Western North Pacific Gray Whales

A western North Pacific population of gray whales historically migrated along the coasts of Russia, Korea, Japan, and China and was thought to be extinct after being decimated by commercial whaling before the 1970s. Small numbers of gray whales were discovered in the 1990s off Sakhalin Island, Russia, and recent conservation efforts focused on mitigating the impacts of rapidly expanding offshore oil and gas development in that region and on reducing the risk of entanglement in fishing gear. Satellite telemetry, photo-identification, and genetic studies provided new insights on the movements and phenology of gray whales throughout the North Pacific and raised new questions concerning the relationships of the Sakhalin whales to other gray whales in the North Pacific.

Gray whales are known for their long annual migration between high-latitude summer feeding areas and lower-latitude wintering areas. (Shutterstock)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

The western North Pacific population of gray whales is listed as an endangered distinct population segment under U.S. law and it is an endangered subpopulation according to the the Red List of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The population (stock) structure of gray whales has long been under investigation (Supplement 22: 166-174). There are multiple feeding aggregations and multiple stocks but there is also much uncertainty about stock delineation. In the western North Pacific, a Western Feeding Group feeds off Sakhalin Island and southern Kamchatka. This group may include whales that breed in Asia and others that breed largely with one another while migrating to Mexico in the late autumn. In 2020, based on photo-identification and genetic data, an estimated 220-270 whales (excluding calves) were regularly feeding in the summer and early autumn off Sakhalin, the number having more than doubled since the early 2000s.

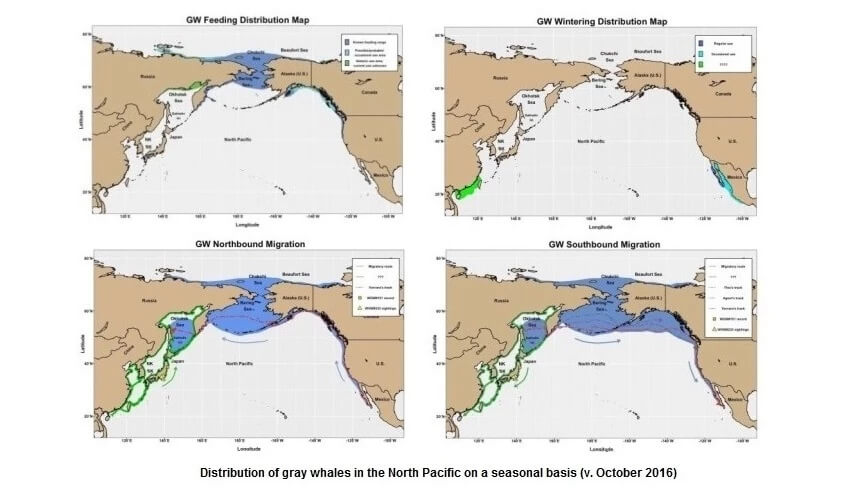

Distribution

Photographic and genetic matches, as well as satellite tracking results, have shown that some of the Sakhalin-Kamchatka whales, after foraging in summer and fall in the western North Pacific, migrate across the southern Bering Sea and Gulf of Alaska to Canada and the U.S. Pacific Northwest, then southward to Mexico for the winter. At least some of those whales then return to Russia in the spring.

The migratory routes and winter habitats of other Sakhalin-Kamchatka whales are uncertain. Western North Pacific gray whales historically ranged southward from the Sea of Okhotsk, along the coasts of Korea and Japan to traditional wintering areas in southern China. While there is evidence that some of those that feed off Sakhalin move south to at least Japan in the winter, it is uncertain to what extent the traditional wintering areas in Asia are still used by gray whales. A photo-identified individual moved back and forth between Sakhalin and the Pacific coast of Honshu, Japan between 2014 and 2016, and a 13-m female died in fishing gear off Baiqingxiang, China, in the Taiwan Strait in November 2011. Recent acoustic evidence from the U.S. Navy was interpreted as suggesting that some gray whales move through the East China Sea, travelling south in the fall and north in the spring.

Western North Pacific gray whale distribution on a seasonal basis (International Whaling Commission, 2016).

