A Spotlight on Marine Mammals in the Hawaiian Islands and the Wider Pacific

The Marine Mammal Commission’s 2019 Annual Meeting (held May 21–23, 2019, in Kona, Hawai‘i) focused on marine mammal science and management issues in the Hawaiian Islands and the wider Pacific region. The meeting included presentations on the region’s physical and biological characteristics.

Participants discussed the status and population trends of several key species, reviewing threats and actions to address them, learning about innovative techniques for monitoring marine mammals, and considering management and policy recommendations. The presentations are summarized below. To see the full conference proceedings, including complete presentations, go to the 2019 Annual Meeting page. Scroll down for more on the 2019 Meeting!

NOTE: Most of the information presented here represents the state of knowledge at the time of our 2019 annual meeting. For updated information, see the links at the bottom of this page.

(NOAA Permit #14682-38079)

(NOAA/PIFSC/HMSRP)

Overview of the Hawaiian Islands

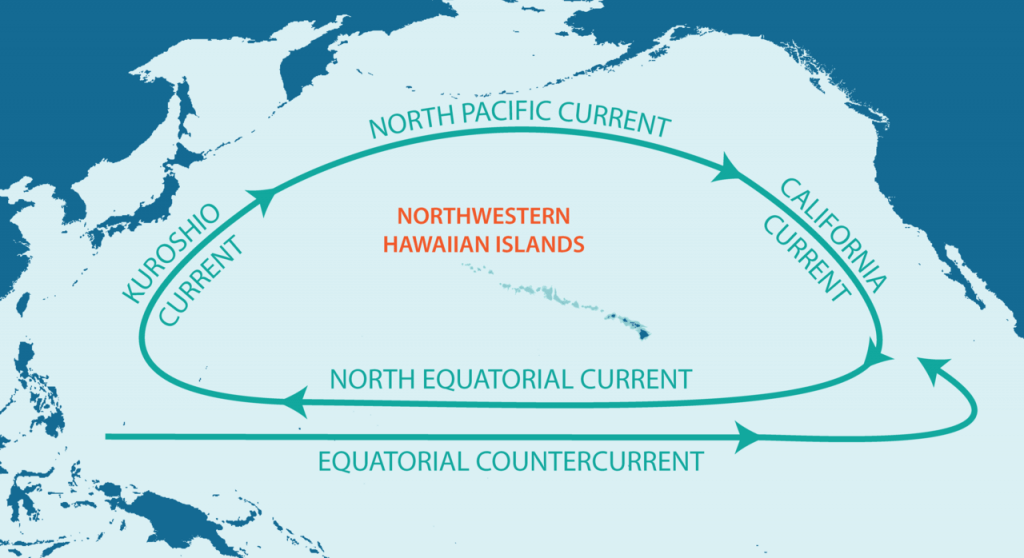

One major oceanographic feature affecting the marine environment of the Hawaiian Islands is the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Hawai‘i sits at the center of this gyre’s warm waters. The gyre is vertically stratified, which means nutrients are weakly mixed up to the surface, resulting in low surface chlorophyll levels.

It may seem surprising that a region of relatively low biological productivity would be home to many large marine species. At least 25 marine mammal species are known to inhabit these waters, including both pelagic (offshore) and insular (island-associated) populations. These species and their prey are supported by oceanographic features, like fronts and eddies, and topographic features, such as banks and sea mounts. These physical attributes of the surrounding ocean create nutrient-rich hotspots that support a diverse food web. From microscopic phytoplankton to sperm whales, many species thrive in these subtropical waters.

The ecosystem in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is heavily impacted by human activity:

- Commercial fisheries change the ecosystem’s trophic structure and species composition. For example, longline fishing around the Hawaiian Islands can determine which species flourish and which do not. When fisheries remove large percentages of predatory fish (like tuna) from the food chain, smaller fish populations increase. This could have potential effects on ecosystem biodiversity and resilience.

- Climate change affects this ecosystem in multiple ways. Warming ocean temperatures could alter ocean circulation patterns, affect the timing of spawning and feeding events, lead to changes in species distribution, and result in coral bleaching events. Ocean acidification could further impact corals. Sea level rise is already impacting the low-lying islands and atolls in the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, resulting in loss of habitat that is essential to numerous seabird, sea turtle, marine mammal, and endemic terrestrial species.

