Polar Bear

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) listed the polar bear as a threatened species throughout its range in 2008 due to the threat of extinction posed by the loss of sea-ice as a result of climate change. Sea-ice constitutes essential polar bear habitat and provides the platform from which polar bears hunt their primary prey, ice seals. In 2016, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) updated an analysis of the threats posed to polar bears and concluded that range-wide persistence of polar bears will likely require stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of this century.

Female polar bear with cubs. (Ian Stirling)

Species Status

Abundance and Trends

Worldwide polar bear numbers are estimated to be around 23,000 animals (Hamilton and Derocher, 2018). Polar bears are distributed among 19 populations, two of which occur in U.S. waters: the Chukchi/Bering Seas population and the Southern Beaufort Sea population. Because polar bear habitat is vast and difficult to access, reliable abundance estimates are difficult to obtain. The best estimates of population size for the two U.S. populations are provided in the stock assessment reports prepared by FWS under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA). These reports estimate 2,000 bears in the Chukchi/Bering Seas population (based on extrapolated data that were collected in the 1990s) and 900 bears in the Southern Beaufort Sea population (based on a capture-recapture analysis from 2004 to 2010).

The International Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) in early 2015 found data deficiencies for the Chukchi/Bering Seas population, indicating that any abundance estimates and trend assessments are considered unreliable. In 2016, U.S. and Russian researchers conducted aerial surveys using thermal imaging to try to obtain an updated and more reliable population estimate of the Chukchi/Bering Seas polar bear population. This study, published in 2021, estimated the 2016 polar bear abundance in the Chukchi Sea to be between 3,435 and 5,444 bears. A separate study published in 2018 estimated that the average abundance of this population from 2008 to 2015 was approximately 2,900 bears.

A study published in 2020 estimated the abundance of the Southern Beaufort Sea population at 1,300 bears in 2003, a decline to 525 bears in 2006, and then relative stability between 2006 and 2015, with an estimated 573 bears in 2015. These trends and abundance estimates were also supported by a study published in 2021. New modeling methods, that incorporate resource selection, are currently being developed to help reduce the uncertainty associated with polar bear abundance estimates. In addition, a joint effort between the U.S. and Canada is working to produce a new population-wide abundance estimate.