Science Provides Clues About Whale Migration

Satellite telemetry, photo-identification, and genetic studies have documented the movements of individual gray whales between feeding areas in the western North Pacific and wintering areas in Baja California, Mexico.

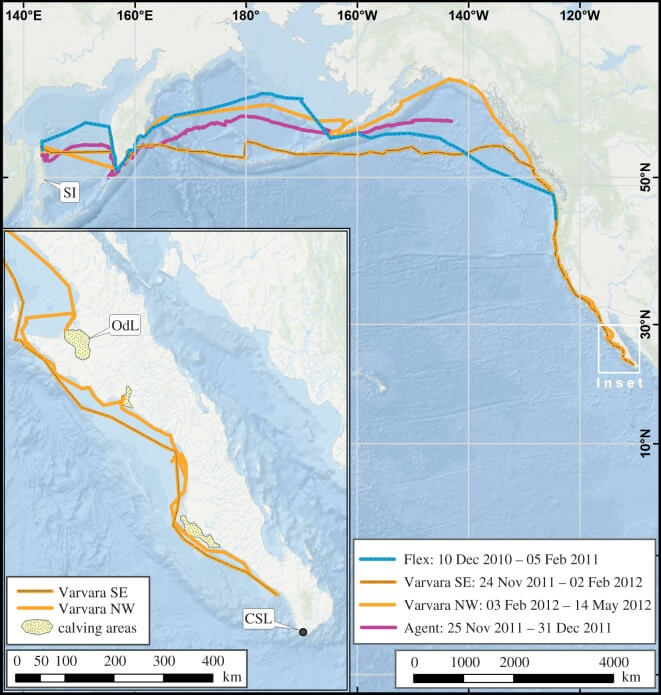

A Russia-U.S. research team satellite-tagged gray whales at Sakhalin Island in 2010 and 2011. In the first successful deployment on October 4, 2010 the investigators tagged a 13-year old male gray whale in the feeding area off Piltun Lagoon along the northeastern Sakhalin coast. The whale, nicknamed “Flex,” remained within 45 km of the tagging site for 68 days and left Sakhalin on December 11. Over the next 55 days, Flex migrated across the Okhotsk Sea, the Bering Sea, and the Gulf of Alaska. The tag stopped sending signals on February 5, 2011 when Flex was 20 km off the central Oregon coast (Mate et al., 2015). Six additional tags were deployed in summer 2011 and at the end of December two tags, both attached to young females, were still functioning. These two whales moved on separate tracks away from Sakhalin, east across the Okhotsk Sea to the Kamchatka Peninsula, around its southern tip, and then eastward across the Bering Sea toward Alaska. At the end of December 2011, they were still on separate tracks, but both were southeast of the Aleutian Islands in the Gulf of Alaska. While one signal was soon lost, the transmitter on one of these whales, an 8.5-year-old female nicknamed “Varvara,” continued to transmit until the autumn of 2012. After January 1, 2012, the whale continued to travel south from British Columbia, Canada, along the west coast of the United States and Mexico to almost the southern tip of Baja California. At that point, the whale reversed course and returned north past the major nursery lagoons, along the west coast of North America to Alaska, through the Aleutians and back across the Bering Sea. These migratory movements and this whale’s presence in or near the wintering lagoons coincided with the migratory timing of eastern North Pacific gray whales. By mid-May, Varvara had returned to the original tagging area off Sakhalin where her movements were recorded until the tag ceased to function on or about October 14, 2012. The 22,511 km round trip took 172 days and at the time was believed to be the longest recorded migration of any mammal.

These fascinating tracking results spurred analyses of photo-identification and genetic data which were reported at a meeting of the International Whaling Commission Scientific Committee in 2018. As of 2019, 54 different individual gray whales were known to have visited both Russia and Mexico, confirming that at least 14% of the Sakhalin-Kamchatka whales make the trans-Pacific migration (if not annually then at least in some years) and about 0.5% of the whales that have been photo-identified in the Mexican wintering areas are known to be individuals that also visit Russia in summer and fall. In 2021 model results indicated that at least half of the Sakhalin-Kamchatka whales overwinter in the eastern North Pacific. The size of any current western North Pacific wintering population remains highly uncertain.

