The Value of Marine Mammals

A humpback whale feeds near one of the many whale watching boats that visit Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary each year. Photo taken under NOAA Fisheries Permit #775-1875 (Ari Friedlaender, Duke University).

Why should we conserve and protect marine mammals? What is the value of a blue whale to the average American? What is the intrinsic worth of a sea lion? How does a walrus contribute to Alaska Native food security and cultural self-identity?

Conserving marine wildlife can benefit communities all across America in a variety of ways. Studies have shown that certain species of marine wildlife, including whales and dolphins, are increasingly important drivers of economic growth for tourism and related industries. Marine mammals also provide value through “ecosystem services” – benefits that people receive from healthy ecosystems, including tourism revenue, carbon sequestration, and even increased ocean productivity in some regions. Marine species also have inherent cultural value to the American public and many people want to know that these animals exist, even if they never see them in the wild. Furthermore, many Alaskan Native communities depend on marine mammals for food and cultural continuity and identity. These intertwined benefits provide a strong economic incentive to preserve and conserve marine mammals.

Ecosystem Benefits

Marine mammals play important roles in coastal and ocean ecosystems, from a local to global scale. The benefits of conserving marine species stem in part from the value of the ecosystem services provided by the species.

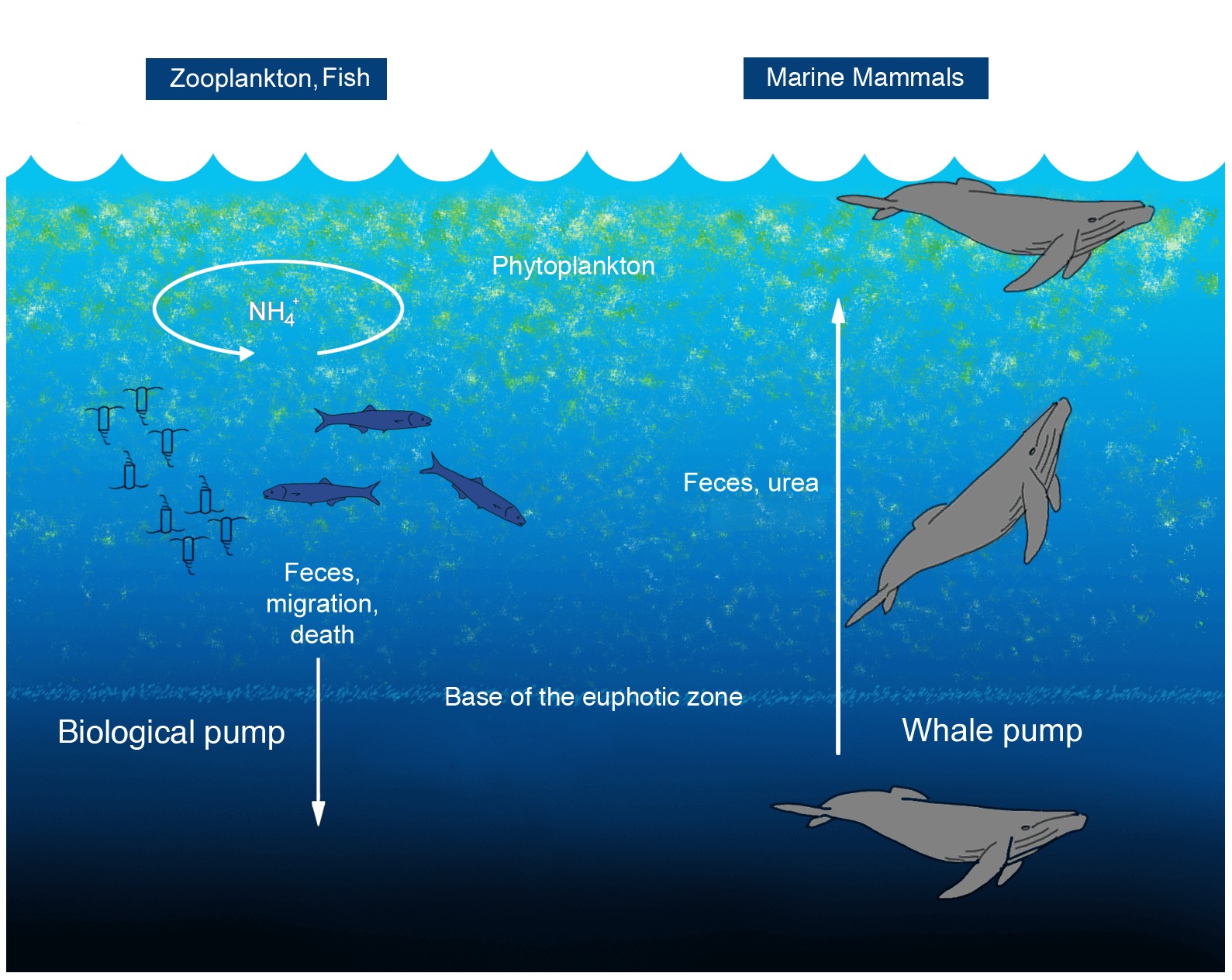

The “whale pump” increases primary productivity (from Roman and McCarthy 2011).

