Southern Resident Killer Whale

Killer whales are found in every ocean, but they are segmented into many small populations that differ genetically, as well as in appearance, behavior, social structure, feeding strategies and vocalizations. The so-called “Resident” killer whales are fish eaters found along the coasts on both sides of the North Pacific. In the eastern North Pacific, there are three populations of Resident killer whales: Alaska Residents, Northern Residents, and Southern Residents. The Southern Residents, which comprise the smallest of the ‘resident’ populations, are found mostly off British Columbia, Washington and Oregon, but also travel to forage widely along the outer coast. Southern Residents are Chinook salmon specialists. They feed on Chinook year-round, and it is their primary prey in spring and summer when they occupy inland waters. During the fall and winter, when Southern Residents disperse widely, they add other salmon species (Coho salmon in fall and chum salmon in winter) and some demersal fishes to their diet (e.g., halibut and lingcod). Resident killer whales associate in stable matriarchal social units called ‘pods’. There are three pods for Southern Resident killer whales, called the J, K, and L pods. This population was listed as Endangered in Canada in 2001 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, and as Endangered in the United States in 2005 under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Killer whales. (Holly Fearnbach, NOAA)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

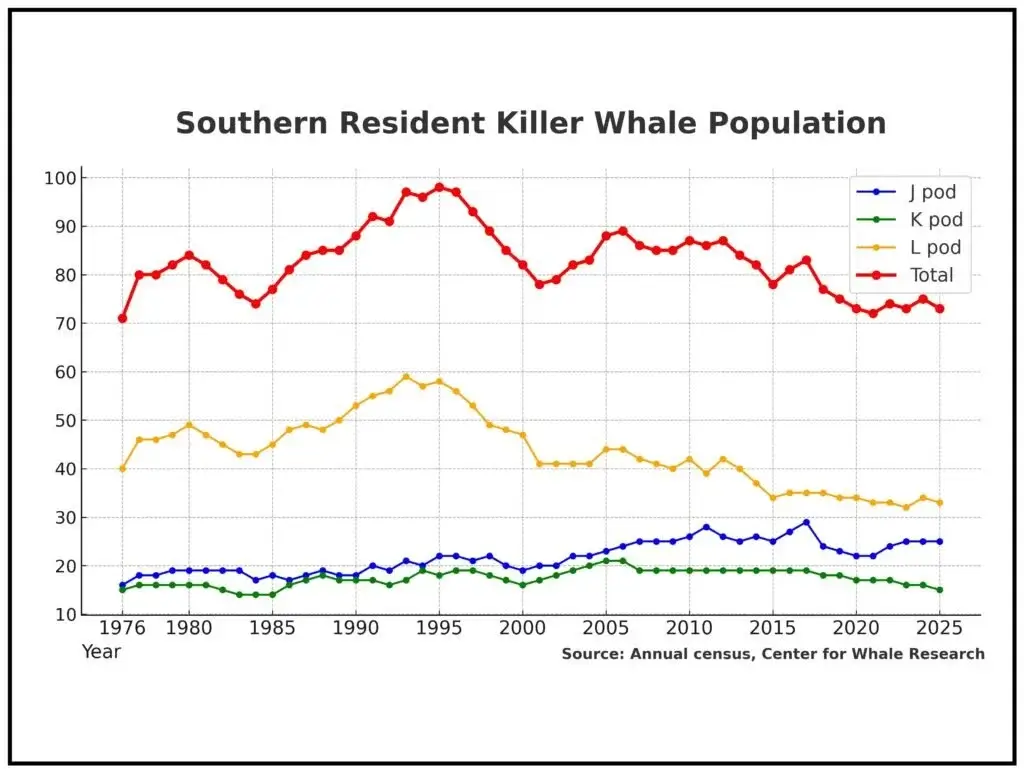

The Southern Resident killer whale population may have numbered more than 200 animals prior to the 20th century. However, with modern impacts on their prey base, opportunistic shootings prior to the 1960s, and the live capture or killing of nearly 70 Resident and Transient killer whales for marine parks and display from 1967 to 1971, the first complete count found just 71 whales in 1974. The population increased to its peak of 96-98 whales in the mid-1990’s following the cessation of killings and captures for marine parks, which stopped after the Marine Mammal Protection Act was enacted in 1972. However, in just five years from 1996 to 2001 the population rapidly declined by 20 percent to 78 whales. Southern Resident killer whale numbers rebounded to 89 by 2006 and stabilized at 85-89 animals through 2011. However, after 2011 the population again entered a period of decline, and as of July 2025 stands at just 74 whales.

