Large Whales and Vessel Strikes

Blue whale diving near container ship (John Calambokidis, Cascadia Research, via NOAA)

Why are large whales at risk and what can be done to help them?

Large whales are vulnerable to being struck and killed or injured by vessels of all sizes. This is an issue of great concern to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Congress, the media, and the public, especially when it involves endangered whale populations or impacts the operations or safety of mariners. It is important to understand how much of a threat vessel strike is to large whales and what options can effectively reduce the risk of injury and death.

Whale behavior can increase their risk of vessel strike

People often wonder why whales don’t simply move out of the way when vessels approach. High levels of ocean noise and the fast speed of some vessels may complicate vessel avoidance. The biology and behavior of each whale species can also affect its risk of vessel strike, highlighting the need for speed or routing measures that specifically address the needs of vulnerable species in particular regions.

North Atlantic right whales

North Atlantic right whales are harder for mariners to see than most whale species because they do not have a dorsal fin. Mothers and calves spend a lot of time resting and nursing near the surface, increasing their vulnerability to vessel strike. Right whales feeding just below or at the surface are also at a higher risk of vessel strike.

Rice’s whales

Tagging studies have shown that Rice’s whales spend up to 88% of their time at night within 15 meters of the surface. This behavior puts them at a high risk of being struck at night.

Is vessel strike a big threat to whales?

Even though whales are large animals, collisions with boats of all sizes can injure and kill them. In the U.S., vessel strike has been identified as a major threat to many large whale species, including North Atlantic and North Pacific right whales, Rice’s whales, blue whales, humpback whales, gray whales, and fin whales.

How do we learn about vessel strikes?

Information regarding vessel strikes is obtained when mariners or others observe and report a vessel strike event, a floating or beached whale carcass, or an injured whale. Vessel strikes can kill or injure large whales in two ways. Blunt force trauma, which occurs when the whale is hit by the bow or hull of a ship, is often not apparent on intact stranded whales but is detected by internal examination after death. Signs of blunt force trauma include bruising and hemorrhage in the blubber and muscle and broken bones. If a carcass is too decomposed, scientists may not be able to detect signs that a vessel strike occurred. Acute trauma, when a whale is hit by the propeller of a vessel, often results in a series of parallel lacerations that can usually be seen by external examination of a carcass or live whale, as seen in the photo below. Analysis of the wounds can help estimate the size of the vessel that was involved in the collision.

Right whale swimming offshore of South Carolina on Jan. 20, 2011 with propeller wounds across its back. The whale has not been re-sighted since. Credit: EcoHealth Alliance (NOAA permit #594-1759).

Because not all deaths are observed (for example, when a whale is struck offshore and the carcass sinks rather than washing up onshore), scientists use the term cryptic mortality to refer to whale deaths that go undetected. The percentage of undetected deaths due to vessel strike can vary between species depending on distribution and monitoring frequency. For example, North Atlantic right whales are found close to shore, are frequently monitored, and healthy right whales are fairly robust, making them more likely to float after death. Despite these factors increasing the likelihood of detection, approximately 64% of right whale deaths by whatever cause are never observed. Cryptic mortality of other large whale species is likely much higher.

What options are there to reduce the risk of a strike?

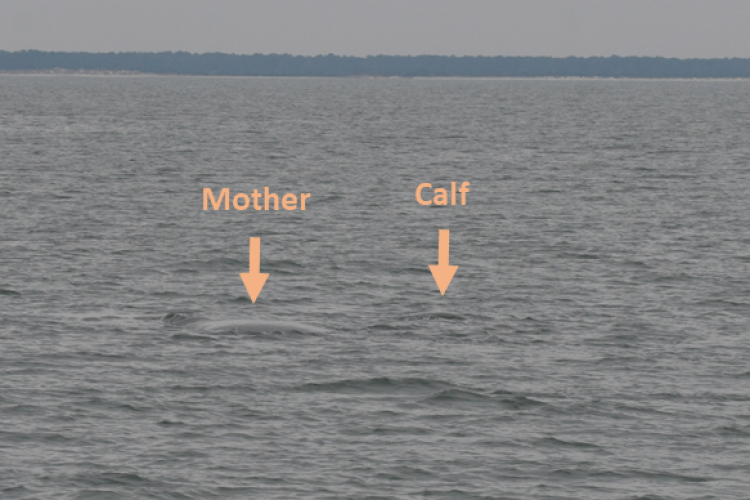

North Atlantic right whales can be difficult for mariners to see because they have no dorsal fin. Mother-calf pairs also spend a lot of time resting at the surface, increasing their risk of vessel strike. (NOAA Permit #594-1467-02)

