Atlantic Humpback Dolphin

Sousa teuszii

Endangered

Depleted

Marine mammal bycatch refers to any marine mammal adversely affected as a result of being unintentionally entangled, entrapped, or caught by nets, lines, traps, or hooks, or otherwise impacted by fishing gear. Bycatch is the greatest direct cause of marine mammal injury and death in the United States and around the world. Sections 118 and 101(a)(5)(E) of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) requires the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) to address marine mammal bycatch through science, gear research, and restrictions on fishing gear and practices.

National Bycatch Strategy

NMFS has developed priorities and strategies for reducing fisheries bycatch at the national level, as part of its 2016 National Bycatch Reduction Strategy, which exists to support sustainable fisheries and the recovery and conservation of protected species. Those priorities and strategies include the following:

Comments submitted by the Commission on NMFS’s National Bycatch Strategy are listed under “Learn More”.

The federal management framework for monitoring and mitigating bycatch is based on assessment of the ability of marine mammal populations to sustain human-caused impacts (the sustainable ‘potential biological removal’ level, or PBR, of each stock), estimation of the numbers of animals seriously injured or killed, and take-reduction efforts based on structured consultations among fishery managers, scientists, conservationists, and fishermen on NMFS’s take reduction teams (TRTs). The Commission is an active member of each of the five recently active TRTs. The Marine Mammal Commission’s 2014 Priorities Report underscored the need for regular stock assessments for marine mammal species that are affected by bycatch. Enabling such assessments requires increased observer coverage within and across fisheries to ensure estimates of bycatch are reliable and up to date. Observed bycatch is typically a fraction of the deaths and serious injuries that actually occur so it is extrapolated to estimate the total for the entire fishery. However, many deaths go undetected because fisheries are unobserved, or would be undetected even if observers were onboard the fishing vessels. These unobserved and undetected deaths are sometimes referred to as ‘cryptic mortality’. For example, roughly two-thirds of all North Atlantic right whales deaths go undetected. The Commission has provided presentations on marine mammal cryptic mortality at two NMFS workshops to address the problem of fully accounting for deaths that are not accounted for through observer data or strandings.

Hooked false killer whale from the Hawaii long-line fishery. (Eric Forney, NOAA PIRO)

One way the Commission works toward reducing bycatch globally is through its grants and research program. In recent years (2018–2023), the Commission funded ten research projects addressing marine mammal bycatch. The Commission also regularly engages with Congress on the science and policy decisions related to marine mammal bycatch. For example, in 2016, the Commission co-hosted with the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) a Congressional briefing to increase awareness of the impacts of marine mammal bycatch at national and international levels. The Commission is also looking for ways to create economic incentives for reducing marine mammal bycatch. In September 2015, the Commission co-hosted an international workshop on incentive-based fishery bycatch measures with the NMFS. This workshop focused on incentives such as individual transferable bycatch allocations to provide greater flexibility to fishing vessel operators to reduce their marine mammal bycatch in a more cost-effective manner. In 2019, the Commission helped plan a workshop that examined economic aspects of bycatch, including how economic mechanisms can incentivize bycatch mitigation, as part of NMFS’s National Bycatch Reduction Strategy.

At the 2017 Biennial meeting of the Society for Marine Mammalogy, the Commission co-organized and co-funded a one-day international workshop on marine mammal bycatch along with WWF and NMFS. In presentations and panel discussions, workshop participants highlighted creative tools to address the challenges of data-poor, open-access, small-scale fisheries. Incentivizing measures such as market access and economic alternatives were also raised as alternative solutions for a wide variety of fisheries. The workshop report, which covers this and two other workshops on marine mammal bycatch during the meeting, can be found here.

Multilateral and regional organizations such as the FAO Committee on Fisheries and Regional Fishery Management Organizations, respectively, are key institutions in addressing global fishery bycatch. At the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission Working Party on Ecosystems and Bycatch, Marine Mammal Commission-funded scientists were able to draft an Executive Summary for cetaceans that occur in the region, where limited data suggest that bycatch interactions in coastal gillnet fisheries may be more common than previously recognized.

At the Commission’s 2019 Annual Meeting one session explored the factors affecting bycatch of odontocetes (dolphins and toothed whales) in a variety of hook-and-line fisheries in and around the Hawaiian Archipelago. At the Commission’s 2023 Annual Meeting, the closing session title, “Whales on the Brink”, considered the substantial threats facing to North Pacific and North Atlantic right whales, including entanglement in fishing gear.

Take Reduction Teams (TRTs) around the United States review and recommend specific bycatch reduction measures for particular fisheries (e.g., Atlantic pot/trap, California drift gillnet, Hawaii shallow- and deep-set longline) through a negotiated, multi-stakeholder process. Those measures are reflected in Take Reduction Plans (TRPs) for each fishery or group of fisheries. The TRTs are mandated to work toward the goal of reducing marine mammal bycatch to levels below PBR within six months, and to levels approaching the zero mortality rate goal (defined as 10% of PBR or less) within five years. Not all TRTs have been successful, and the Commission continues to strive for effective measures and their full implementation and enforcement through active participation on all the TRTs. The Commission’s 2015 Annual Meeting included a session examining TRT performance, with a specific discussion of the factors determining successes and challenges in some of the East Coast TRTs.

Learn more about TRTs and the development of take reduction plans.

Mekong river guards of the Cambodian Fisheries Administration burn gillnets removed from within Core protected zones for the Mekong River population of Irrawaddy dolphins. (Peter Thomas, Marine Mammal Commission)

In 2016 the Commission spearheaded a global bycatch reduction initiative that was announced at the 2016 Our Ocean Conference. U.S. government agencies joined the Environmental Defense Fund, The Nature Conservancy, the Natural Resources Defense Council, and the International Seafood Sustainability Foundation to provide $1.7M to enable fishing nations to better monitor and prevent bycatch in global fisheries, supporting sustainable, ecosystem-based fisheries worldwide. The list of projects focuses on technological, policy and legal capacity building. This initiative dedicates $375K to address marine mammal bycatch on a global level. The Commission has the lead in tracking progress on this initiative and reported to the Department of State on ongoing progress on the ten elements of this initiative in preparation for the 2017 Our Oceans Conference.