Genetic matches between two individual gray whales biopsy-sampled off Santa Barbara, California and known from both biopsies and photo-identification data obtained at Sakhalin provided further evidence of the connection between the western and eastern Pacific.

Routes of three western gray whales migrating from Sakhalin Island (SI), Russia, to the eastern North Pacific. Cabo St. Lucas (CSL) and Laguna Ojo de Liebre (OdL) are labeled on the map inset of Baja California, Mexico. Image credit: Mate et al., 2015.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Commission has been closely involved in consultations and agency discussions concerning the proposal by the Makah tribe in Washington State for an MMPA waiver allowing resumption of the tribe’s subsistence hunt of gray whales. In particular, it contributed to the determination of conditions attached to the permit to ensure, to the greatest extent possible, that individuals from the western North Pacific that migrate seasonally to coastal North American waters would be fully protected. The Commission was a participating party in the public hearing on this matter, held before an administrative law judge in Seattle in November 2019.

Commission Reports and Publications

For more information on Western North Pacific gray whales, see the Commission’s 2010–2011 annual report and 2012 annual report.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| November 13, 2021 | |

| April 19, 2018 | |

| March 13, 2018 | |

| July 11, 2017 | |

| July 31, 2015 | |

| April 24, 2013 |

Learn More

Threats

The threats to gray whales in the western North Pacific include entanglement and entrapment in fishing gear, ship strikes, noise, and habitat degradation. The whales that migrate to North America for the winter face these same threats in the U.S., Canada, and Mexico. The intensity of oil and gas exploration, development, production, and transport at Sakhalin Island is of particular concern as a potential threat to the gray whales that depend on that region for foraging in the summer and fall. Two major offshore oil and gas projects are located near the Sakhalin Island feeding area, and additional projects were underway and planned off Sakhalin and in areas near the whales’ migratory routes when the flow of information from the region was disrupted. The biggest risks from such projects come from underwater noise, including seismic surveys, increased vessel traffic, habitat modification, and the possibility of a major oil spill.

As evidenced by documented deaths in fishing nets in Japan and China as well as observations of entangled animals at Sakhalin, gray whales in Russia, Japan, and China (and Korea if any of the animals still venture into those waters) face the risk of gear entanglement as well as that of vessel strike. An analysis of human-caused scarring on gray whales near Sakhalin Island found that at least 18% of individuals identified between 1994 and 2005 had been entangled at least once.

An unusual mortality event from 2019-2023 affected gray whales along the west coast of North America. Elevated numbers of gray whales in poor body condition have been stranding, and it is unknown if western and eastern North Pacific gray whales are equally affected. During the event, 690 gray whale strandings had been documented. The exact cause(s) of the event is (or are) still undetermined.

Current Conservation Efforts

The discovery of gray whales at Sakhalin Island in the 1990s coincided with growing interest in the area for offshore oil and gas development. This raised concern about the potential impacts of such development on the whales. In 2006, IUCN’s Western Gray Whale Advisory Panel (WGWAP) was established to provide independent advice and recommendations on how the operator of one of the largest oil and gas projects at Sakhalin could minimize risks to the whales and their habitat from the project’s activities, particularly seismic surveys, construction, vessel operations, and oil spills. The WGWAP was disbanded in March 2022, shortly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Also, for nearly 30 years the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) Scientific Committee has provided an international forum for improving knowledge about western gray whales and the measures needed to conserve them. The Scientific Committee completed a range-wide review of population structure and status of gray whales throughout the North Pacific in 2018.

In 2023, NOAA Fisheries completed a 5-year review for the western North Pacific gray whale and concluded that no change to the listing status of the western North Pacific distinct population segment of gray whale was warranted at this time.

Efforts in Alaska and along the U.S. West Coast to reduce entanglement, vessel strike, and disturbance from vessels may also benefit western North Pacific gray whales that migrate to Mexico. Some of those efforts include the creation of marine mammal viewing guidelines in Alaska, the development of innovative fishing gear technologies, the modification of shipping lanes, and the implementation of vessel speed reduction programs.

Additional Resources

The very large body of work produced by IUCN independent scientific review panels on western gray whales is no longer available from IUCN, but a significant portion of the material is posted and publicly available on the IUCN-SSC Cetacean Specialist Group’s website.