- Marine debris, including lost and abandoned fishing nets and gear, gets caught in the gyre’s currents and is transported to the Hawaiian Islands from all over the Pacific. Marine debris not only litters the region’s ocean and coastlines, but it poses a serious choking and entanglement hazard to seabirds, sea turtles, Hawaiian monk seals, and cetaceans. Derelict fishing gear also severely damages the structure of fragile coral reef ecosystems.

Wider Pacific Islands Region

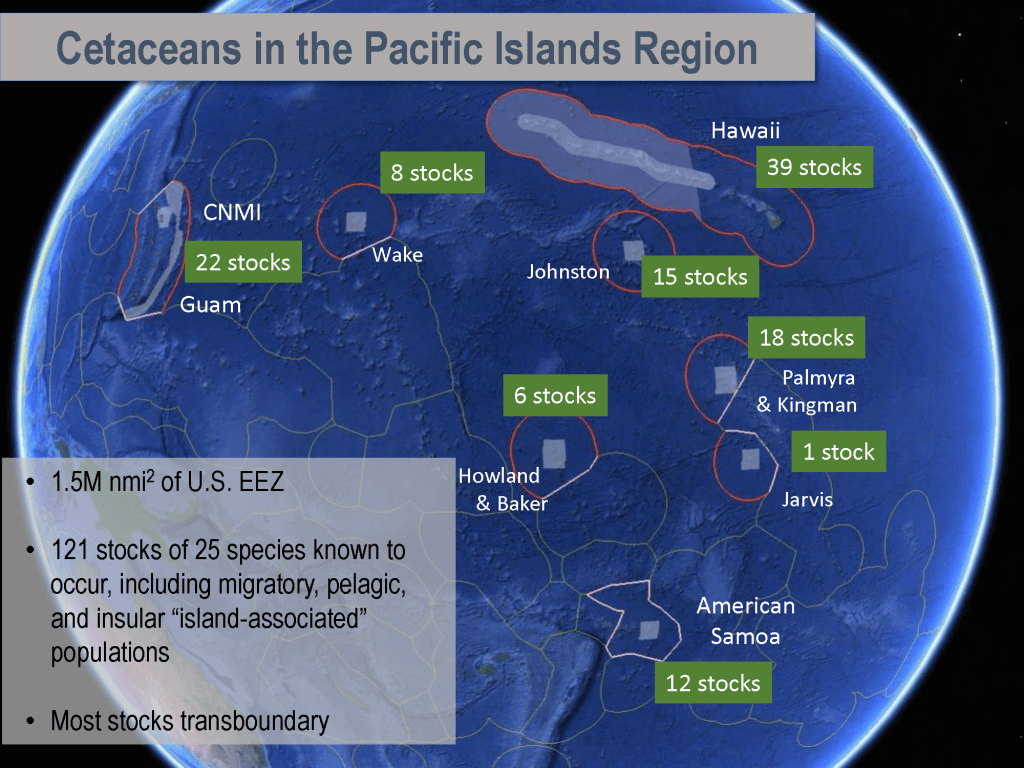

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is responsible for managing marine mammals over a huge area in the Pacific Islands Region, about two million square miles (roughly half the size of Europe)! Little is known about many of the 121 stocks, or populations, of the 25 marine mammal species in the waters around the U.S. Pacific Island territories, including Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. However, efforts are underway to improve our understanding of whale and dolphin populations in this region.

The size of this area, coupled with the high mobility of marine mammals, make it difficult to collect data on the species and stocks; we have no data on over half of the stocks in the region. To address this, NMFS has teamed up with other government agencies with similar research objectives in the Pacific. This multi-agency effort to assess whale and dolphin populations, known as PacMAPPS, will include vessel-based research surveys of the Mariana Archipelago in 2021, with additional surveys through 2022. PacMAPPS utilizes visual, passive-acoustic, and photographic data to assess marine mammal abundance and distribution in the surveyed areas.

In addition to the vessel-based, multi-agency research surveys, scientists and managers depend upon creative solutions and advanced technologies to gain information on marine mammals in the Pacific Islands Region. Using passive acoustic monitoring (PAM), from unmanned underwater listening stations, scientists can learn about the presence of whales and dolphins in remote locations from their sounds, in areas and seasons inaccessible to live observers.