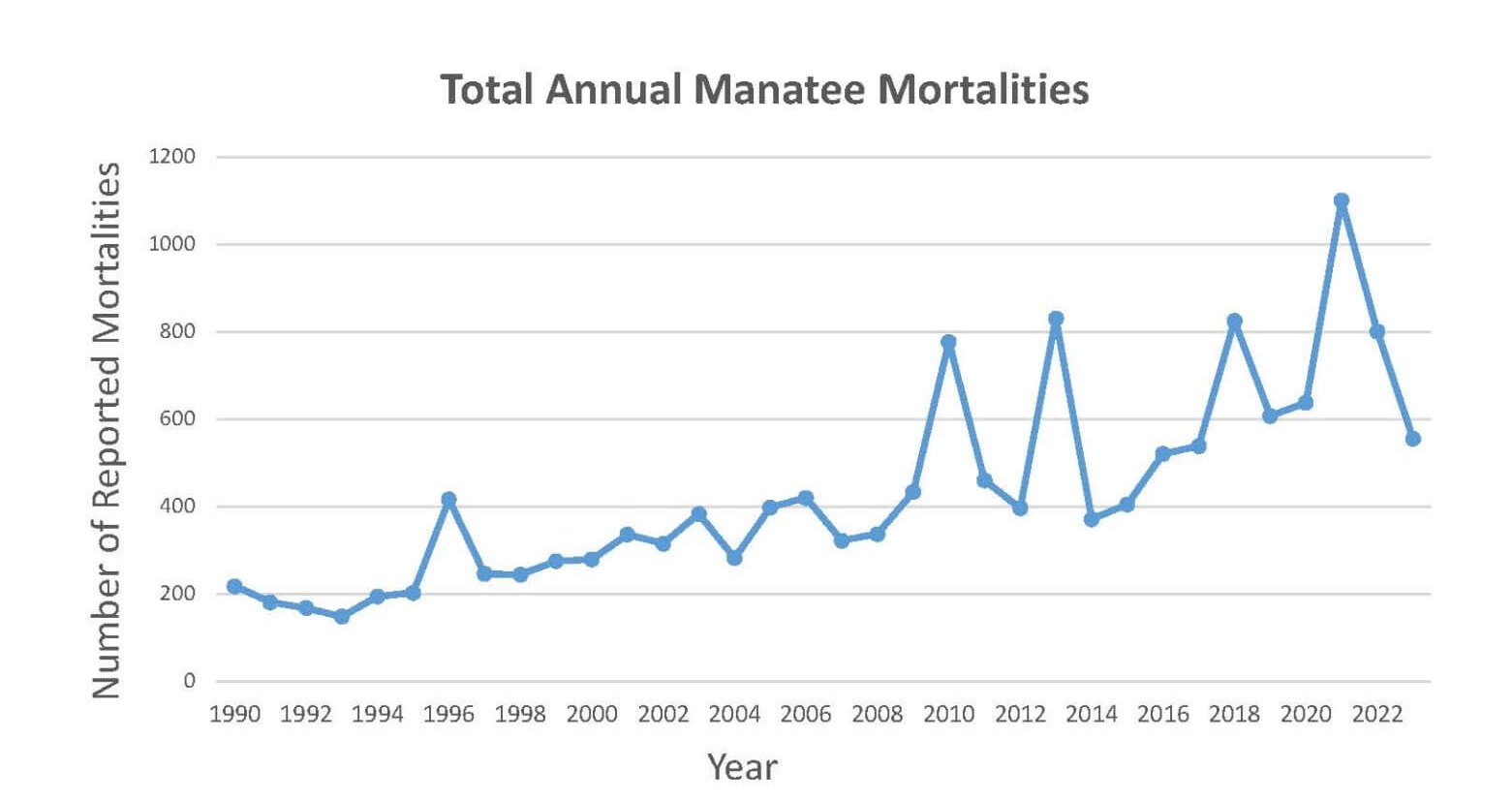

Population trends for the 19 recognized populations of polar bears. (NOAA Climate.gov)

Distribution

Polar bears inhabit the circumpolar Arctic and portions of the subarctic on sea-ice and along coastal areas and islands. Although they sometimes range into international waters, polar bears generally occur in areas under the jurisdiction of five countries: Canada, Greenland (Denmark), Norway, Russia, and the United States (Alaska). Scientists and managers recognize 19 relatively discrete subpopulations, two of which occur in the United States. The Chukchi/Bering Seas population is shared with Russia and the southern Beaufort Sea is shared with Canada.

Cooperative Conservation Efforts

As a party to the 1973 Agreement on the Conservation of Polar Bears, the United States works internationally to pursue the conservation of polar bears and their habitat. The five “Range States” that are parties to the agreement (Canada, Denmark (Greenland), Norway, Russia, and the United States) met in Greenland in September 2015 to discuss a variety of research and management issues. At that meeting, the Range States adopted a circumpolar conservation plan for the species and a two-year implementation schedule. In 2020, the Polar Bear Range States reviewed their progress in achieving their conservation objectives and created a more detailed implementation plan for 2020-2023.

Under a bilateral agreement between the United States and Russia regarding the shared Chukchi/Bering Seas population, the two countries jointly manage this population, including the adoption of annual sustainable harvest limits. At its 2016 meeting the U.S.-Russia Polar Bear Commission agreed to retain the previously adopted annual harvest limit of 58 bears, and in 2018, increased the limit to 85 bears, no more than one-third of which can be female.

In early 2017, the Indigenous People’s Council for Marine Mammals (IPCoMM) convened a meeting of village representatives concerning the establishment of a new Alaska Native organization to engage in co-management of polar bears. Subsequent meetings culminated in the formation of a new organization, the Alaska Nannut Co-Management Council (ANCC), which has been recognized by the FWS as the successor entity to the Alaska Nanuuq Commission under section 501(2) of the MMPA. The council consists of members from 15 tribes that have traditionally harvested polar bears for subsistence. Currently, the ANCC is working with the FWS and local communities to develop a harvest management plan.