The International Whaling Commission launched its Bycatch Mitigation Initiative in 2016, with the goal of developing, assessing and promoting effective bycatch prevention and mitigation measures worldwide. The Marine Mammal Commission nominated several independent scientists to the Initiative’s Expert Panel, all of whom were appointed. In 2023, one of the Commission’s staff members was appointed to the Expert Panel.

Hooked false killer whale from the Hawaii long-line fishery. (Eric Forney, NOAA)

Reliable bycatch data are critical to develop policy measures aimed at reducing the impacts of fisheries on marine mammals. Elements needed to accurately assess and mitigate the impacts of bycatch on marine mammals include:

In many cases, the insufficiency of resources for collecting accurate fisheries and marine mammal data has resulted in poor or out-of-date information, particularly those needed to calculate PBR. The uncertainty and inadequacy of data can create a need for measures that are more restrictive than necessary, leading to unwarranted economic losses in commercial fisheries. Studies have shown that a modest increase in resources to support marine mammal data collection can result in more targeted bycatch reduction measures and less impact on the “bottom line” of commercial fishermen. Additional research is needed to better understand the ecological effects of fishing on marine mammals and marine ecosystems, which are even more challenging to define, assess, and mitigate.

In 2014 and 2015 the Commission co-sponsored two workshops with NMFS to look at innovative and cost-effective ways of collecting marine mammal stock assessment data. One workshop, held in October 2014, examined the use of unmanned aerial systems (UASs or drones) to survey marine mammals, and to collect data on body condition and behavior. The second workshop, held in April 2015 focused on the use of passive acoustics deployed on fixed or towed arrays, or housed in floated buoys or autonomous underwater vehicles (gliders), to detect and estimate the density of marine mammals from their calls.

As part of the National Bycatch Reduction Strategy, the Commission assisted NMFS in the planning and execution of a workshop that in October 2019 examined the connections between the economy and bycatch, including that of protected species such as marine mammals. It was clear from the presentations and discussion that bycatch has a number of impacts on the profitability of fisheries, and that the economy has both positive and negative effects on bycatch. A workshop report will be published in 2020.

The Consortium for Wildlife Bycatch Reduction

Commercial fishing operations are the largest cause of human-related injury and death for many marine mammals. The Marine Mammal Commission supports and strives to advance sustainable fisheries practices that minimize the impact to marine mammals and their environment. The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) establishes an extensive research and management framework for assessing and mitigating marine mammal bycatch in commercial fisheries. A key feature of this framework has been the development of take reduction plans developed in consultation with take reduction teams to reduce high levels of marine mammal bycatch. While this process, in most but not all cases, has resulted in considerable progress in reducing marine mammal bycatch, additional scientific and management efforts are needed to address the indirect impacts of fishing on the complex predator-prey dynamics for marine mammals.

2019 Annual Meeting

In Hawaii, as in many places around the world, many odontocetes (dolphins and toothed whales) take bait or catch off fishermen’s hooks (depredation), and are occasionally, accidentally caught themselves. In part, the Commission’s 2019 Annual Meeting focused on this problem, considering the factors affecting this form of bycatch in Hawaii and methods for its mitigation.

Fisheries can have negative or positive impacts on marine mammals, and the reverse is also true. Direct negative impacts on marine mammals include unintentionally injuring or killing them, or intentionally harvesting them. Indirect negative impacts include reducing the availability of, or altering the size or diversity, of their prey. Habitat degradation caused by certain fishing activities (e.g., bottom trawling) can also have an indirect, negative impact on marine mammals that depend on those habitats for food. Conversely, fisheries can have a positive impact on marine mammals by increasing the availability of prey, which can happen directly when fishing gear flushes or concentrates fish, which then are consumed by marine mammals before they are caught by the gear, or indirectly by increasing the abundance of preferred prey, perhaps by reducing the abundance of the prey’s competitors or predators. Marine mammals can have a direct, negative impact on fisheries by removing bait or caught fish from hooks, nets, or traps or mariculture pens (a behavior called depredation), scaring fish away from fishing gear, or damaging or removing fishing or mariculture gear. In some cases, fishermen seeking to protect their gear or, catch or penned fish may harass marine mammals that are interacting with their gear, sometimes, perhaps inadvertently, causing injury or death.

Fishermen sort their catch from an “eliminator trawl” (Rhode Island Sea Grant)

Bycatch is the number one source of direct human-caused death and serious injury to marine mammals worldwide, estimated at over 650,000 individuals each year. Two important publications (see the Learn More section of this page) have highlighted the significant threat that gillnets, in particular, pose to marine mammals around the world. While the United States has made significant progress in reducing the impact of fisheries operations on marine mammals, fishery bycatch remains a serious problem in other countries. In some cases, fishery bycatch threatens to drive species, such as the vaquita in the Gulf of California, to extinction. Although marine mammals can be bycaught in gear being actively fished, they can also be bycaught in lost, abandoned or discarded gear, a phenomenon called ‘ghost fishing.’ One review of 76 publications on this topic found reports of over 1800 cetaceans entangled in ‘ghost gear’. While the United States is a leader when it comes to sustainable fisheries management, over 90 percent of the seafood we consume is imported. For this reason, the Commission supports regulations by the National Marine Fisheries Service that fully implement Section 101(a)(2) of the MMPA requiring import bans on seafood caught in foreign fisheries whose bycatch injures or kills marine mammals in excess of U.S. standards.

In some fisheries, marine mammals are known to remove catch or bait (depredation) regularly from fishermen’s lines or nets, and some species (primarily pinnipeds) take fish from mariculture pens. Over thirty species of odontocetes are known to engage in depredation. For example, some individuals in populations of sperm, killer, false killer, and pilot whales around the world have become adept at removing a variety of fish species from longline hooks, a behavior also exhibited by other toothed whales and dolphins in a wide range of fisheries. Other species have learned to take catch from trawl or gill nets. Unfortunately, depredating marine mammals occasionally make a mistake and are hooked or trapped, which can result in serious injury or death.