Collaboration with local partners is essential to improving our understanding of marine mammals in the Pacific Islands Region. Building capacity in remote areas of the Pacific can enhance marine mammal stranding (when an animal washes ashore) response and research efforts, strengthening our ability to mitigate threats from human interaction, disease, and marine debris ingestion.

Spinner Dolphins

Spinner dolphins are abundant in the Hawaiian Islands. Five spinner dolphin populations live around the islands—one pelagic population and four insular populations. The pelagic stock is largely unstudied, and we know relatively little about the abundance of the insular stocks, although recent abundance surveys estimated the minimum population size of the Hawai’i Island stock to be 665 animals.

While there have been several cases of disease and entanglement documented in spinner dolphins around the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI), the main threat to spinner dolphins in Hawai’i is harassment by boaters and swimmers that disrupts dolphin resting behavior. Dolphin watching tours typically occur in the daytime, when dolphins return to nearshore bays to rest. This heightened vessel activity and associated interactions between people and resting dolphins may be affecting the health of individual animals as well as the overall populations. Over time, repeated disturbance may cause animals to abandon resting areas or to fail to recover from daily foraging trips, ultimately compromising their foraging and anti-predator behaviors and reducing their reproductive success.

The National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) is working to help protect spinner dolphins by:

- Developing regulations to reduce the harassment of spinner dolphins by prohibiting vessels and swimmers from approaching dolphins closer than 50 yards, and prohibiting vessels and swimmers from intercepting the path of dolphins

- Increasing engagement with the community and tour operators to promote voluntary measures to decrease the harassment of spinner dolphins

- Building partnerships with the tourism industry in Hawai‘i and working with local organizations, like the Friends of Ho‘okena Beach Park, a local nonprofit, to help develop dolphin viewing signage and conduct outreach with tourists

- Increasing federal enforcement activities related to spinner dolphin harassment by following up on reports of harassment of dolphins (many submitted through social media) and supporting state enforcement efforts

To address data gaps in stock abundance estimates and assess the effects of direct and indirect threats to the overall health of populations, NMFS’ Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center began to undertake four priority projects beginning in 2020:

- Conducting line-transect vessel abundance surveys around Hawai‘i Island, O‘ahu, and Maui Nui (Maui, Lāna‘i, Moloka‘i, Kaho‘olawe)

- Providing new abundance estimates for the Kona coast, based on capture-mark-recapture techniques (i.e., photo-identification studies)

- Using unmanned aircraft systems (UAS)–based photogrammetry to assess population age structure

- Supporting passive acoustic monitoring around the MHI to inform abundance estimates and examine spinner dolphin occurrence and resting patterns before and after a rule is implemented

Hawaiian Monk Seals

The Hawaiian monk seal is the most endangered pinniped in U.S. waters and one of the most endangered seals worldwide. Most Hawaiian monk seals live in the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI), where their numbers declined by more than 70% after the 1950s. Fortunately, since 2013, the population has been slowly increasing. Still, seals in the NWHI face serious threats, including food limitation, entanglement in marine debris, shark predation, and terrestrial habitat loss due to climate change.

Since at least the 1990s, a small population in the main Hawaiian Islands (MHI) has increased significantly in size and now represents 20% of the species’ total population. A recent study classified causes of death of MHI monk seals as natural, anthropogenic, and disease. The study revealed that the top two direct anthropogenic causes of death for monk seals were trauma (including intentional killing) and drowning in fishing nets, so reducing the number of human-caused deaths from trauma and drowning would have a large positive impact on monk seal population growth in the MHI.

Hawaiian monk seals may drown when they become entangled in gill nets. Hawaiian state legislators have introduced a bill that, among other things, would shorten the amount of time nets can be left unattended in the water. It would also change the registration process to make it easier to identify and cite someone illegally using these nets.

Infectious diseases are also a threat to monk seals:

Morbillivirus is a genus of viruses that can cause disease in many animals. Viruses in this group can cause measles in humans and distemper in dogs and seals. Distemper viruses have caused mass die-offs of many thousands of seals in other parts of the world. While morbillivirus has not yet been detected in monk seals, the potential catastrophic effects should an outbreak occur motivated NOAA to implement a preventative vaccination program to protect the species from potential future outbreaks.