Most Southern Residents live within their natal pod and interact with members of other pods several times a year. The three Southern Resident pods (J, K and L) differ in several characteristics, including pod size, dialect and home ranges. Within each pod, there are several family units that each descend from a single female ancestor. These units, called matrilines, are typically composed of an adult female, the “matriarch”, and her female and male offspring. In several cases, although the matriarch has died, the family unit has remained together.

The sizes, trends in numbers, and demographic patterns have differed among the three pods. The dynamics of the largest pod, L Pod, have largely driven the population trends described above. The pod increased to a maximum of 56-59 whales in the mid-1990s, declined to 34 in 2014, and is currently at 33 individuals. In contrast, the next largest pod, J Pod, increased slowly in size from 16 whales in 1976 to 28 in 2010, fluctuated between 25 and 30 whales through 2016, but then suffered nine deaths through 2019; there are now just 27 whales in the pod. It is this pod that has been responsible for the recent decline in the total population size. The smallest pod, K Pod, has shown only a very slight numerical increase from 14-16 whales from the late 70s through the early 80s, to 18-21 whales through 2006. However, the pod size is currently at 14 whales.

A census of the Southern Resident killer whale population by the Center for Whale Research (CWR) shows the population trends through time (CWR, July 2025).

Distribution

The three Southern Resident killer whale pods have distinct seasonal distributions along the West Coast, primarily influenced by the movements of Chinook and other salmon runs. During late spring, summer, and fall, all three pods typically frequent the Salish Sea, which includes the Strait of Georgia, Strait of Juan de Fuca, and Puget Sound, though their use of this core summer habitat has declined significantly from 2004 to 2020. From late fall through spring, all three pods generally shift to outer coastal waters, ranging from Southeast Alaska to central California. J pod tends to remain closer to inland waters, while K and L pods more commonly range offshore, particularly from the western entrance of the Strait of Juan de Fuca to Point Reyes, California.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Marine Mammal Commission has long been concerned about the fate of Southern Resident killer whales, hosting the first workshop focusing on killer whales in Seattle in April 1975. The Commission continues to evaluate and provide scientific and policy recommendations to federal agencies to support the recovery of Southern Resident killer whales. Our efforts focus on improving population monitoring, protecting critical habitats, reducing vessel disturbances, and ensuring the availability of key prey species, such as Chinook salmon. In May 2018, the Commission held its annual meeting in Seattle, and Southern Resident killer whales were a primary focus of the meeting. Issues such as the population’s status and trends, the factors affecting its health and viability, research being conducted on it, and conservation/management efforts being taken on its behalf, were on the agenda.

In 2022, the Commission was a member of the Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary’s Advisory Council Whale Reporting Working Group. The Working Group was established to provide recommendations on the protection of threatened and endangered whale species that depend on Olympic Coast National Marine Sanctuary’s habitats for critical life processes, including the Southern Resident killer whale. The Working Group provided final whale conservation recommendations in early 2023.

Commission Reports and Publications

See the Southern Resident killer whale sections in chapters on Species of Special Concern in past Marine Mammal Commission Annual Reports to Congress.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| March 11, 2024 | |

| September 25, 2023 | |

| August 2, 2021 | |

| December 4, 2020 | |

| December 31, 2019 | |

| December 18, 2019 | |

| October 29, 2018 | |

| October 5, 2018 | |

| August 30, 2018 | |

| March 31, 2017 | |

| August 13, 2013 | |

| February 4, 2013 | Letter to NMFS addressing a petition to delist Southern Resident killer whales |

| January 15, 2010 | |

| March 2, 2007 | |

| August 14, 2006 | |

| March 22, 2005 |

Learn More

Threats

The ongoing decline of the Southern Resident killer whale population is most likely due to three distinct threats: decreased quantity and quality of prey, the presence of persistent organic pollutants, and disturbance from vessel presence and noise.