Steller sea lions range along the North Pacific Rim from northern Japan to California. (NOAA’s National Marine Mammal Laboratory)

Depredation can significantly affect the volume and quality of catches, and therefore profits, lead to fishermen taking potentially deadly retaliatory actions, and increase the likelihood of entanglement or hooking of marine mammals. The Commission is working with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and other partner agencies to better understand impacts of depredation on marine mammals and find possible solutions, such as through the development of non-lethal deterrents aimed at minimizing interactions between marine mammals and fishing gear. In early 2018, NMFS increased the threat categorization of a sablefish longline fishery in the Gulf of Alaska because of the potential for depredating sperm whales to be caught and seriously injured or killed (see Commission letter commenting on this action).

In December 2014, NMFS sought comment on their intent to prepare national guidelines for the use of marine mammal deterrents (e.g., acoustic scaring devices, electrical wires, water jets, rubber bullets) that would not cause serious injuries or death. In response, in its recommendations the Commission emphasized the importance of clearly distinguishing between serious and non-serious injuries, using deterrents only when warranted, and preventing unrestricted use of noisemakers. To assist NMFS in its efforts, a Commissioner and Commission staff member attended a NMFS-hosted workshop in 2015 addressing non-lethal marine mammal deterrents for fishery operators as well as others impacted by recovering species. NMFS published a proposed deterrents guidelines in August 2020, but as of April 2021, the agency has yet to issue the final deterrent guidelines, nearly over six years after seeking public comment. In 2017, the Commission provided funding via its grant program to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution to characterize depredation in Northeast U.S. sink gillnet fisheries.

Several reviews of depredation occurring in a wide variety fisheries around the world have found that deterrents such as explosives and acoustic deterrent devices (ADDs) are largely ineffective. Changes in fishing gear (e.g., hook protectors or stronger traps) and practices (e.g., avoiding some areas or moving when depredation occurs) have proven to be much more effective.

The Commission works with the False Killer Whale Take Reduction Team and NMFS to amend the regulations of the Hawaii deep-set longline fishery to further reduce the likelihood that false killer whales are killed or seriously injured while depredating catch and bait in that fishery. Similarly, the Commission is working with the Pelagic Longline Take Reduction Team to reduce the bycatch of depredating pilot whales and Risso’s dolphins in by the Atlantic pelagic longline fishery to insignificant levels.

Indirect impacts of fisheries operations on marine mammals include competition for prey and damage or destruction of sensitive marine mammal habitat. While these and other indirect effects could be significant, they have received less attention by scientists and fishery managers, in part because of the difficulties in understanding complex marine ecosystems and food webs. Globally, fisheries have significantly reduced the size of many fish stocks and continue to unsustainably exploit them year after year. Removing a large portion of the biomass of a target fish stock may have severe effects on marine mammals and other predators that prey on the stock. In addition, some types of trawl and dredge fishing have been shown repeatedly to significantly alter the physical and biological structure of sensitive marine habitats, potentially affecting marine mammals that depend on those habitats.

Competition between fisheries and marine mammals is an issue in many fisheries. For example, in southeast Alaska, fishermen catching urchins, clams, and crabs have voiced concerns that sea otters are reducing their catches by consuming these species as part of their diet. Also, the impact of fisheries taking the prey of endangered Steller sea lions in Alaska or Southern Resident Killer whales in Washington has long been a concern and controversy. Reduction in key prey species by fishing could compromise the sea lions’ foraging efficiency and, consequently, their ability to survive, grow to maturity, and reproduce at rates sufficient for the population to recover. In part to mitigate this risk, fisheries management in the Aleutian Islands includes measures designed to reduce the fisheries depletion of certain fish stocks in areas of particular importance to Steller sea lions.

The Commission believes that indirect effects of fishing on marine mammal prey resources should be considered when establishing catch limits for fish stocks developed under fishery management plans required by the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act. We have provided recommendations on proposed revisions to NMFS’s Magnuson-Stevens National Standard 1 Guidelines, highlighting some of our concerns regarding the impact of fisheries harvest on marine mammals. In particular, we recommend that the guidelines for determination of “Optimal Yield” adequately incorporate ecological factors, such as the role of the target fish species in the ecosystem, such as forage fish.

Marine mammals can consume substantial amounts of fish, in some cases comparable amounts to that taken by fisheries. It can be tempting to infer that marine mammals must be reducing the availability of fish to fishermen, but demonstrating such a link has proven to be very difficult because of the complexity of marine ecosystems, and because marine mammals are often only taking related species or size classes that are not targeted by fishermen. Similarly, clear demonstrations are lacking that fisheries have reduced marine mammal prey availability to limiting levels. A recent ecosystem simulation study of fisheries and three cetacean species in the Rías Baixas shelf ecosystem (North-West Spain) concluded that intense fishing would reduce the variety of available prey and lead to competition among the cetaceans.

The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s (ASMFC) Menhaden Management Board has developed ecological reference points that take into account the requirements of menhaden predators, such as marine mammals, and that will be used to set ecosystem-based catch targets and limits. In a 24 October 2017 letter, the Commission encouraged the ASMFC to implement the use of ‘rule-of-thumb’ ecological reference points (ERPs) to manage the menhaden fishery until ERPs specific to this fishery can be developed. Stock assessment scientists with the ASFMC and NMFS completed development of the ERPs, and in January 2020 published a stock assessment of Atlantic menhaden using ecological reference points. In August 2020, the ASFMC approved ERPs that take into account the impact of menhaden fishing on striped bass. Although, the impact on marine mammals was found to be minimal, the development of ERPs that account for the needs of predators is an important step forward in fisheries management.

Marine Mammal Bycatch (Marine Mammal Commission)

Fisheries Interaction (NOAA Fisheries)

Marine mammals have long been essential to Alaska Native subsistence, culture and way of life. Recognizing this, Congress included an Alaska Native Exemption in the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) that allows Alaska Natives to take marine mammals for subsistence purposes and for creating and selling authentic native articles of handicrafts and clothing, provided that the take is not accomplished in a wasteful manner.