Depending on the specific needs and behavior of the species at risk, the pattern of vessel traffic, and the areas of highest risk, several options can help reduce the risk of vessel strikes in U.S. waters: Traffic separation schemes and routing measures, Areas To Be Avoided, and Speed Limits.

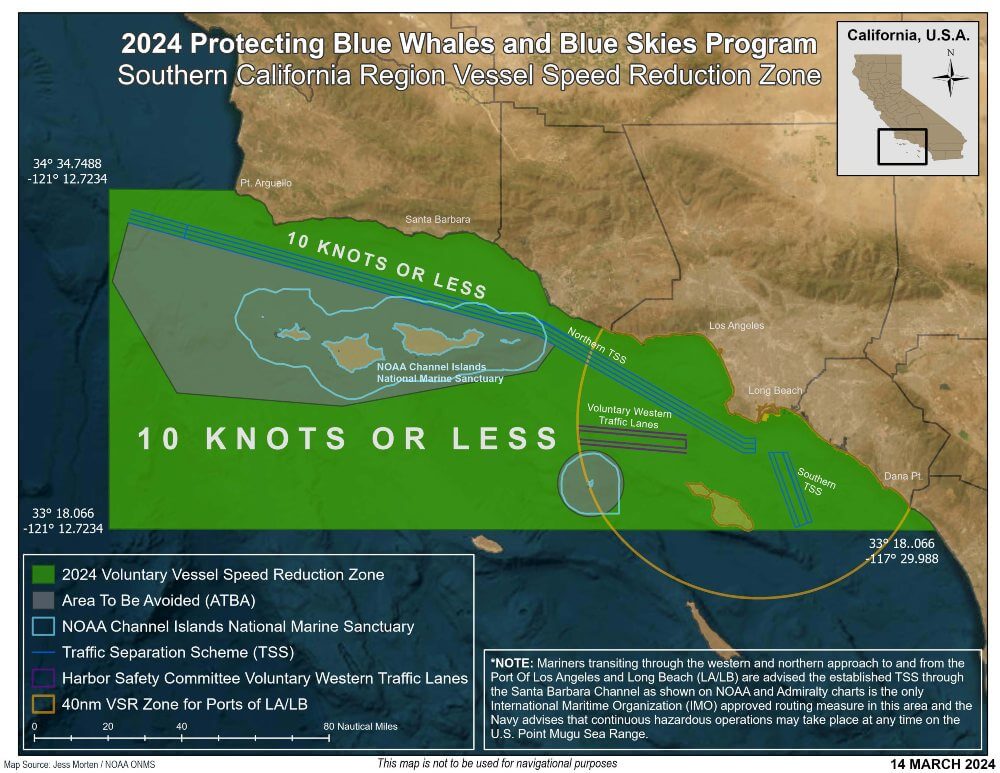

Examples of Vessel Speed Limits, Areas To Be Avoided, and traffic separation schemes are seen along the coast of Southern California (Jess Morten, NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries).

Traffic separation schemes and routing measures are measures that require an analysis of whale distribution and movements, vessel traffic patterns, and navigational hazards. Once a route has been identified that reduces the potential for overlap between whales and vessels, the proposed new routing is considered through a public review and comment process that is initiated by the U.S. Coast Guard, in consultation with NOAA. Once the proposed measures have been adopted domestically, they are taken to the International Maritime Organization (IMO) for review and final approval. The new shipping lanes or routes are then incorporated into navigational charts and advisories for both foreign and domestic vessels traversing U.S. waters.