Prey Limitation

Reduced prey availability, particularly of declines of Chinook salmon populations, is a major threat to the Southern Resident killer whale population. Declines in the abundance of many stocks of Chinook salmon may be correlated to decreased reproductive rates and increased mortality rates of Southern Resident killer whales. Current research also suggests that with fewer salmon available, Southern resident killer whales may be shifting their foraging behavior due to prey scarcity, including spending less time in traditional foraging areas and moving greater distances to find suitable prey.

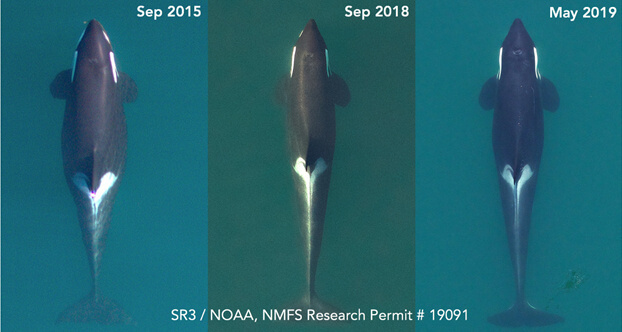

Aerial photographs of J17, documenting a progression of the malnourished individual (SR3/NMFS NOAA Permit #19091). In extreme cases, the fat deposits on each side of the whale’s head are so low that it is described as ‘Peanut Head’, shown here.

Contaminants

Southern Resident killer whales spend much of their lives in inland waters that are near sources of pollutants that enter the marine ecosystem through industrial runoff, agricultural practices, and wastewater. These contaminants bioaccumulate in the food web, particularly in fish species like Chinook salmon, which the whales rely on for food. As a result, the whales can accumulate high levels of persistent organic pollutants (POPs), such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), pesticides, and heavy metals, in their bodies over time. If a whale encounters a period of low prey abundance, it will mobilize energy in its fat reserves, thus releasing those pollutants into its bloodstream, which can degrade the whale’s health, affect its reproductive potential and even lead to death.

Vessels

Vessels are prevalent in the Salish Sea, traveling to and from Vancouver, Seattle, Tacoma, and many smaller ports. Vessels both large (such as cargo ships, container ships, and ferries) and small (such as commercial whale-watching boats, recreational fishing vessels, and other recreational/private vessels) can cause disturbance based on their physical presence in proximity to the whales. In addition, sound emitted from certain vessels may exacerbate that disturbance by interfering with whale echolocation used to find food and communicate with one another. Southern Resident killer whales exhibit a variety of responses to the presence of vessels, including altering their behavior and modulating their vocalizations, which can negatively impact the ability of whales to forage successfully and acquire the energy and nutrients needed to survive and reproduce.

Current Conservation Efforts

Southern Resident killer whales were listed as endangered under the ESA in 2005, and a recovery plan was completed in 2008. After a 2021 five-year ESA review, NMFS concluded that “the overall status of the population is not consistent with a healthy, recovered population”, and that “Southern Resident killer whales remain in danger of extinction.” The review identified new research and conservation efforts to build upon past activities and NMFS has since focused resources on saving the Southern Residents through the “Species in the Spotlight” program.

Following ESA-listing of the population, NMFS designated critical habitat in the inland waters of Washington in 2006. In response to a petition received in 2014 and a lawsuit in 2018, NMFS proposed a critical habitat designation for coastal waters from Washington to Central California used by Southern Resident killer whales, and important habitat features such as prey availability and water quality. While the Commission supported the areas included in the proposed critical habitat, it recommended in a 19 December 2019 letter that NMFS should include sound as a separate essential feature of the critical habitat.

In addition to federal conservation action by the NMFS and Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans, the state of Washington has dedicated considerable effort to reducing the threats faced by the whales. In 2018, Washington Governor Jay Inslee issued an executive order that established the Southern Resident killer whale Task Force to assist the state in identifying, prioritizing and supporting the implementation of an action plan for the recovery of Southern Resident killer whales. The Task Force, comprised of members from state, Tribal, and local governments, the State Legislature, businesses, and nonprofits, developed recommendations designed to increase the availability of Chinook salmon to Southern Resident killer whales, and decrease the risk to the whales from vessels, noise and contaminants. Washington state currently tracks progress updates on the implementation of these recommendations.