What the Commission Is Doing

The Marine Mammal Commission is working closely with the FWS to promote the conservation of polar bears. The Commission participates on U.S. delegations to international polar bear meetings and participated on the polar bear recovery team that developed the Polar Bear Conservation Management Plan. In those capacities, the Commission is integrally involved in advising the FWS and others on conservation needs and priorities for the species and on steps needed to meet U.S. obligations under the two applicable international agreements.

Polar Bear Summit

In coordination with FWS, the Alaskan Nanuuq Commission, Kawerak, and the North Slope Borough, the Commission co-convened a summit on June 1-2, 2016 in Nome, AK, to promote the co-management of polar bears for subsistence use, especially in relation to the agreement with Russia on the conservation and management of the Alaska-Chukotka stock. This meeting allowed federal managers and Alaska Natives to consider options available for implementing U.S. responsibilities under the agreement and provided useful background for the ongoing efforts to form a new Alaska Native organization for polar bears.

Comments on Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking

On 9 January 2017, the Commission provided comments to the Fish and Wildlife Service in response to an advance notice of proposed rulemaking seeking input on developing a regulatory program and local management structures to carry out U.S. responsibilities under the United States-Russia Polar Bear Agreement and Title V of the MMPA. The Commission noted that the expectation has always been that U.S. implementation of the agreement would be achieved jointly by the FWS and an Alaska Native partner and that this continues to be the preferred path. The Commission also believed that it should be left largely to the Alaska Native communities to decide how they want to be represented. The Commission supported the adoption of regulations that recognize shared management and enforcement responsibilities and suggested two alternatives for providing the new Alaska Native organization with the necessary legal authority to carry out those functions.

Commission Reports and Publications

For historic information about polar bears and Commission-related activities, see our 2012 annual report.

Commission Letters

| Letter Date | Letter Description |

|---|---|

| April 2, 2025 | |

| September 20, 2017 | |

| January 9, 2017 | |

| July 11, 2016 | |

| October 16, 2015 | Letter to FWS regarding the draft polar bear conservation management plan |

| February 8, 2013 | |

| August 3, 2012 | Letter to FWS regarding a proposed rule that would re-instate the special rule for polar bears |

| June 20, 2012 |

Learn More

Threats

The primary threat to the polar bear is the predicted loss of sea-ice and associated prey base. Other potential threats include oil spills and contaminants, unsustainable removals (e.g., in defense of life or for subsistence), loss of denning habitat, disease, and disturbance from increasing activities in the Arctic. Polar bears are increasingly summering on land in response to sea-ice loss, and models estimate that 80-100 percent of polar bears in the Chukchi Sea and 61-97 percent of bears in the southern Beaufort Sea will spend more than 3 weeks on land by 2065. Recent research efforts by the USGS have assessed how sea-ice loss and altered habitat use affect polar bear home range size, exposure to pathogens and contaminants, body condition, and reproduction.

Current Conservation Efforts

Due primarily to the predicted loss of sea-ice in Arctic waters over the coming decades, the FWS listed the polar bear as a threatened species in 2008. The FWS designated much of the area inhabited by polar bears in Alaska as critical habitat in 2010. That designation, vacated in 2013 by the U.S. District Court in Alaska, was reinstated by a 29 February 2016 ruling of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The Endangered Species Act requires that the FWS develop a recovery plan for listed species, including the polar bear. The FWS published its Polar Bear Conservation Management Plan on 20 December 2016 to meet that requirement and to serve as a conservation plan under the MMPA. The plan concluded that range-wide persistence of polar bears will likely require stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions by the middle of this century. Other threats to polar bears were found to be mostly insignificant compared to the risk of extinction posed by climate change and the associated loss of sea ice.

In addition, the five polar bear range states developed a circumpolar action plan for polar bears in 2015, drawing on each country’s national plan. This 10-year plan aims to strengthen range-wide polar bear conservation efforts.

In 2023, FWS completed a 5-year status review and determined that the polar bear should maintain its classification as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. In the review, sea ice decline was again identified as the primary stressor affecting all aspects of polar bear life history and threatening polar bear persistence and recovery.

The Commission will continue to play an active role in advising the FWS and others on polar bear conservation matters. The Commission also will continue to play an oversight role regarding implementation of U.S. obligations under the applicable international agreements.