Areas To Be Avoided are areas that require special protections from vessel traffic due to frequent and persistent use by large whales. Once identified, they go through a similar public review and approval process, by the U.S. Coast Guard and then IMO, as routing measures. They can apply to all or certain classes of vessels, can be voluntary or mandatory, and can be implemented year-round or seasonally. Informal areas to be avoided can also be identified and implemented in U.S. waters outside of the formal U.S. Coast Guard and IMO process.

Vessel speed limits can be voluntary or mandatory and implemented in specific places of high vessel strike risk year-round, seasonally, at certain times of day, or as needed when whales are present. Studies have shown that 10-knot speed limits are the most effective in reducing risk of vessel strike mortality and serious injury of large whales. Exceptions to the speed limits are permitted as necessary to ensure human safety and safety of navigation.

Are small boats part of the problem?

Yes, small boats can also injure and kill whales, especially calves. In fact, five of the 12 North Atlantic right whale deaths in U.S. waters that were caused by vessel strike from 2008-2022 were caused by vessels smaller than 65 feet in length.

Do vessel strike reduction measures prioritize whales over human safety?

Human safety and safety of navigation are always a top priority. Vessel speed rules implemented on the U.S. East Coast to reduce strikes of North Atlantic right whales, for example, allow deviations from the 10-knot speed limit whenever situations or conditions threaten human or navigational safety. It should be noted, however, that speed limits, especially for smaller vessels, may actually increase human safety. For example, in cases when small boats have struck North Atlantic right whales, the vessel operators often did not see the whale prior to the strike, or if they did, it was too late to avoid a collision. Collisions at high speeds can damage vessels and cause serious or fatal injuries to the people onboard.

Where have vessel strike reduction measures been implemented?

U.S. East Coast

A North Atlantic right whale and cargo ship (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission).

After Canada implemented routing measures in the Bay of Fundy in 2003, NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard implemented recommended routing for vessels traveling through important right whale habitats in Cape Cod Bay and near ports in Georgia and Florida in 2006. In the following years, with approval from the IMO, the shipping lanes into and out of Boston were shifted further north to reduce overlap with whale foraging grounds. The IMO also designated the Great South Channel, off of Cape Cod, as a voluntary Area to be Avoided from April through July.

NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) adopted vessel speed measures in 2008 to reduce vessel strikes of North Atlantic right whales. The rule requires that vessels 65 feet and longer travel at speeds no greater than 10 knots when transiting designated seasonal management areas (SMAs). SMAs are only active in certain places and times of year when right whales are present. At the same time, NMFS implemented a separate dynamic management area program that would allow for voluntary speed restrictions to be established in areas and at times when right whales are detected outside of active SMAs. In 2022, after reviewing the data on right whale vessel strikes, NMFS proposed changes to the vessel speed rule to provide greater protections. Those changes included replacing the SMAs with five Seasonal Speed Zones, expanding the rule to include vessels between 35 and 65 feet in length, making speed limits in dynamic speed zones mandatory, and enhancing data collection in support of safety deviations.

Final action by NMFS on the proposed amendments is still pending.

U.S. West Coast

In 2013, recommendations made by the U.S. Coast Guard and NOAA prompted the IMO to shift shipping lanes off San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Long Beach into areas with less overlap between vessels and large whales. In addition, the NOAA Office of National Marine Sanctuaries established voluntary speed reduction zones from May through December. During those times, vessels 300 gross tons and larger are requested to travel 10 knots or less. The vessel speed reduction zones now include the traffic separation schemes off San Francisco and southern California, the Greater Farallones, Cordell Bank, and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuaries, and an expanded Area to be Avoided that encompasses the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and adjacent waters.

Alaska and the Arctic

Humpback whale in Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska. (Christine Gabriele, Glacier Bay National Park).