The 1994 amendments to the MMPA included Section 119 to allow the Secretaries of Commerce and the Interior to “enter into cooperative agreements with Alaska Native organizations to conserve marine mammals and provide co-management of subsistence use by Alaska Natives.” Implicit in Section 119 is the belief that cooperative efforts to manage subsistence harvests that incorporate the knowledge, skills, and perspectives of Alaska Natives are more likely to achieve the goals of the MMPA than is management by the federal agencies alone.

Polar bears feed on unused portions of whale carcasses that are deposited at a “bone pile” at Barter Island, near Kaktovik, during the subsistence whale harvest season. (FWS)

Agreements “may include grants to Alaska Native Organizations for, among other purposes,

ANOs with Co-Management Agreements with NMFS

Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission – bowhead whales

Alaska Beluga Whale Committee – Western Alaska beluga whales (Eastern Bering Sea, Eastern Chukchi Sea, and Beaufort Sea stocks)

Aleut Community of St. Paul Island – Steller sea lions and northern fur seals

Aleut Community of St. George Island – Steller sea lions and northern fur seals

Aleut Marine Mammal Commission – all marine mammal species with particular focus on Steller sea lions and harbor seals

Ice Seal Committee – Alaskan ice seals (including ringed, spotted, bearded, and ribbon seals)

Indigenous People’s Council for Marine Mammals (IPCoMM) – “umbrella” organization that brings together representatives from other ANOs to address issues of common interest

ANOs with Cooperative Agreements with FWS

Alaska Nannut Co-management Council – polar bears (in process of establishing a cooperative agreement with FWS as the successor organization to Alaska Nanuuq Commission, which is no longer active)

Eskimo Walrus Commission – Pacific walruses

Since 1994, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) have entered into agreements with several Alaska Native Organizations (ANOs) involving 11 marine mammal species (see links at right). ANOs are authorized by Tribal leadership to enter into specific co-management or cooperative agreements. The agreements vary in content by species, region, and agency but generally describe harvest monitoring methods; collaboration on research, education, and outreach projects; required funding; means to resolve conflicts; and procedures for terminating the agreement.

In 1997, NMFS and FWS entered into an “umbrella agreement” with the Indigenous People’s Council for Marine Mammals (IPCoMM), which was revised in 2006. The umbrella agreement provides a foundation and a direction for developing co-management agreements between ANOs and federal agencies. IPCoMM was given the authority to enter into this umbrella agreement by authorizing resolutions from the Alaska Federation of Natives and those Tribally authorized ANOs that are members of IPCoMM.

Co-management efforts have integrated the field skills and Indigenous Knowledge of Alaska Native hunters and subsistence users with the scientific and technological expertise of scientists to enhance understanding of marine mammals in Alaska, including their stock structure, status, trends, movement and habitat-use patterns, responses to climate change, animal health and condition, contaminants, and disease. Sampling of Native-harvested animals for scientific purposes (often referred to as biosampling) has provided marine mammal tissues for a variety of studies. Education and outreach efforts co-led by experienced hunters and resource managers reinforce sustainable hunting practices, and familiarize Alaska Native youth with cultural and subsistence traditions. Such efforts contribute significantly to marine mammal conservation and the maintenance of subsistence cultures.

In February 2008, the Commission held a meeting in Anchorage, Alaska, to review co-management, to assess progress of cooperative agreements in conserving marine mammals and providing co-management of subsistence use by Alaska Natives, and to identify ways forward. For more information, see the report Review of Co-Management Efforts in Alaska.

Following up on the Commission’s 2008 review, the Commission undertook a more in-depth review of marine mammal co-management, as recommended by IPCoMM at its 2016 Board meeting. The objectives of the review were to identify essential components and key impediments to effective co-management of marine mammals in Alaska. The overall goal of the review was to strengthen co-management relationships between ANOs and federal partners to improve the conservation of marine mammals in a region where marine mammals provide food security for Alaska Natives and are also of critical ecological, social, and economic importance. The review was funded by the North Pacific Research Board and was conducted in 2018. The review was guided by a Steering Committee of Alaska Natives and federal resource managers from NMFS and FWS, using a “case-study” approach focused on three ANOs — the Eskimo Walrus Commission, the Aleut Marine Mammal Commission, and the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island. More information about the review and its findings can be found on the Co-Management Review Project webpage.

also of critical ecological, social, and economic importance. The review was funded by the North Pacific Research Board and was conducted in 2018. The review was guided by a Steering Committee of Alaska Natives and federal resource managers from NMFS and FWS, using a “case-study” approach focused on three ANOs — the Eskimo Walrus Commission, the Aleut Marine Mammal Commission, and the Aleut Community of St. Paul Island. More information about the review and its findings can be found on the Co-Management Review Project webpage.

The Commission attends co-management meetings and works to facilitate further discussions with federal agencies, ANOs, and communities, as appropriate, regarding how the findings and recommendations from the 2018 review, in addition to other efforts, can be used to continue to enhance co-management and conservation of marine mammals in Alaska.

The Commission supports increased opportunities for Alaska Native participation in marine mammal research and management activities. The Commission’s Grants and Research Program serves as one mechanism to support co-production of science knowledge used in co-management, funding projects that have incorporated Indigenous Knowledge and collaborated with co-management partners to advance the conservation and protection goals of the MMPA. Additionally, the Commission continues to explore ways to engage new generations of Alaska Natives and federal agency staff in co-management activities. For example, the Commission has recently partnered with Alaska Sea Grant’s Community-Engaged Undergraduate Internship Program to sponsor internships with ANOs, providing leadership opportunities and fostering future co-management leaders.

Kaktovik residents harvesting a 44′ bowhead whale in September 2012 (Dania Moss)

The 20-year history of co-management of marine mammals between federal agencies and Alaska Native organizations prompted the Commission to ask whether lessons learned from successful co-management activities could enhance the federal government-to-Tribal government consultation process in Alaska.

