Southern Resident Killer Whale Population Details

Historical Demographics

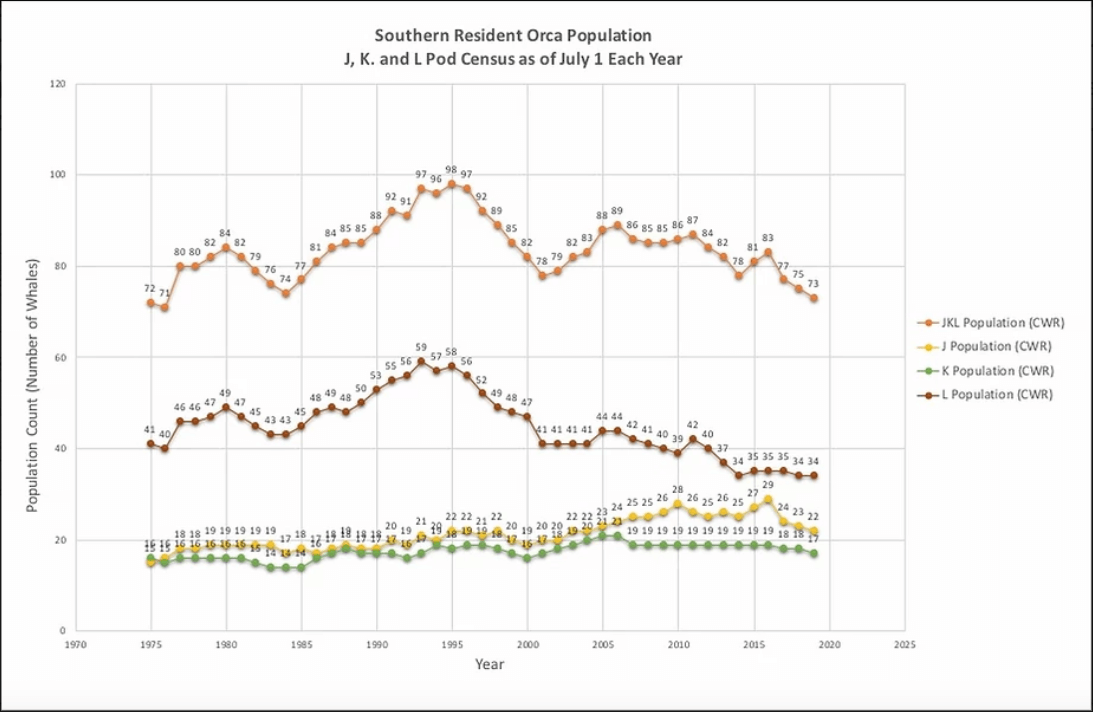

The Southern Resident killer whale population may have numbered more than 200 animals prior to the 20th century. However, with modern impacts on their prey base, opportunistic shooting prior to the 1960s, and the live capture or killing of nearly 70 Resident and Transient killer whales for marine parks and display from 1967 to 1971, the first complete count found just 71 whales in 1974. With the cessation of capture and shootings, the population slowly increased to a peak of 96-98 whales in the mid-1990s. However, in just five years from 1996 to 2001 the population rapidly declined by 20 percent to 78 whales. This population was listed as Endangered in Canada in 2001 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, and as Endangered in the United States in 2005 under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Southern Resident killer whale numbers rebounded to 89 by 2006 and stabilized at 85-89 animals through 2011. However, after 2011 the population again entered a period of decline, and as of October 2020 stands at just 74 whales. The population was that small last in 1984.

A census of the Southern Resident killer whale population by the Center for Whale Research (CWR) shows the population trends through time (CWR, July 2019).

From 1984 to 2011, there were two to six births in the population in most years (average=3.85 per year). However, from 2012 to 2014 there were just four births in total (average=1.33 per year). Somewhat encouragingly, in 2015 seven calves were documented, which was the second largest, single-year number of births. Unfortunately, no calves were born in 2017, and the one calf born in 2018, by late September, died shortly after its birth. Two calves were born in 2019 and are still alive as of October 2020. Two additional calves have been born in 2020. From 2012 to through 2020 there were 17 births (average=1.9 per year), 11 of which have survived. Scientists are concerned that the ratio of male to female births has been skewed in recent years. In the last 22 years (1999-2020), there have been 34 known calves born that survived long enough for their gender to be determined. Only ten (29%) of those calves were females. Because a population’s reproductive output is dependent more on the number of females than males, this male-biased sex ratio among the juvenile whales limits the population’s reproductive potential and chance of recovery. Population viability analyses suggest that if reproductive rates remain low then the population is going to continue to decline.

Individuals and Pods

Most Southern Residents live their lives within their natal pod and interact with members of other pods several times a year. The three Southern Resident pods (J, K and L) differ in several characteristics, including pod size, dialect and home ranges. Within each pod there are several family units, each descended from a single female ancestor. These units, called matrilines, are each typically composed of an adult female, the “matriarch”, and her female and male offspring. In several cases, although the matriarch has died, the family unit has remained together. A few matrilines are functionally extinct as they are composed only of one or more males.

Among those lost in late 2016 was the whale known as ‘J2’, the matriarch and second known member of the ‘J’ pod. Estimated at over 80 years, she was the oldest known Southern Resident killer whale. As part of photogrammetric studies of Southern and Northern Resident killer whales, John Durban and Holly Fearnbach of the National Marine Fisheries Service reported that she looked thin in the early fall of 2016 just prior to the last time she was seen alive. The effect of the loss of a matriarch is not known, but research has suggested that post-menopausal, female killer whales make important contributions to their pods. They appear to lead the pod, presumably using their accumulated knowledge of the environment to find prey. They also appear to support individuals in other ways, as sons who lose their mothers are three times more likely to die.

In recent years, aerial images taken from micro-copters (small rotary-winged drones) have been used increasingly to assess the body condition and health of cetaceans, including the Southern Resident killer whales. Recently published research found declining body condition in 11 of 59 Southern Resident killer whales photographed in 2008 and 2013, two of whom died shortly after being found in poor condition. In 2018, a young female, J50, was found to be in very poor condition. NMFS and other organizations put together a plan to give her antibiotics and to try to supplement her diet. Antibiotics were administered and she was presented with live Chinook salmon, although it could not be ascertained whether she ate any of them. Unfortunately, her condition did not improve, and she has not seen since.

The sizes, trends in numbers, and demographic patterns have differed among the three pods. The dynamics of the largest pod, L Pod, have largely driven the population trends described above. The pod increased to a maximum of 56-59 whales in the mid-1990s, declined to 34 in 2014, and is currently at 33 individuals. In contrast, the next largest pod, J Pod, increased slowly in size from 16 whales in 1976 to 28 in 2010, fluctuated between 25 and 30 whales through 2016, but then suffered nine deaths through 2019; there are now just 24 whales in the pod (due to recent births). It is this pod that has been responsible for the recent decline in the total population size. The smallest pod, K Pod, has shown only a very slight numerical increase from 14-16 whales from the late 70s through the early 80s, to 18-21 whales through 2006, a growth rate of approximately two percent per year. However, the pod size is currently at 17 whales, as of October, 2020. No calves have appeared in K Pod since 2011. A healthy population would grow substantially faster. For example, the Alaska Resident killer whale population has been increasing in recent years at a rate of 3.5 percent. While there have been 19 known births in J and L pods in the last 10 years, only one calf, born in 2011, has been seen in K Pod during that period.