Toxoplasmosis is a disease caused by a protozoal parasite (Toxoplasma gondii), which has a complex life cycle requiring cats as hosts for production of eggs. An infected cat produces millions of eggs which are passed through the cat’s feces into the environment and find their way into the ocean. Toxoplasmosis is lethal to infected monk seals, causing a slow and extremely painful death. There is no vaccine available to prevent infection nor any known treatment. Toxoplasmosis impedes monk seal population growth in the MHI to the same degree as human-caused trauma and net drownings. The threat of toxoplasmosis is primarily in the MHI, where people have introduced domestic and feral cats, which now number at least several hundred thousand. However, the parasite’s eggs are extremely hardy and could potentially be transported to the NWHI and infect seals there. Click here for more information on Toxoplasmosis.

Pelagic False Killer Whales

Pelagic false killer whales are found in the deep oceanic waters around the Hawaiian Islands. The number of false killer whales in this population has declined in recent decades, likely due to interactions with fisheries, including longlines, a type of fishing gear which consists of a mainline, several miles in length, and thousands of branch lines with baited hooks. Pelagic false killer whales regularly take bait or fish off longline hooks and are occasionally hooked, sometimes fatally. Changes in how false killer whales are surveyed have improved the precision of abundance estimates, but have made it very difficult for scientists to detect trends in population size. In recent years (2014-2019), an estimated 40 whales per year have died or been seriously injured and assumed to have died in the longline fishery. Outside the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), the number dying during those six years was over three times greater than during the previous six-year period (2008-2013). Inside the EEZ, bycatch rates had been declining following the implementation of mitigation measures, but that trend has reversed and the number estimated to have died increased rapidly from roughly 4 per year from 2014-2016, to 15 per year from 2017-2019.

Mitigation of this bycatch problem is the focus of NMFS’s False Killer Whale Take Reduction Team, a diverse stakeholder group that provides management recommendations to NMFS, and which includes a Commission representative. A take reduction plan implemented in 2013 aimed to reduce the number of deaths and serious injuries of pelagic false killer whales by requiring fishermen to use relatively weak hooks and strong branch lines. This gear configuration was designed to cause the hook to straighten when tension is applied, thus releasing a hooked whale hopefully with minor injuries.

Unfortunately, after five years of the fleet using this particular gear and handling configuration, only 10 percent of the hooks involved in false killer whale interactions straightened as designed. The Take Reduction Team is currently discussing whether to require even stronger lines and weaker hooks, and is increasing efforts to better train fishermen in proper handling techniques. The team is also considering the deployment of electronic monitoring systems on longline vessels to monitor false killer whale handling performance by vessel captains and crews.

While many researchers believe weakened hooks and better training are achievable solutions to the whale bycatch problem, others are concerned that they are not. Even though there is no easy way to mitigate vessel and pelagic false killer whale interactions, it’s important for the U.S. fleet to have strong and effective measures. The bycatch reduction measures adopted in the United States could inform and guide international bycatch-reduction efforts. Solutions that work for the Hawaiian fleet could be shared and hopefully lessen interactions between marine mammals and longline fisheries around the world.

Inshore Toothed Whales of the Hawaiian Islands

Nearshore hook-and-line fisheries and the island-associated populations of several odontocete species (dolphins and toothed whales) often come into contact with one another. Island-associated toothed whales include pantropical spotted dolphins, rough-toothed dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, and insular false killer whales. Since the State of Hawai‘i does not actively monitor nearshore hook-and-line fisheries (e.g., trolling, shortline, and handline), researchers have little direct evidence of interactions between fisheries and insular odontocetes. Most evidence comes from indirect sources, including interactions reported by fishermen, gear found on carcasses recovered onshore, and gear seen on live animals at sea.

Extensive observations by biologist Robin Baird, a scientific advisor to the Commission, and his colleagues have documented injuries and scars on several species, including pelagic false killer whales and pygmy killer whales, consistent with fishing line interactions. Most of these interactions likely occur when bait or catch on hooks is taken as food. Certain fishing practices, unfortunately, encourage these interactions. For example, fishermen off Kona commonly use spotted dolphins as a cue to the presence of their target species and have been documented trolling through and around groups of these dolphins off Kona.

The State of Hawai’i’s Department of Land and Natural Resources is gathering data on interactions with vessels and fisheries. The state requires commercial fishermen to submit reports with information on marine mammal depredation and bycatch events voluntarily, but recreational fishermen do not have the same reporting requirements. To mitigate harmful interactions with fishermen, the state is working to conduct outreach to educate them on best practices.