Executive Order 13175 directs federal agencies to consult with American Indian and Alaska Native tribes on policies, regulations, legislation, and other actions that may have Tribal implications. This includes actions affecting not only marine mammals but also all other tribal resources (natural, cultural, and socioeconomic). The Commission believes that the existing tribal consultation processes in Alaska could be strengthened to ensure meaningful, timely, and coordinated input by Alaska Native communities on issues involving marine mammals and their availability for subsistence.

In December 2012, the Commission, in collaboration with IPCoMM and the Environmental Law Institute (ELI), convened a meeting to review and seek ways to improve the Tribal consultation process. Participants included representatives of various federal agencies, ANOs, other Alaska Native Tribal members, and public and private stakeholders. Several meeting participants suggested that Alaska Native communities should develop guidance on how the tribes themselves would like federal agencies to conduct consultations related to actions that may affect marine mammals. For more information, see the summary of the Commission meeting on Consultation and Co-Management.

In October 2014, the Commission contracted with ELI to work with IPCoMM, ANOs, and others to develop model procedures for government-to-government consultations with Alaska Native tribes under Executive Order 13175 and related directives. The objective of the project was to assist Alaska Native communities in the development of model consultation procedures regarding policies, regulations, legislation, or other federal actions that have Tribal implications. The model consultation procedures would draw from the experiences and lessons learned from marine mammal co-management and cooperative agreements to improve and strengthen consultations involving Alaska Natives. ELI convened an advisory group with expertise in marine mammal consultation and co-management to help guide the project, with assistance from IPCoMM. The draft procedures were reviewed by Alaska Natives and several federal agencies. ELI issued a final handbook outlining model consultation procedures in January 2016.

In response to a 26 January 2021 Presidential Memorandum on Tribal Consultation and Strengthening Nation-to-Nation Relationships, the Commission reviewed and updated its 2010 Action Plan for the Implementation of Executive Order 13175 regarding Consultation and Coordination with Tribal Governments. The Commission developed its original action plan in 2010 pursuant to President Obama’s 5 November 2009 Presidential Memorandum Concerning Tribal Consultation under the Executive Order. The Commission coordinated its review of the plan in Alaska through IPCoMM. The Commission’s Chairman and Alaska Native Liaison participated in IPCoMM’s 15-16 July 2021 Board of Director’s meeting, at which they gave a presentation and received comments on the revised action plan. Subsequent to that meeting, the Commission sent the plan for comment to all 14 Tribally authorized ANOs and Native villages that are members of IPCoMM and separately to two other Tribal villages at the request of ANOs. In addition, the Commission sent the plan to other ANOs and regional organizations that, although not Tribal entities, represent Alaska Natives on marine mammal issues. In all, the Commission sent the plan to 22 ANOs, Alaska Tribal villages, and Alaska regional organizations for review and comment.

The Commission also sent the action plan to the Makah Tribe in Washington, whose treaty specifically reserves hunting rights for marine mammals. The Commission’s three Commissioners and senior staff met with the Makah Tribe to discuss provisions of the action plan and ways in which it could be strengthened to address the Tribe’s concerns. Although the Commission’s action plan provides for consulting with other treaty Tribes in appropriate situations, the Makah Tribe is the only one that is covered explicitly in the Commission’s action plan.

Based on comments received from the Tribes and ANOs, the Commission made several changes to clarify certain elements of the action plan. The Commission submitted its revised action plan to the Office of Management and Budget in November 2021. A copy of the revised action plan is available here.

The table below provides a list of marine mammal species and populations listed as endangered or threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), or designated as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). The MMPA gives special attention to depleted marine mammal species and populations. Species or populations are considered depleted if they are below their optimum sustainable population level, or are listed as endangered or threatened under the ESA.

Please visit our species of concern page or follow the links below to learn more about our work and what we do to help conserve marine mammals and their environment.

ESA Listing

Evaluation of marine mammals for listing under the ESA is done by either the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (for sirenians, otters, walruses, and polar bears) or the National Marine Fisheries Service (all other species).

MMPA Listing

All marine mammal species are protected under the MMPA; some designated as depleted. Please visit the National Marine Fisheries Service website for more information on MMPA listings.

