal ecosystem more robust and resilient; sea otters’ well-known role in promoting the growth of kelp forests also contributes to carbon sequestration, or the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere, which could play a role in reducing global climate change.

Additional Resources

U.S. FWS Northern Sea Otter species page

U.S. FWS Stock Assessment Reports – Sea Otters

USGS Nearshore Marine Ecosystem Research Program

Alaska Department of Fish and Game Northern Sea Otter species page

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Sea Otter page

Marine Mammal Commission Sea Otter Reintroduction Fact Sheet