Southern Sea Otter

Sea otters live in shallow coastal waters in the northern Pacific Ocean. Two sea otter subspecies occur in the United States, the southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) and the northern sea otter (E.l. kenyoni). Southern sea otters, also known as California sea otters, live in the waters along the central California coastline. Historically, sea otters numbered in the hundreds of thousands in the North Pacific Ocean, but due to the fur trade, their numbers plummeted in the early 1900s. The threat to the southern sea otter posed by oil spills prompted its listing as a threatened species in 1977.

Sea otter. (U.S. FWS)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

Before commercial hunting began in the mid-1700s, an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 sea otters occurred in coastal waters throughout the North Pacific Ocean. In 1911, hunting was prohibited under the terms of an international treaty for the protection of North Pacific fur seals and sea otters signed by the United States, Japan, Great Britain (for Canada), and Russia. By then, only a few thousand otters remained, including a small colony of about 50 otters along the coast of central California. By the time the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) was enacted in 1972, the California population had grown from as few as 50 to more than 1,000 individuals (an average annual growth rate of about 5 percent).

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed the southern sea otter population as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1977 and adopted a recovery plan for the population in 1982, which was updated in 2003. The recovery plan specifies that the species should be considered for delisting when the average population level over a three-year period exceeds 3,090 animals.

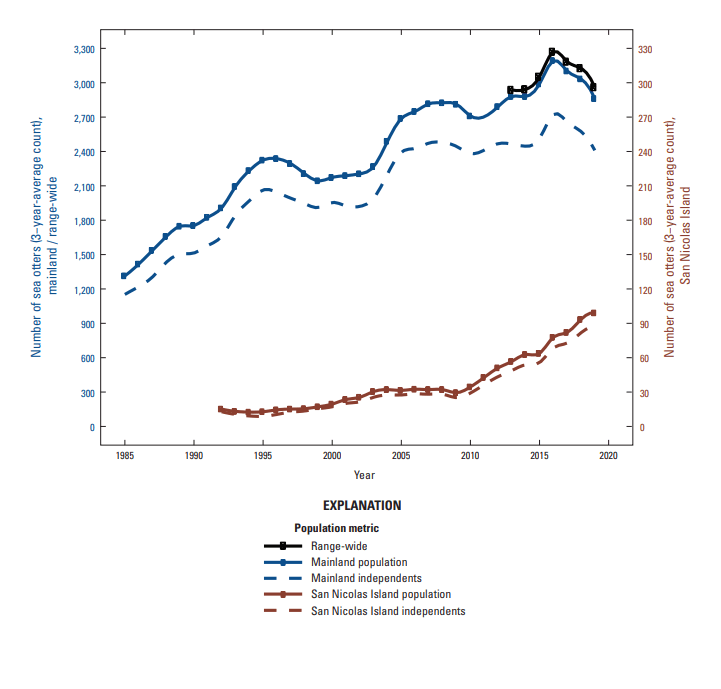

The FWS estimated that southern sea otter abundance in 2016 was 3,272 individuals, a record high since 1972. The 2017 count declined somewhat, to 3,186 otters, but still exceeded the potential delisting threshold for a second straight year. The population has continued to decline, with a most recent abundance estimate of 2,962 otters in 2019. Full surveys were not completed from 2020 through 2023, however, a range-wide southern sea otter census survey was conducted in 2024. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) is currently developing a new statistical model to better account for variations in survey areas and detection efforts to more accurately estimate the population size of southern sea otters.

According to the 2021 stock assessment report, the observed decline through 2019 reflects lower numbers of otters in the northern and southern portion of the mainland range, offset somewhat by continued growth of the central portion of the mainland range and the translocated population at San Nicolas Island. The declining mainland counts since 2017 could be due to increased mortality from shark bites and other causes such as harmful algal blooms and disease.

California Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) Census Results, Spring 2019. Trends in southern sea otter abundance based on 3-year running averages of raw survey counts. Solid lines represent all sea otters and dashed lines represent independents only (non-pups). (USGS)