Cetaceans

For example, large whales have been shown to have a role in enhancing primary productivity of marine ecosystems by bringing nitrogen and other nutrients to the ocean surface through their excretions, a process known as “the whale pump.” These nutrients support phytoplankton growth, which provides food for a variety of marine organisms, including marine mammals. The enhancement of primary productivity in coastal waters is a type of ecosystem service that can result in a more productive ocean, which may ultimately increase revenues and employment in the fisheries sector.

Sentinel Species:

While marine mammals play a role in keeping ecosystems healthy, they can also serve as sentinel species, or an early warning system, for when ecosystem health is degrading. For example, organochlorine contaminants like DDT were used for decades and persist in the environment. These compounds accumulate in California sea lions and increase risk of cancer, raising awareness of potential dangers for humans and other animals eating such tainted seafood. Similarly, biotoxins produced by harmful algal blooms (HABs) are associated with marine mammal mortality and also affect human health and food security. A 2022 study found that stomach contents of walruses in the Arctic had biotoxin levels similar to those known to cause illness or death in humans. Understanding marine mammal health helps us evaluate ocean and coastal health, and also its implications for human health and well-being.

Due to its huge size, the carbon stored in a whale’s body can also be important to carbon sequestration. When a whale dies, its carcass can sink and create a “whale fall,” taking the stored carbon within it to the ocean depths. While some of the carcass supports benthic ecosystems, some of the carbon is buried in the sediment, sequestered for millennia. Reducing carbon in our atmosphere is a critical aspect of fighting climate change, something that whales help with in both life and death. The International Monetary Fund estimated the ecosystem services of one whale could be valued at over $2 million, with a combined worth of all large whales estimated at over $1 trillion. Other researchers caution that there are many assumptions which go into such estimates and discussion about carbon credits and climate change policy require further refinement.

Sea Otters

Sea otters, beloved for their fuzzy and charismatic appearance, also make substantive contributions to coastal health. Perhaps the most well-known example is sea otter consumption of urchins, which in turn reduces urchin predation on kelp, allowing kelp forest habitats to thrive, reducing shoreline erosion and promoting biodiversity. However, sea otters are proving to be important to other habitats as well – in some parts of British Columbia sea otters dig for clams in seagrass beds, creating disturbance that promotes seagrass reproduction and enhanced genetic diversity. In Elkhorn Slough, California, ecosystem effects of predation on crabs by recovered sea otter populations have resulted in healthier seagrass beds and greater resilience against human-caused nutrient loading of Elkhorn Slough. Sea otter presence promotes healthy and resilient eelgrass beds, which, like kelp forests, are important nearshore habitats and key to preventing shoreline erosion and sequestering carbon. Eelgrass beds also serve as habitat for diverse species, including a nursery environment for commercially valuable finfish (e.g., salmon and rockfish).

A sea otter swims in amongst eelgrass (Photo: Joe Tomoleoni/USGS).

Contributions to Coastal Economies and Ecotourism

Marine mammals also serve an economic role by attracting tourists and associated revenues in coastal economies.

Whale watchers in Stellwagen Bank observe a humpback whale (Photo: Anne Smrcina/NOAA).

Marine mammal viewing in the wild is part of the lucrative ocean-based tourism and recreation industry. The most recent available data (NOAA 2018) reports a coastal tourism and recreation contribution of $143 billion GDP to the national economy, out producing GDP contributions from commercial ($67 billion) and recreational ($41 billion) fisheries combined ($108 billion) the same year. In 2012, the whale-watching industry generated approximately 2 billion dollars in revenue and supported roughly 13,000 jobs worldwide. Recent location-specific analyses show the importance of whale and dolphin watching and ecotourism to coastal communities. A 2020 study conducted by the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary reported that whale watching contributed $76 million in labor income and $182 million in sales annually to the sanctuary and surrounding community. On the other side of the country, a NOAA-funded study found that whale watching in 2019 supported 850 jobs and $23.4 million in labor income for the state of Alaska. Southern Resident Killer Whale viewing in San Juan County, Washington, contributes over $12 million in state revenue and 1,800 jobs. In Bali, Indonesia, dolphin watching attracts at least 37,000 tourists per year, supports above-average incomes for tour boat operators, and generates substantial profits for local businesses. Ecotourism has thus become a vital contributor to many coastal economies and has fostered public appreciation for marine wildlife while simultaneously providing local communities with a long-term source of jobs and revenues.