Atlantic Humpback Dolphin

Sousa teuszii

Endangered

Depleted

Delphinapterus leucas

Endangered

Depleted

Beluga, Sakhalin Bay-Nikolaya Bay-Amur River stock

Delphinapterus leucas

Not Listed

Depleted

Blue whale

Balaenoptera musculus

Endangered

Depleted

Bottlenose dolphin, Western North Atlantic Northern Florida Coastal stock

Tursiops truncatus

Not Listed

Depleted

Bottlenose dolphin, Western North Atlantic Central Florida Coastal stock

Tursiops truncatus

Not Listed

Depleted

Bottlenose dolphin, Western North Atlantic Northern Migratory Coastal stock

Tursiops truncatus

Not Listed

Depleted

Bottlenose dolphin, Western North Atlantic Southern Migratory Coastal stock

Tursiops truncatus

Not Listed

Depleted

Bottlenose dolphin, Western North Atlantic South Carolina-Georgia Coastal stock

Tursiops truncatus

Not Listed

Depleted

Bowhead whale

Balaena mysticetus

Endangered

Depleted

Lipotes vexillifer

Endangered

Depleted

Coastal Pantropical spotted dolphin

Stenella attenuata graffmani

Not Listed

Depleted

False killer whale, Main Hawaiian Islands Insular distinct population segment

Pseudorca crassidens

Endangered

Depleted

Fin whale

Balaenoptera physalus

Endangered

Depleted

Gray whale, Western North Pacific distinct population segment

Eschrichtius robustus

Endangered

Depleted

Hector’s Dolphin, Maui Dolphin subspecies

Cephalorhynchus hectori maui

Endangered

Depleted

Hector’s Dolphin, South Island subspecies

Cephalorhynchus hectori hectori

Threatened

Depleted

Humpback whale, Arabian Sea distinct population segment

Megaptera novaeangliae

Endangered

Depleted

Humpback whale, Cape Verde Islands/Northwest Africa distinct population segment

Megaptera novaeangliae

Endangered

Depleted

Humpback whale, Central America distinct population segment

Megaptera novaeangliae

Endangered

Depleted

Humpback whale, Mexico distinct population segment

Megaptera novaeangliae

Threatened

Depleted

Humpback whale, Western North Pacific distinct population segment

Megaptera novaeangliae

Endangered

Depleted

Platanista gangetica minor

Endangered

Depleted

Killer whale, AT1 population

Orcinus orca

Not Listed

Depleted

Endangered

Depleted

Pacific northeastern offshore spotted dolphin

Stenella attenuata attenuata

Not Listed

Depleted

Eubalaena glacialis

Endangered

Depleted

Eubalaena japonica

Endangered

Depleted

Balaenoptera ricei

Endangered

Depleted

Sei whale

Balaenoptera borealis

Endangered

Depleted

Southern right whale

Eubalaena australis

Endangered

Depleted

Sperm whale

Physeter macrocephalus

Endangered

Depleted

Spinner dolphin, Eastern stock

Stenella longirostris orientalis

Not Listed

Depleted

Taiwanese Humpback Dolphin

Sousa chinensis taiwanensis

Endangered

Depleted

Phocoena sinus

Endangered

Depleted

Bearded seal, Beringia distinct population segment

Erignathus barbatus

Threatened

Depleted

Bearded seal, Okhotsk distinct population segment

Erignathus barbatus

Threatened

Depleted

Guadalupe fur seal

Arctocephalus townsendi

Threatened

Depleted

Neomonachus schauinslandi

Endangered

Depleted

Monachus monachus

Endangered

Depleted

Northern fur seal, Pribilof Island/Eastern Pacific stock

Callorhinus ursinus

Not Listed

Depleted

Ringed seal, Arctic subspecies

Phoca hispida hispida

Threatened

Depleted

Ringed seal, Baltic subspecies

Phoca hispida botnica

Threatened

Depleted

Ringed seal, Ladoga subspecies

Phoca hispida ladogensis

Endangered

Depleted

Ringed seal, Okhotsk subspecies

Phoca hispida ochotensis

Threatened

Depleted

Ringed seal, Saimaa subspecies

Phoca hispida saimensis

Endangered

Depleted

Spotted seal, Southern distinct population segment

Phoca largha

Threatened

Depleted

Steller sea lion, Western population

Eumetopias jubatus

Endangered

Depleted

Amazonian manatee

Trichechus inunguis

Endangered

Depleted

Dugong

Dugong dugon

Endangered

Depleted

West African manatee

Trichechus senegalensis

Threatened

Depleted

Trichechus manatus

Threatened

Depleted

Ursus maritimus

Threatened

Depleted

Marine otter

Lontra felina

Endangered

Depleted

Northern sea otter, Southwest Alaska distinct population segment

Enhydra lutris kenyoni

Threatened

Depleted

Enhydra lutris nereis

Threatened

Depleted

For questions about the marine mammal species and populations listed on the table above, please contact mmc@mmc.gov.

HPAI and Marine Mammals

An ongoing global epizootic caused by a highly pathogenic avian influenza virus (HPAI) is posing serious threats for marine mammals. It has caused massive die-offs of seals and sea lions in South America, smaller epidemics in seals in North America and Europe, and sporadic deaths of dolphins in North America, Europe and South America. Read more from the Commission’s HPAI factsheet, and find a map of the latest detections in mammals in the US on the USDA website.

The health of our oceans, marine mammal, and people are inextricably linked. Similar to humans, marine mammals are long-lived, and often swim in the same coastal waters and eat the same fish or shellfish as people. Like humans, they breathe air, making them vulnerable to aerosolized harmful algal bloom (HAB) toxins and infectious respiratory pathogens. They often feed high in the food web, making them susceptible to ingestion of HAB toxins and the persistent chemical pollutants that magnify through the marine food chain. Increases in reports of diseases in marine mammals have raised concerns that ocean health is deteriorating (Simeone et al. 2015).

Marine mammals are adapted for a life in the ocean, but may strand on shore due to environmental conditions, disease or following death at sea. Investigations of these stranding events increase our understanding of the health of marine mammals and, by their connection to it, the health of the ocean. Understanding these factors is crucial to meeting the Marine Mammal Commission’s primary goal to maintain marine mammals as functioning elements of healthy ecosystems.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (MMHSRP) was established under Title IV of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) and is responsible for coordinating national response to stranded pinnipeds (seals) and cetaceans (whales). The MMHSRP does this through collaborations with federal and state facilities as well as via a volunteer network of regional stranding responders, involving aquaria, academic institutions, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). For more information about reporting a stranded, beached, or injured marine mammal, visit NOAA’s stranding page for hotline information.

Marine Mammal Commissioner and veterinarian, Dr. Frances Gulland, responds to a stranded whale. (The Marine Mammal Center)

The activities and capacities of stranding network member institutions may be supplemented or enhanced through an annual program of competitive federal Prescott grants. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) coordinates responses to stranded manatees, sea otters, polar bears, and walruses.

The Global Stranding Network (GSN) supports international marine mammal stranding response. The GSN assists with strandings of all marine mammal species and works closely with the International Whaling Commission’s Strandings Initiative to share best practices, provide relevant trainings, and increase collaboration and capacity to respond to marine mammal strandings worldwide.

When more than two marine mammals strand at the same time in the same general area it is known as a mass stranding. Mass strandings occur quite frequently in the United States and in Cape Cod, Massachusetts in particular. These strandings involve anywhere from a few, to several hundred animals. Unusual Mortality Events (UMEs) are specifically defined under Title IV of the MMPA as strandings that are “unexpected, involve a significant die-off of any marine mammal population, and demand immediate response,” including scientific investigation.