Distribution

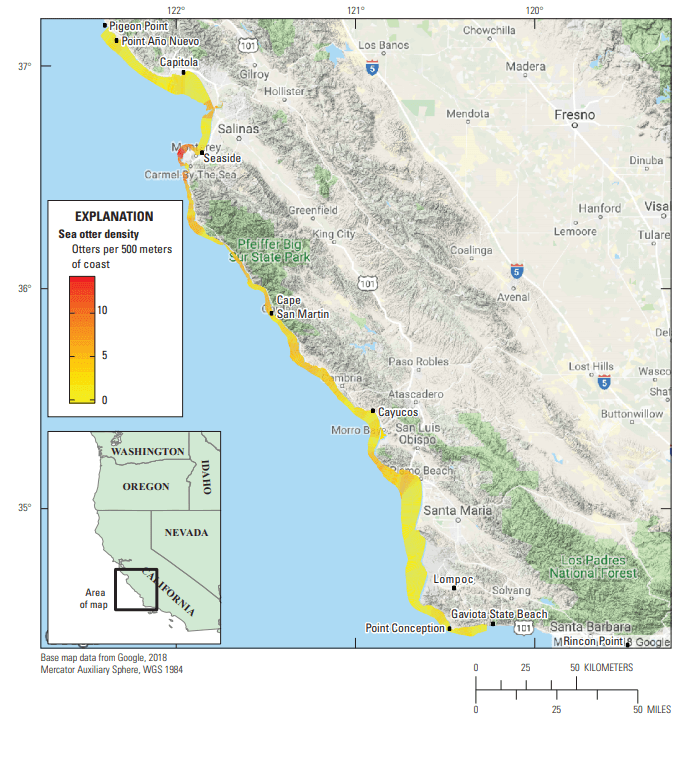

Historically, sea otters occurred in coastal waters throughout the rim of the North Pacific Ocean from northern Japan to Baja California, Mexico, with southern sea otters ranging from Oregon to Baja California. Following almost two centuries of commercial hunting, sea otter populations were severely reduced; surviving southern sea otters consisted of a small colony of otters along the remote Big Sur coast of central California. Between 1911, when hunting was prohibited, and 1972, when the MMPA was passed, these otters recolonized more than 200 miles (370 kilometers) of the California coast. Today, southern sea otters occupy approximately 13% of their historic range; their current distribution extends along the central California coast from Monterey Bay to Point Conception. Mortality from shark attacks has been more frequent at the northern and southern extremes of population’s range and may be a factor in preventing or slowing range expansion of the population into seemingly suitable habitats.

California Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris nereis) Census Results, Spring 2019. Southern sea otter population density along the California coast. San Nicolas Island is not shown because spatially explicit analyses were not conducted there. (USGS)

San Nicolas Island Translocation Attempt

One of the primary threats to the southern sea otter is the risk of an oil spill. To reduce the risk of a large oil spill contacting otters throughout all or much of the species’ range, the FWS, in the late 1980s, attempted to establish a separate population at San Nicolas Island through a translocation of otters from the mainland range. The population never grew as expected and in 2012, the FWS declared the translocation a failure. The FWS determined that moving the otters that remained on San Nicolas Island would likely result in several deaths to the animals and decided to allow the otters to remain at the island. Despite the translocation having been declared a failure, the population on San Nicolas Island continues to increase. The population has grown by about 10 percent per year over the past decade and contained about 146 otters in 2023.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Commission continues to follow ongoing research into the status and trends of this population, both for the coastal “parent” population and the translocated population on San Nicolas Island. The Commission also consults periodically with the FWS and marine mammal facilities to resolve questions about the placement of non-releasable otters from this population.

In 2017, the Commission commented on proposed revisions to the southern sea otter stock assessment report. The draft report identified the potential for sea otters to become trapped in gear used to catch crab, lobster, and finfish. The Commission identified a need to establish an observer program with sufficient coverage to obtain reliable information on the rate and circumstances surrounding the entrapment of sea otters in such gear. The Commission also recommended that, as a precautionary measure, gear modifications to reduce entrapment of sea otters be adopted for crab and lobster traps, similar to those that have been in place for finfish traps since 2002. In addition, the Commission noted the need to update the southern sea otter stock assessment report more frequently. The FWS published a notice of availability of the revised stock assessment report on 28 August 2017, in which it addressed the comments submitted by the Commission and others.

In 2020, the Commission commented on more proposed revisions to the stock assessment report. The Commission recommended ways to improve the potential biological removal estimate. Given that southern sea otters have failed to significantly expand their range over the past two decades and the recent decline in the population trajectory, the Commission also recommended that the FWS make its stock assessment reviews available annually. The revised stock assessment report was made available on 24 June 2021.

Commission Reports and Publications

For more information on southern sea otters, see the Commission’s 2012 annual report.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| April 27, 2020 | Letter to FWS regarding the draft revised stock assessment report for the southern sea otter |

| March 13, 2017 | Letter to FWS with comments on the 2016 draft stock assessment report for the southern sea otter |

| January 25, 2017 | |

| August 3, 2012 | Letter to FWS regarding revised stock assessment report for the Southern sea otter |

Learn More

Threats

While sea otters are vulnerable to natural predators such as sharks, the population also faces risks from other factors such as disease, contaminants, harmful algal blooms, availability of prey, and entanglement in commercial fishing gear. In addition, the risk of oil spills remains an ongoing concern.

In response to a 2021 petition to delist the southern sea otter, FWS conducted a species status review and determined that southern sea otters would retain their status as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act due to threats from shark bite mortality, range curtailment, and impacts of climate change.

Current Conservation Efforts

Sea otter conservation and recovery can provide broader ecological benefits, including improved health and resilience of kelp forests, invasive species control, reduced coastal erosion, and increased carbon sequestration. Current conservation efforts center on monitoring the status, trends, distribution, and causes of mortality of otters in this population. A key indicator of recovery of the population is its ability to expand its range along the California Coast. Currently, it appears that shark predation is an important factor limiting range expansion, particularly in the northern end of the range.

Future actions to promote the conservation and recovery of the southern sea otter will depend on the results of ongoing research, particularly if needed to respond to human-caused sources of mortality. FWS, U.S. Geological Survey, and their partners are expected to continue to conduct annual abundance surveys and respond to strandings, including conducting necropsies to identify the causes of death for retrieved carcasses.