In addition to economic benefits, marine mammals can also present economic conflict through fisheries interactions like competition for prey. Marine mammals sometimes engage in depredation, or the removal of bait or catch from fishermen’s lines or nets, resulting in losses for the fishermen. In southeast Alaska, fishermen catching urchins, clams, and crabs have voiced concerns that sea otters are reducing their catches by consuming these species as part of their regular diet. The impact of fisheries taking the prey of endangered Steller sea lions in Alaska or Southern Resident Killer whales in Washington has long been a concern and controversy. Read more about fisheries interactions and bycatch, and policies and efforts to resolve these conflicts.

Marine mammals also help to drive business in educational, public-display facilities such as aquariums and zoos. In 2016, over 90 million people in the U.S. paid an average admission price of $22 to visit institutions accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums that housed marine mammals. In a 2018 survey, AZA-accredited institutions contributed more than $22.5 billion to the U.S. economy and supported 198,000 full-time jobs, a reflection of the value of being able to see and learn more about marine mammals, and wildlife in general, in the United States.

Marine mammal viewing in the wild must be done with care, as it can lead to unintended ecological consequences for certain species. For example, dolphin-watching tours in Hawaii that target resting spinner dolphins may be compromising the health of individual dolphins as well as the population as a whole. This issue was discussed at length during the Commission’s 2019 annual meeting in Kona. Strong support was voiced from numerous stakeholders, including tour operators, for the establishment of minimum approach distances to spinner dolphins and area closures for swimmers and vessels during critical spinner dolphin resting hours. Learn more about these protections on the NMFS website.

A spinner dolphin leaps out the water (Photo: NOAA).

Cultural Significance

Many Americans support actions to protect our oceans and coasts and preserve biodiversity, including marine mammals.

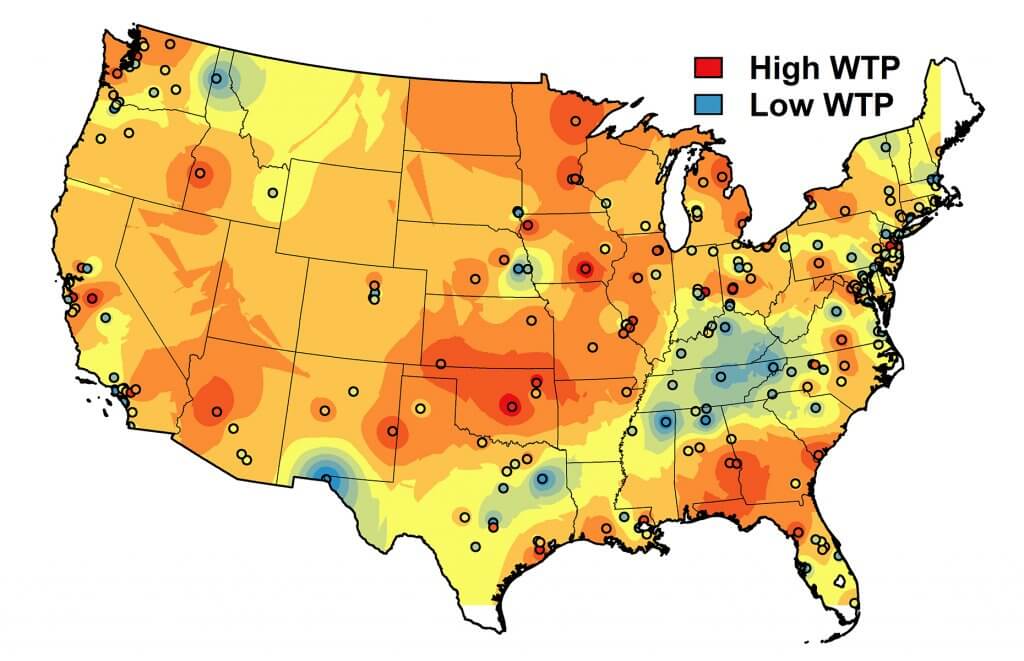

Willingness to pay (WTP) values for recovering the endangered Hawaiian monk seal have been found to vary spatially across the U.S., with areas of high WTP values being found in both coastal and inland areas of the country (map adapted from Johnston et al. 2015 by D. Jarvis, Clark University)

A 2011 study focused on public willingness to pay to “down-list” or “delist” species listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act. Three endangered marine mammal species found in U.S. waters were included in that study—the North Atlantic right whale, North Pacific right whale, and Hawaiian monk seal. The study estimated that U.S. households are willing to pay an average of $71.62 and $73.16, respectively, for the recovery of the two right whale species, and $66.31 for the recovery of Hawaiian monk seals. A case study in Florida found residents of Citrus County were willing to donate an average of $10.25 a year to protect the manatees in their county, and that the manatees contributed ~$8.2 million to the county in tourism-related and ecosystem services value. This type of study builds our understanding of people’s perspectives regarding the inherent value of recovering marine species as we seek to balance the costs and benefits of conserving marine species with the economic needs and values of coastal communities.