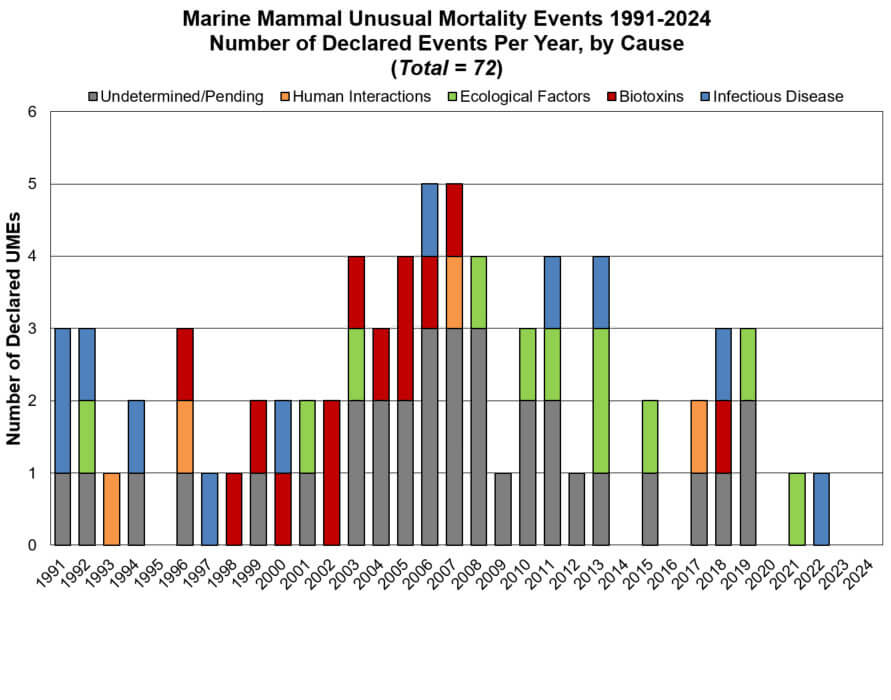

Since the UME program was established in 1991, there have been more than 72 formally declared UMEs across all coasts of the United States. The most commonly affected species are bottlenose dolphins, California sea lions, and Florida manatees and the most common UME causes include infections, human interactions, and biotoxins (poisonous substances produced by living organisms, usually Harmful Algal Blooms, HABs). For more information on UMEs, visit NOAA’s UME Web page.

UMEs between 1991 and 2024, showing the number of declared events and known causes per year. (NOAA)

A bottlenose dolphin in Barataria Bay, LA receives a cardiac ultrasound (National Marine Mammal Foundation).

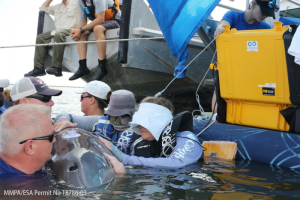

Biosurveillance and baseline health research are also important components of the MMHSRP. Targeted studies of live marine mammals, including capture-release health assessments, visual assessments, photogrammetry, and remote tissue sampling, are used to monitor the health of populations. These health data have been used to assess population trends (Schwacke et al. 2024) and to help to interpret information from UME investigations.

The Commission recognizes the importance of understanding the health of marine mammals as part of healthy ecosystems, and we are committed to supporting a national plan for temporally- and spatially-structured health surveillance, and the development of the Marine Mammal Health Monitoring and Analysis Platform (Marine Mammal HealthMAP).

Stranded juvenile California sea lions recuperating at The Marine Mammal Center in Sausalito. (The Marine Mammal Center)

In December 2022, Congress enacted the James M. Inhofe National Defense Authorization Act, which include the Marine Mammal Research and Response Act (MMRA; pg. 1587). The MMRA instructs NOAA to establish HealthMAP, and to make it publicly accessible through a web portal. The Act also requires that additional data collected from stranding or entanglement events, such as weather and tide conditions, morphometrics, histopathology, toxicology, microbiology, virology, parasitology, and life history data, be collected by NOAA, as available from the stranding network members. These additional data will support modeling and analyses that will improve our understanding of the causes of strandings, and help to identify emerging threats.

Marine mammals around the world face similar threats and conservation challenges and many marine mammals found in U.S. waters range into international waters and into the jurisdictions of other countries. The Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) recognizes that the United States has a vital role to play in the conservation of marine mammals worldwide.

Section 202(a) of the MMPA provides the basis for the Commission’s international work, which includes participating in international negotiations and agreements, and promoting research to further the conservation of marine mammals.

The Marine Mammal Commission works to ensure that threats to marine mammals, particularly those most at risk of extinction, are identified in the United States, in other nations, and on the high seas. We support efforts to understand and reduce these threats in specific countries and through regional and multilateral scientific research and conservation. A major priority is reducing the bycatch of marine mammals in both large- and small-scale fisheries, in particular, calling for and supporting strengthened emergency efforts to eliminate bycatch of vaquitas in fisheries in the Gulf of California, Mexico. The concern over bycatch and other threats carries into our work on endangered populations of coastal and freshwater dolphins in Asia, and safeguarding the health of polar bears and other Arctic marine mammal populations in the face of declining sea-ice and other ecosystem changes brought on by climate change. We work with science and management bodies such as the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and the Arctic Council.

Vaquitas swimming in the Gulf of California. (Chris Johnson)

The MMPA provides a mandate to U.S. agencies, including the National Marine Fisheries Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of State, and the Commission to use existing international agreements and, if necessary, develop new ones to ensure the protection and conservation of marine mammals worldwide. Several provisions of the MMPA are directed explicitly at international threats, such as those that allow the banning of importation of seafood from fisheries that result in serious injury or mortality of marine mammals but are not subject to protection measures “comparable in effectiveness” to U.S. standards.

NOAA International Marine Mammal Conservation

International Whaling Commission (IWC)

IUCN SSC Cetacean Specialist Group

For additional information on the Marine Mammal Commission’s international efforts, see our 2010–2011 annual report and 2012 annual report.