Insular false killer whales are similar to pelagic false killer whales, except that they live in nearshore waters rather than the open ocean. Two stocks of insular false killer whales live around the Hawaiian Islands:

- The population of insular false killer whales that lives exclusively in MHI nearshore waters is considered the primary stock. This MHI population has fewer than 170 individuals; this reduced population size is likely due to interactions with fisheries.

- Another stock of unknown size occurs around the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

According to Baird’s research, the greatest potential for interaction between nearshore hook-and-line fisheries and false killer whales occurs off the northern tip of the island of Hawaiʻi and off the northern sides of Molokaʻi and Maui. NMFS developed a detailed recovery plan for the endangered insular false killer whale population in 2020 that includes targets to stabilize the population and goals to remove threats to its viability. The Commission provided comments and recommendations on the plan in its 18 December 2020 letter.

Humpback Whales

Humpback whales are the most common whale species in the waters around the Hawaiian Islands. Humpback whales in Hawai‘i are part of the Central North Pacific stock, one of three stocks of humpback whales in the North Pacific Ocean listed as depleted under the Marine Mammal Protection Act.

(NMFS Permit #782-1719)

(HIHWNMS/ NOAA Permit # 20311)

The Hawai‘i segment of the Central North Pacific stock spends the winter and early spring in Hawaiian waters (primarily off Maui) and then migrates north to feed, primarily in waters off northern British Columbia and southeast Alaska. A sudden and dramatic decline in sightings of known individuals and mother-calf pairs was reported starting in 2013 in southeast Alaska and Prince William Sound by the Glacier Bay National Park, the Survey of Population Level Indices for Southeast Alaskan Humpbacks, and Gulf Watch Alaska. These groups also reported sightings of abnormally thin whales and unusual skin conditions. Similar declines in whale numbers and mother-calf pairs were subsequently reported offshore of Maui in 2015. Preliminary data from recent studies indicate that encounter rates in Hawai’i may have returned to pre-2015 levels.

Currently, researchers are prioritizing studies that:

- Investigate where whales are going to breed and feed

- Assess body condition

- Determine whether reproductive rates, abundance, and survival have changed over time

- Identify possible changes in food resources that could be associated with ocean heat events

- Investigate the role of anthropogenic and environmental factors in any observed changes

Researchers are using new technologies, like unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) and underwater wave gliders, to monitor humpback whale abundance, body condition, and movements around Hawai‘i and across the Pacific. Scientists use UAS images to obtain whale length and width measurements in studies of body condition to monitor the health of both individual humpback whales and the overall population. UAS can also provide data on scarring to help identify signs of entanglement or vessel strikes. Underwater wave gliders can be used to acoustically detect whales at a lower cost and in areas and seasons when visual, vessel-based surveys are not possible.

In addition to climate change, major threats to humpback whales include entanglement in fishing gear and interactions with vessels. The most common gear found on both stranded and swimming whales is crab pot/trap gear, primarily from Alaska and British Columbia. In addition, there has been a five-fold increase in small vessel traffic in humpback whale habitat off Maui since the 1980s. Regulations to protect humpback whales from close approaches (within 300 meters) of whale-watching and other vessels within 200 meters of shore have been in place since 1987 and were revised in 2016 to maintain many of the same restrictions, now under authority of the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Most violations are reported through social media because on-water law enforcement presence is limited. Instead, the focus is on strong outreach and education, with an emphasis on educating news media not to glamorize close encounters with humpback whales.

(OPR / NMFS PIRO)

NOTE: Most of the information presented here represents the state of knowledge at the time of our 2019 annual meeting. For updated information on some of the topics discussed, please visit the websites below or email a member of the Commission Staff:

Scrolling Photo/Video Credits:

- Overview of the Hawaiian Islands: Presentation by Erin Oleson, NOAA/PIFSC

- Wider Pacific Islands Region: Cascadia Research Collective, NMFS Permit #20605

- Spinner Dolphins: Marine Mammal Research Program, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, NOAA Permit #21476

- Hawaiian Monk Seals: Fabien Vivier, provided by Marine Mammal Research Program, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

- Pelagic False Killer Whales: Cascadia Research Collective, NMFS Permit #20605

- Inshore Toothed Whales of the Hawaiian Islands: Marine Mammal Research Program, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, NOAA Permit #21476

- Humpback Whales: Marine Mammal Research Program, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, NOAA Permit #21476