A NOAA monk seal volunteer takes notes (Photo: NOAA Fisheries).

Americans who have grown up on the coast watching marine mammals may have an emotional investment in the survival of species associated with a geographic location and ecosystem, as part of the human connection to the environment referred to as a “sense of place.” These connections are evident through various citizen-science groups across the country, dedicated to observing and protecting marine mammals, such as Gotham Whale in New York City, or the Hawaiian monk seal volunteers in Hawaii.

Cultural and social values are an important consideration in marine mammal conservation. The North Atlantic right whale, for example, has a long and difficult history of co-existence with humans. The right whale was aggressively hunted by European and early American whalers, and by the end of the 19th century the population was severely depleted. The right whale was hunted for oil which helped to fuel the Industrial Revolution and American economy at the expense of the species’ population health. The potential extinction of a species like the North Atlantic right whale from the threats of fishing gear entanglement and ship strike would be a loss on many fronts, including disruption to ecosystem health and a reduction in biodiversity. But it would also represent a loss in our centuries old history of human-whale interactions and a failure to recover a species decimated by the quest for economic gain.

Marine Mammals and Alaska Native Peoples

Kaktovik residents starting to cut up a bowhead whale on September 5, 2012 (Dania Moss)

Food Security and Sovereignty:

The Inuit Circumpolar Council Alaska (ICC) has published reports outlining the importance of food security and food sovereignty in the Arctic. To Alaska Native peoples, the two concepts are inextricably linked as expressed in the ICC’s report on food security: “the natural right of all Inuit to be part of the ecosystem, to access food and to care-take, protect and respect all of life, land, water and air. It allows for all Inuit to obtain, process, store and consume sufficient amounts of healthy and nutritious preferred food – foods physically and spiritually craved and needed from the land, air and water, which provide for families and future generations through the practice of Inuit customs and spirituality, languages, knowledge, policies, management practices and self governance. It includes the responsibility and ability to pass on knowledge to younger generations, the taste of traditional foods rooted in place and season, knowledge of how to safely obtain and prepare traditional foods for medicinal use, clothing, housing, nutrients and, overall, how to be within one’s environment. It means understanding that food is a lifeline and a connection between the past and today’s self and cultural identity. Inuit food security is characterized by environmental health and is made up of six interconnecting dimensions: 1) Availability, 2) Inuit Culture, 3) Decision-Making Power and Management, 4) Health and Wellness, 5) Stability and 6) Accessibility. This definition holds the understanding that without food sovereignty, food security will not exist.”

Marine mammals hold strong cultural and social significance to Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and Native Americans who have long histories of sharing coastal landscapes with marine mammals – the archaeological record shows these histories stretch back thousands of years. In addition, marine mammals hold a significant place in the Arctic Indigenous worldview and Alaska Native communities rely on them for food and cultural identity, including the creation and selling of handicrafts and clothing. The MMPA recognizes the importance of traditional hunting and cultural practices involving marine mammals by Alaska Natives. Alaska Native Organizations (ANOs) have partnered with federal agencies to ensure that hunting of marine mammals by their member communities is sustainable and contributes to knowledge of the species and their importance to Alaska Native communities, under a process known as “co-management.” Nine ANOs currently maintain marine mammal co-management agreements with Federal agencies. Those agreements are guided by the recognition that the best way to conserve marine mammal populations in Alaska is to provide full and equal participation by Alaska Natives in decisions affecting the subsistence management of marine mammals.

Conservation of marine mammals in Alaska is important not only to the continuation of traditional lifeways and cultural identities to Alaska Native peoples, but as an essential component of Alaska Native food sovereignty and food security. While definitions of food sovereignty and food security are culturally-specific, they can be generally described as “the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and the right to define their own food and agriculture systems” and “when all people, at all times, have physical, social and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life,” respectively.

The value that marine mammals represent to Alaska Native and other Indigenous societies cannot be concisely calculated or described. Assigning a dollar value to a walrus, for example, neither accounts for, nor accurately describes, the interconnectedness of different dimensions of lifeways, cultural identity, and environmental, nutritional, and cultural health embodied by the walrus.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

General Information

Whale Watching Handbook. International Whaling Commission.

Nature’s Solution to Climate Change. R. Chami et al. 2019. Finance and Development.

Alaskan Inuit Food Sovereignty Initiative. Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska

Inuit Food Security Project. Inuit Circumpolar Council-Alaska