The Arctic marine environment is changing rapidly. The most obvious indicator of such change is the dramatic reduction of seasonal sea-ice, but many other aspects of Arctic marine ecosystems are being profoundly altered. The impacts of these changing environmental conditions on marine mammals may be exacerbated by the rapid changes in human activity that they make possible (e.g., expansion of shipping and offshore energy exploration, mining, commercial fishing, coastal development and tourism).

Scientist listening for real-time sounds of marine mammals and other marine fauna in the Arctic Ocean, Canada Basin. (Jeremy Potter, NOAA/OAR/OER)

Several species of marine mammals are adapted to Arctic conditions and are therefore bound to lose resilience as those conditions change or disappear. Further, Indigenous communities in the Arctic depend on marine mammals for subsistence and cultural identify. The loss of sea-ice is degrading or eliminating important habitat of marine mammals that use sea-ice and snow cover for foraging, resting, molting, reproduction, and refuge from predators (e.g., polar bears, walruses, ringed and bearded seals). The long-term consequences of climate change for other species, including bowhead and beluga whales and seasonal visitors such as gray whales and humpback whales, are less clear. However, virtually all marine mammals are likely to be affected at least indirectly by the rapid ecosystem-level changes that are underway—as a result of warming temperatures, ocean acidification, longer seasons of open water, and thinner sea-ice.

Ribbon seal hauled out on the ice. (Michael Cameron, NMFS)

The opening of new sea routes across the Arctic and increased Arctic shipping is following decreased seasonal ice cover, bringing risk of oil spills as well as ship strikes and disturbance of marine mammals. Management of offshore oil and gas development in the Arctic, must account for the risk of oil spills and possible energy development impacts arising from the sounds generated by seismic testing and drilling operations, possible chemical contamination, alteration of key habitats, and disturbance from vessel and aircraft support activities. It is critical to develop scientific baseline information on marine mammals and their ecosystems across the Arctic against which to assess future impacts and evaluate the effectiveness of mitigation and response efforts. In this light, the Circumpolar Biodiversity Monitoring program under the Arctic Council’s Conservation of Arctic Fauna and Flora working group published the State of Arctic Marine Biodiversity Report in May 2017, during the final Arctic Council Ministerial under the U.S. Chairmanship. This report, which was updated in 2021, provides detailed baseline information on status and threats to Arctic marine mammals.

Unique among federal agencies, the Commission is also responsible for recommending provisions that ensure the availability of marine mammals for Alaska Native subsistence and cultural purposes. Accordingly, the Marine Mammal Commission has a longstanding commitment to support the assessment of marine mammal stocks and the management of risks to marine mammals and subsistence communities in a changing Arctic.

State of Arctic Marine Biodiversity Report, 2020

Arctic Research Plan 2022-2026

Co-Management and Alaska Native Tribal Consultation

For additional information on the Marine Mammal Commission’s efforts in the Arctic, see our 2012 annual report.

Oil platform located 10 km off the coast of central California near Point Conception near gray whale migration route. (NASA)

Worldwide demand for energy from all sources is increasing, and a significant portion of that energy comes from the marine environment. The development of offshore energy resources can impact various components of the marine environment, but our understanding of those impacts and our ability to mitigate them effectively to prevent harm to marine mammals lags behind advances in energy development. Reducing our dependence on foreign energy sources is a critical goal for the United States, but in achieving that goal we must ensure that adequate safeguards are in place to protect a rapidly changing environment that is subject to increasing stressors.

The Marine Mammal Commission’s Offshore Energy website provides information on the status of both conventional oil and gas and renewable energy development activities in U.S. federal waters, also referred to as the U.S. Outer Continental Shelf. The website also summarizes impacts associated with various stages of energy development, actions being taken to mitigate those impacts, and ongoing research and monitoring activities.

Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico

For additional information on offshore energy development and impacts on marine mammals, see the Commission’s 2010–2011 annual report and 2012 annual report.

The Marine Mammal Commission adheres to various policies and guidelines in fulfillment of its mission. This page includes information about the Commission’s various policies.

For more information about Equal Employment Opportunity (EEO), No Fear Act, and other related policies, click here.

The Marine Mammal Commission is committed to maintaining the integrity of, and promoting public trust in, the science used to inform policy decisions under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) and related statutes. The Commission has established and follows specific measures to meet its commitment to scientific integrity. The MMPA assigns seven major duties to the Commission (16 U.S.C. § 1402(a)), nearly all of which involve gathering, compiling, evaluating, analyzing, interpreting, and/or reporting scientific information. The Commission uses such scientific information to conduct specific reviews and studies, and to formulate recommendations to other agencies, the Administration, and Congress. To learn more, read the Commission’s scientific integrity policy document (to be updated).

The Marine Mammal Commission has adopted guidelines to ensure and maximize the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of information disseminated by the agency in accordance with the directive issued by the Office of Management and Budget (67 Fed. Reg. 8452B8460), pursuant to Section 515 of the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for FY 2001. To learn more, read the Commission’s guidelines for ensuring and maximizing the quality, objectivity, utility, and integrity of information.

In 1972, the MMPA established the Marine Mammal Commission to provide independent oversight of the marine mammal conservation policies and programs being carried out by federal regulatory agencies.

Harbor seals on ice. (NOAA Fisheries)

The Marine Mammal Commission provides independent, science-based oversight of domestic and international policies and actions of federal agencies addressing human impacts on marine mammals and their ecosystems. Our mission is largely driven by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). The MMPA was enacted in October 1972 in partial response to growing concerns among scientists and the general public that certain species and populations of marine mammals were in danger of extinction or depletion as a result of human activities. The MMPA set forth a national policy to prevent marine mammal species and population stocks from diminishing beyond the point at which they cease to be significant functioning elements of the ecosystems of which they are a part.

Our role is unique

We are the only U.S. government agency that provides comprehensive oversight of all science, policy, and management actions affecting marine mammals.

The Commission is charged with the following seven duties, as defined under section 202 of the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA):

In addition to the MMPA, other important legislation has been enacted to protect and conserve marine mammals and their ecosystems.

About the Commission: One-Page Infographic

To learn more about the Commission and our work, sign up for our e-newsletter and follow us on Twitter.