Although not specifically developed to address vessel strikes of large whales, the U.S. Coast Guard and the IMO adopted voluntary routing measures, including recommended routes, precautionary areas, and Areas to be Avoided in the Bering Strait and Bering Sea in 2017. The U.S. Coast Guard is currently developing similar routing measures for the Arctic Ocean, north of the Bering Strait. In response to the U.S. Coast Guard’s 2018 request for information, the Commission recommended routing measures and vessel speed restrictions in the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas that would decrease the risk of vessel strikes of large whales that migrate through the Bering Strait, along the western Alaska coast, and Barrow Canyon. The Commission recommended also that vessels avoid the Hanna Shoal area in the Chukchi Sea, a summer foraging area for walruses. In Southeast Alaska, vessel speed measures are in place in Glacier Bay National Park to reduce the likelihood of vessels striking humpback whales.

International

Vessel strike reduction measures are not unique to the United States. Other countries, including Canada and Panama, have implemented similar measures to protect marine mammals. Vessels also have been requested to transit further offshore around the southern coast of Sri Lanka in order to reduce the risk of vessel strikes for blue whales. Voluntary mitigation measures also have been established in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea. In 2024, Greece committed to establishing a monitoring and early warning system that detects whales in real-time and urges ships to slow down or change course to avoid collisions.

Have vessel strike reduction measures been successful?

Vessel strike reduction measures, including speed limits, have been successful in reducing the likelihood and lethality of vessel strikes of large whales. On the East Coast, the vessel strike mortality rate of right whales decreased from 10 deaths in the 10 years prior to implementation of the rule to four deaths in the 10 years after the rule was implemented. There was an apparent increase in the number of serious and non-serious injuries after the rule was implemented; however, this may have been influenced by increased reporting during that time. On the West Coast, vessel strike reduction efforts may have reduced vessel-strike mortalities by 9 to 13%.

The success of vessel strike reduction measures depends on operator compliance, which has been a challenge. Compliance with voluntary measures has been low, and in some areas on the West Coast, resulted in little to no reduction in the estimated vessel strike mortality. Mandatory measures have achieved up to 88% compliance on the East Coast, and incentive measures have achieved 78% compliance on the West Coast. Ensuring compliance with, and ultimately the effectiveness of, future measures is essential to reducing injury and mortality.

A blue whale surfacing in the North Atlantic ocean during a NOAA research cruise (NOAA Fisheries Permit No. 779-1633).

What about technologies to detect whales?

Aerial and vessel-based surveys and passive acoustic monitoring technology are used to identify and track the presence of large whales. In some cases, these technologies can detect whales in near real-time and it is possible to alert mariners to their presence. Additional technologies, including satellite detection and thermal imagery, are being developed to further enhance whale detection capabilities. NOAA’s ASTER^3 program was recently established to advance the conservation and recovery of protected species through innovative technology.

Scientists use drones to drop tags on North Atlantic Right Whales (Ocean Alliance/Chris Zadra, NOAA Fisheries Permit #24359).

Each tool has limitations, so managers will likely use a combination of tools to build whale detection capability as these new technologies advance. For example, visual surveys only detect animals near the surface and rely on observer presence and good weather conditions, while passive acoustic monitoring can detect whales subsurface when observers are not present, but requires whales to be vocalizing. Multiple technologies, used in combination with traditional vessel strike reduction measures, will likely be the most effective way to reduce the risk of vessel strike to large whales.

How will climate change affect risk and the effectiveness of reduction measures?

Climate change and warming ocean temperatures can cause shifts in the distribution of marine mammals and their prey. As marine mammals move into new areas without established protections, they may be at a higher risk from human activities. This phenomenon was observed as North Atlantic right whales moved into the Gulf of St. Lawrence in search of their copepod prey. Following that shift in whale distribution, increases in vessel strike mortalities were observed. Similar situations are likely to continue occurring in the future. We need to ensure that marine mammal monitoring programs and modelers have the capacity to detect or predict these changes in distribution as early as possible, and that managers are able to quickly and adaptively implement and amend protection measures as necessary.

LEARN MORE

General Information

IWC – Ship Strikes: collisions between whales and vessels

NOAA Fisheries – Reducing vessel strikes to North Atlantic right whales

NOAA Fisheries – Vessel strikes

MMC – Federal agency approaches to reducing vessel strike of cetaceans webinar

NOAA Fisheries – Vessel Information Fact Sheet

NOAA Fisheries Background Paper on North Atlantic Right Whale Vessel Strikes